The Inheritance of Diligencias

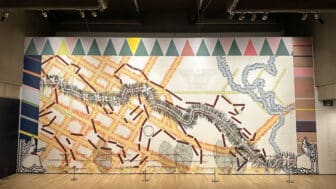

Each day we traverse spaces that might not immediately stand out as especially important, but which ground us in place, time, and community. The street corners, storefronts, or restaurant awnings that we pass by accumulate as part of our personal histories, as well as those of the neighborhoods we inhabit. Lucia Hierro’s large-scale vinyl and paint installation Diligencia (2021) records many of these histories and changes, whether through gentrification or demographic shifts, of the neighborhoods that she herself is a part of in Upper Manhattan and the Bronx. Diligencia also offers an opportunity to consider the evolving, continual, and deracinating disruptions undergone by aging immigrant populations.

I grew up in Washington Heights and Inwood and make regular visits back to see family there, and Hierro’s installation brings to mind the sites, objects, and memories of my upbringing. As a photography historian, part of my academic training has been studying how we remember. More recently, prompted by a family member’s dementia diagnosis, my focus has increasingly turned to how, what, and when we forget. Witnessing how memories are built and lost within minutes, possibly retrieved later or never again, is part of a new routine accompanied by an unfamiliar vocabulary scattered across neurological testing results. With age, and especially when coupled with dementia, forgetting the date or who is president is one thing. How, though, do other disappearing memories of daily existence as related to place, people, and home lead to lost local and personal histories? Bridging these different positionalities is at the core of how I come to Hierro’s artwork, one that in and of itself is an attempt at preserving histories.

Diligencia is an almost life-scale mural-like installation depicting a grocery store cart with toys, the storefront of an “international multiservice” business, a folding personal shopping cart, a garbage can, a newspaper dispenser, music posters, and awnings for remittance businesses. Each of these elements is potentially recognizable to those encountering Hierro’s work for the first time. They are the storefronts and street accoutrements commonly found in many parts of Upper Manhattan and the South Bronx, as well as other immigrant neighborhoods across the United States. The international multiservice business Mundito (small world) has the specificity of an address. This detail, 200 Dyckman Street, invites us to search for its exact location, which is at the intersection with Vermilyea Avenue, at a border between Washington Heights and Inwood. The storefronts and the objects on their own contain munditos within them, as do the people Hierro has removed from the composition.

detail of shopping cart.

Although the likenesses of individuals are absent from Hierro’s work, they remain present through the imprints of their existence on Dyckman Street and elsewhere. In fact, Hierro often starts with photographing the people, places, and objects around her, extracting details that later envelop us in a version of the worlds that she travels through. 1 In part, Hierro does not include the people from her original photographs to protect their privacy. Their likenesses would also distract from her project, yet their lives remain essential to its success. Hierro is aware of the people who live and work in the neighborhoods, and connects with initially reticent vendors who acquiesce to having their carts photographed. Though they remain absent, through her artworks, Hierro reminds us that “people live here.” 2

The very storefront at 200 Dyckman Street is one of several businesses in Washington Heights and Inwood that caters to the area’s predominantly Dominican population. Dominican immigration to New York City started in earnest in the early 1960s, by which time there were approximately 15,000 Dominicans in the United States. 3 As of the 2020 census, there were more than 700,000 members of New York City’s Dominican community. 4 Upper Manhattan, parts of which are called “Little Dominican Republic,” continues to be an enclave and magnet for the Dominican diaspora as well as to newcomers from other Latin American countries. The services rendered at Mundito range from remittances and the delivery of boxes, mainly to the Dominican Republic, but also worldwide, as well as basic photocopying and document printing. 5 There are indeed munditos within this business and many others like it, that serve as intermediaries between the United States and the countries of origin for many who utilize their services. For those who enter these businesses, each of the services is also a responsibility, and often the well-being of those on the receiving end, of all generations, is at stake.

Hierro’s Diligencia focuses on a space and word that for some implies urgency and obligation. Within the context of Dominican Spanish as spoken by Hierro’s family, and mine, diligencia is not simply an errand. It conveys something almost official that must happen—picking up a prescription, going to a travel agency, or, as Hierro alludes to through her selection of this business, sending money and packages back home. Missing any diligencia might unravel the delicate and sometimes tenuous balance of life for those in many immigrant communities and the people who depend on them in their home countries. As Hierro and I recently reminisced about our upbringings, each of us could name moments when our elders urgently needed us to conduct a diligencia. 6 In some cases, conflicting schedules governed this transfer of duty. In others, knowledge of English was often key to resolving whatever task was at hand. These duties might rise beyond the quotidian, and for the elders, the eventual loss of control over these diligencias can be especially destabilizing. In their transfer from one generation to the next, diligencias gain or lose importance, at times becoming even more pressing for those who inherit them.

Hierro has noted that she has an urge to “record keep,” perhaps an inheritance of her own. 7 This recordkeeping, in turn, brings us into a space of documentation and the formation of histories of a place and its people. As the address in this artwork denotes, the specificity of place is critical to Hierro. Place is likewise important to migration and memory, as the cultural memory historian Julia Creet reminds us. Though there has been a continual urge to focus on what has been left behind, rather than what stands before migrants in their new environments, Creet proposes a perspectival shift in which “[memory] is where we have arrived rather than where we have left.” 8 This formulation opens the door to memory formation in a new place, as well as to the possibility of building new histories. Yet, there is a built-in instability to these memories and potential histories, as unstable as their new environments.

Migration is not a singular moment. It continues over time, prompting immigrant populations to be part of a perpetual state of adjustment. Their new neighborhoods also change, as do the members of these populations. 9 What is the impact on the individuals—who have grown familiar with these street corners and storefronts—as they themselves start to forget? How are their histories preserved, if at all? In focusing on these businesses at a particular time, in specific if separate neighborhoods, Hierro’s Diligencia centers a state of untethering and, ultimately, forgetting that is part of how a place and its people age. 10

In the end, we seem to be left just with things—fidget toys on a shopping cart, Target bags precariously placed in another cart, and the traces of business transactions. “When it becomes about consumption,” Hierro explains, “it becomes about all of us and our connections to objects and spaces.” 11 People might recognize a stand-up shopping cart, either from using one themselves or as a curious alternative to carrying bags. For some, a Target bag may elicit feelings of access to goods, whereas for others it may be a threat to their livelihood with larger stores supplanting microeconomies. These “connections to objects and spaces” are capacious and hold within them munditos of interconnected lives and livelihoods, and of consumption, but also of production, of networks that extend across borders and socioeconomic strata.

I wish to end by centering Hierro’s intent to nurture a practice that “really serves as a way to record keep” akin to oral histories. 12 “There are a lot of things that are lost, a lot of details that are lost, but in essence the thing still remains,” she explains.13 In this passage of information from one generation to the next, the individual photographs that Hierro takes and then rearranges in her compositions provide one part of this game of telephone, one part of the story. There may be a loss of detail and specificity, rendering Diligencia at once familiar and disorienting. In this tension, Diligencia is much like the memories that we forget, try to recall, or rebuild each day, and the histories that rest within them.

- Lucia Hierro, in conversation with the author, August 13, 2024. ↩︎

- Lucia Hierro, in conversation with the author, August 13, 2024. ↩︎

- Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, A Tale of Two Cities: Santo Domingo and New York after 1950 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 70–80. ↩︎

- NYC Planning Population FactFinder, “Population FactFinder, accessed January 23, 2025, https://popfactfinder.planning.nyc.gov/explorer/cities/New%20York%20City?censusTopics=detailedRaceAndEthnicity. ↩︎

- On the impact of remittances on sending populations in Washington Heights, see Shanny Spraus, “The Domestic Impact of International Remittances: The Role of Dominican Remittances in Washington Heights, New York” (Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, 2006). ↩︎

- Lucia Hierro, in conversation with the author, August 13, 2024. ↩︎

- Lucia Hierro, in conversation with the author, August 13, 2024. ↩︎

- Julia Creet, introduction to Memory and Migration: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Memory Studies, ed. Julia Creet and Andreas Kitzmann (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 6. ↩︎

- For a history of the area and neighborhood, some of the populations that have lived there, and some of the relationships among them, see Robert W. Snyder, “An Ordinary Neighborhood in an Extraordinary City,” in Crossing Broadway: Washington Heights and the Promise of New York City (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015), 11–44. ↩︎

- For recent literature on aging in Latinx populations and the diversity of aging experiences, see Katynka Z. Martínez and Mérida M. Rúa, special issue, “The Art of Latina and Latino Elderhood,” Latino Studies 19 (2021): 419–27. As of 2022, 19.6 percent of the population of Washington Heights/Inwood was sixty-five or older. See “Washington Heights/Inwood Neighborhood Profile,” NYU Furman Center, https://furmancenter.org/neighborhoods/view/washington-heights-inwood#demographics. ↩︎

- Lucia Hierro, in conversation with the author, August 13, 2024. ↩︎

- Lucia Hierro, in conversation with the author, August 13, 2024. ↩︎

- Lucia Hierro, in conversation with the author, August 13, 2024. ↩︎

Leslie Ureña’s research and museum work has focused on the history of photography, migration, and transnational art practices. Since 2023 she has been Associate Curator of Global Contemporary Art at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Prior to this role, she was Curator of Photographs at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

Cite this essay: Leslie Ureña, “The Inheritance of Diligencias,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, April 28, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/the-inheritance-of-diligencias/