Hilos and the Unraveling of Borders in the Work of Consuelo Jimenez Underwood

Consuelo Jimenez Underwood is a maestra de hilo (thread master) who uses her work to map a way back home for Xicanx peoples, who are descendants of Indigenous communities across Mesoamerica and the U.S. Southwest.1 Her work reckons with the complexity of borders, while revitalizing, reconnecting, and bringing forward Xicanx Indigenous knowledge, practices, and relationships to the earth. Like many U.S. Latinx people, Jimenez Underwood has experienced a lifetime of fragmentation caused by the creation of the U.S.–Mexico border. Although she was born in California, she grew up experiencing family separation because her father was born in Mexico.2 At an early age she was aware that the US–Mexico border was not natural and that it only served as a marker of the colonial project, which sought to erase Indigenous memory and bodies across time and space. Whether it is on a wall or a textile, the artist uses hilos to abolish borders. Her works Border Flowers Flag and Everything All at Once incorporate symbols that invite people to imagine a new idea of a world that extends beyond the confines of settler colonialism.

In 2008 Jimenez Underwood created Border Flowers Flag, a Xicana political iconoclastic take on the U.S. flag. For her, a flag that represents “America” comes in a triangular shape and is created from multiple fabrics. The silhouette of her flag is inspired by the row of flagpoles behind Barack Obama during his acceptance speech after winning the 2008 election.3 During the speech, the U.S. flags draped as a triangular shape instead of a rectangle. This inspired Jimenez Underwood to reflect on her own tricultural experience as a Xicana-Indigenous woman living in the U.S, whose identity does not fit into the demarcated American rectangular box.

Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California.

Jimenez Underwood’s triangular flag is composed of white Yaqui embroidered cloths; silkscreened over dyed kitchen towels; and gold silk fabric. The white Yaqui cloth comes from her husband’s ancestral homelands, and the towels are from her own kitchen. The repurposed towels and Yaqui fabric are used to create the stripes in the flag and pay tribute to the matriarchs who have spent a lifetime in their kitchens defying borders by “holding on to their Indigenous recipes and by creating new recipes through the blending of cultures through food.”4 The red- and blue-dyed towels have tonal interest from the resist of spots and drips of embedded oils and the deeper hues of underlying spice stains that register the textiles’ past in the artist’s kitchen. These stains stand in for the invisible labor that occurs in the kitchen and the machismo ideologies that confined women to the home. Thus, the kitchen towels serve as a critique of traditional gender divisions created by settler-colonial institutions such as the church, which has often been used to normalize machismo.

The stars in the flag are replaced here with state flowers of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, the four states that have been environmentally affected by the creation of the US.–Mexico border.5 By embroidering the California poppy, blossom of the saguaro cactus, yucca flower, and bluebonnet, Jimenez Underwood is calling attention to the ongoing environmental damage that the border has created for vegetation and life across the borderlands. 6 Furthermore, the silver embroidered flowers pay tribute to the constellations and the guiding knowledge the celestial stars provide, the brightest of which helped guide enslaved peoples in the U.S. toward liberation.7 In making the border flowers present, Jimenez Underwood is also celebrating Indigenous medicines and their healing properties that continue to flourish.8

The red stripes in the flag show rows of flying butterflies. In Xicanx art, monarch butterflies have been used as a symbol to denote migration across North America.9 Here the mixed butterflies on Border Flowers Flag signifies the diverse Latina/o/x communities that have migrated to the US—the red stripes can be read as the “red road,” or camino rojo, which represents in many Indigenous cultures a way of life rooted in walking on this earth in a responsible and respectful way.10 With these red roads illuminated by their border-flower constellations, Jimenez Underwood has created a flag that does not center a citizenship based on geopolitical borders or documents, rather, her flag is a pledge to walk the land and all relations with respect.

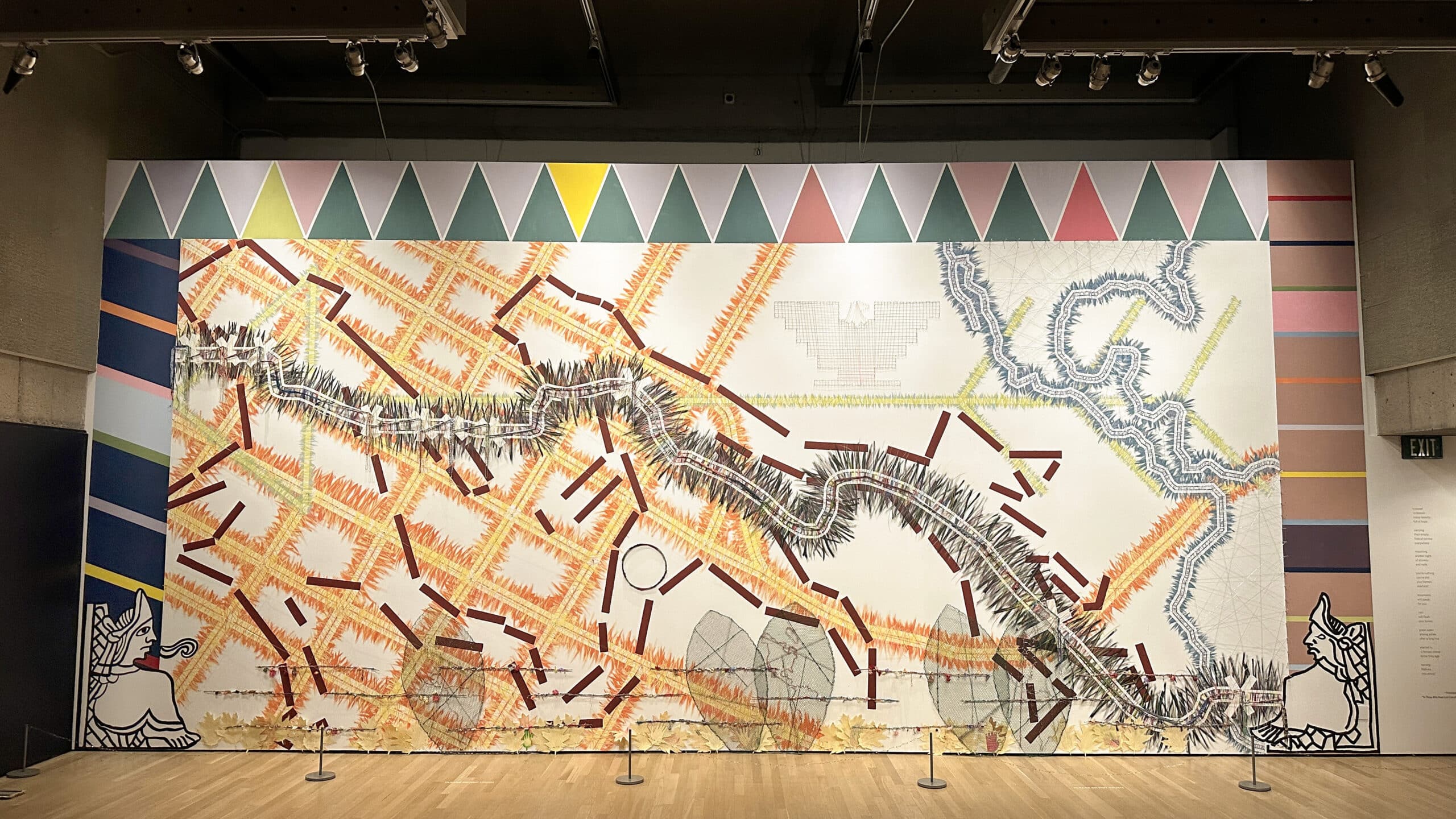

To unravel borders and bring awareness to the physical and metaphorical harm that the U.S.–Mexico border has created, Consuelo Jimenez Underwood also twills her hilos onto walls through her Borderline installations.11 Jimenez Underwood began her Borderline series in 2010, in the exhibition Bay Area Xicana: Spiritual Reflections/Reflexiones Espirituales at the Triton Museum of Art in Santa Clara, California, as a way to underline the ideological criminalization of the people and the natural world of the borderlands. 12 In 2024 she created Everything All at Once, an Oakland site-specific installation that wove together the experience and memory of Xicanx peoples across the past, present, and future. 13 The installation opened with two representations of Mesoamerican ancestors communicating to one another across the wall with speech scrolls coming out of their mouths to deliver a sacred message. Between them, outlined in dashes, is a fleeing family modeled after the California Interstate 5 immigrant crossing sign, which showed a family of three running with the word “CAUTION” above the figures. 14 However, in Everything All at Once it is the woman who leads her family to safety, a tribute to Xicanx matriarchs, whose role has often been diminished due the patriarchal societal order.15

The mother leads her family away from a shooting arrow that is implied to be a weapon deployed by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). The gleaming orange and red hilos superimposed over a painted city grid of Oakland stand in for the treasures of gold and silver stolen from the Americas. The red and orange streets denote the Indigenous bloodshed that was created in the name of the Gold Rush. By placing the family above the destructive city grid, Jimenez Underwood emphasizes Indigenous survival across the Americas. The family symbolizes that despite the settler hunt for gold and silver, the true treasures were never stolen from the Americas, because the true treasures are with its people.

Toward the bottom of the installation is a fragmented barbed-wired fence wrapped with glitterthread and colorful flowers. Jimenez Underwood refers to the wire as “power-wands” that are “shiny treasures,” and a metaphor for the beauty that migrant families create in the U.S. despite having to flee their homelands. 16 Rather than reproducing the trauma caused by the border barbed wire, the disjointed power-wand fence serves as a decorative offering of beauty for those who have been discarded and dehumanized by the U.S. Cutting through the power-wand fence are nopales made from chicken wire. The choice of material for the nopales is rooted in Jimenez Underwood’s childhood memory as a farmworker. Chicken wire—dangerous, strong, and tough—was used as a border to keep things in and out of farm spaces. She explains that American farmers tried to restrict nopales from growing on their property, but to Jimenez Underwood nopales were eaten as a source of life, nourishment, and medicine, and a symbol of her roots and her resilience.

The U.S.-Mexico border cuts through the entire installation. Three-inch nails run along the painted black border to create a weaving structure where Jimenez Underwood weaves a weft of leather barbed wire, used to indicate the fragility of the man-made line. Along this division are ten white “X” marks, representing the 1990s militarization of border-city crossings. 17 Using this broad painted strip in place of the border, Jimenez Underwood evokes queer feminist scholar Gloria Anzaldúa’s metaphor of the US-Mexico border as an open wound that never heals.18 In this instance, the black line can be symbolic of a scab torn open by the military checkpoints. 19 And although this installation carries a lot of destruction, it also sustains a message of pride, strength, and beauty. This positive message is represented by the eagle that flies over the escaping family, which the artist made from a plain weave of brown and gold wire, which makes the eagle appear visible only from certain angles, capturing “the essence of the eagle.” 20 She has conceived the eagle after the United Farm Workers’ logo as an homage to César Chávez, who explained that they used the Aztec eagle because “when people see it, they know it means dignity.” 21 Through the eagle, Jimenez Underwood represents a people who are often invisible in society but whose persistence, self-worth, and bravery are always present.

The final symbol that Jimenez Underwood placed below the center of her installation is a metal and barbed-wire hoop, that stands in for a “you are here” icon on a map. The hoop is made from harsh materials because the artist is implicating the viewer in the dangers of man-made borders and the cycles of violence that comes with them. The hoop is meant to bring the viewer into the present day and offer insight as to what might happen in the future because of the ongoing violence created by borders. However, the hoop also symbolizes a non-hierarchical Indigenous perspective, which sees everything as being interconnected. 22 Thus, while surrounding the viewer with systemic borders and metaphorical borders of their own making, Jimenez Underwood invites the viewer to reconsider their ancestral history, the history of the land, and other living beings in it. With her hilo in hand, Jimenez Underwood offers abolitionist border practices and messages of affirmation, hope, pride, and dignity for many who have long been denied their humanity due to borders.

Endnotes

- Jack D. Forbes, Aztecas del Norte: The Chicanos of Aztlán (Greenwich, Conn: Fawcett Publication Fawcett, 1973), 75. ↩︎

- Consuelo Jimenez Underwood, interviewed by the author, Gualala, California, February 22, 2024. ↩︎

- “Barack Obama elected president in 2008,” CBS News, November 4, 2008, YouTube, 13:18, https://youtu.be/teet9pcl0VM?si=y9UsPNVy5–kQXH1K ↩︎

- Consuelo Jimenez Underwood, interviewed by the author, September 2, 2024. ↩︎

- Laura E. Pérez, “Prayers for the Planet: Reweaving the Natural and Social—Consuelo Jimenez Underwood’s Welcome to Flower-Landia, in Consuelo Jimenez Underwood: Art, Weaving, Vision, ed. Laura Perez and Ann Marie Leimer (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 86. ↩︎

- Serna, Cristina, “Decolonizing Aesthetics in Mexican and Xicana Fiber Art: The Art of Conseulo Jimenez Underwood and Georgina Santos,” in Perez and Leimer, Consuelo Jimenez Underwood, 164. ↩︎

- In the in the Northern Hemisphere, the North Star, Polaris, was used by enslaved peoples to guide them toward free states in the north. See more about Polaris at https://science.nasa.gov/solar-system/skywatching/what-is-the-north-star-and-how-do-you-find-it/ ↩︎

- “Our State Flowers” in The Book of Wildflowers: An Introduction to the Ways of Plant Life, Together with Biographies of 250 Representative Species and Chapters on Our State Flowers and Familiar Grasses, 21–28. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 1924. ↩︎

- Anand Pandian, “Butterfly Crossings Traversing Boundaries of Space and Species in North America,” Environmental Humanities 14, no. 2 (July 2022): 447. ↩︎

- Renée de la Torre, “Red Path (Camino Rojo)” in Encyclopedia of Latin American Religions, ed Gooren, Henri. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019), 270. ↩︎

- In weaving, a twill is one of the strongest weaving structures since the threads get packed in tighter and it offers a range of flexibility and elasticity. This makes it so the weaving will not easily sag or warp when stretched. ↩︎

- Karen Mary Davalos, “Space, Place, and Belonging in Borderlines: Countermapping in the Art of Consuelo Jimenez Underwood,” in Consuelo Jimenez Underwood: Art, Weaving, Vision, ed. Laura Perez and Ann Marie Leimer (Duke University Press, 2022), 151. ↩︎

- The Borderline installations are part of an artistic abolitionist praxis that challenges colonial structures and institutions that enslave and dehumanize individuals based on labor and exploitative work practices. In 2013 María Esther Fernández curated Welcome to Flower-Landia, an exhibition that highlighted the Borderline series; see María Esther Fernández, “Consuelo Jimenez Underwood: Welcome to Flower-Landina Triton Museum of Art, Fall 2013” in Consuelo Jimenez Underwood: Art, Weaving, Vision ed. Laura Perez and Ann Marie Leimer (Duke University Press, 2022), 91–110. ↩︎

- Cindy Carcamo, “With Only One Left, Iconic Yellow Road Sign Showing Running Immigrants Now Borders on the Extinct.” Los Angeles Times, November 20, 2017, https://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-immigrants-running-road-sign–20170614–htmlstory.html ↩︎

- Irene Lara, “Goddess of the Américas in the Decolonial Imaginary: Beyond the Virtuous Virgen/Pagan Puta Dichotomy,” in Feminist Studies 34, nos. 1–2 (2008): 102. ↩︎

- Consuelo Jimenez Underwood, interview with the author, September 2, 2024. ↩︎

- Andrew Becker, “Frontline/World Mexico: Border Timeline,” PBS, https://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/mexico704/history/timeline.html. ↩︎

- Gloria E. Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 4th ed. (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 2007) 25. ↩︎

- Fernández, María Esther. “Consuelo Jimenez Underwood: Welcome to Flower-Landina Triton Museum of Art, Fall 2013,” in Consuelo Jimenez Underwood: Art, Weaving, Vision eds. Laura Perez and Ann Marie Leimer (Duke University Press, 2022), 97. ↩︎

- Oakland Museum of California. “Everything All at Once by Consuelo Jimenez Underwood at OMCA” Posted June 20, 2024, by Oakland Museum of California (OMCA), YouTube, 2:02 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c6cl_oYoFes. ↩︎

- “César Chávez (1927–1993).” National Portrait Gallery, March 2, 2017, https://npg.si.edu/learn/classroom-resource/cesar-chavez#:~:text=César%20Chávez%20Suggested%20Activities&text=That%20is%20why%20we%20chose,to%20demand%20their%20civil%20rights ↩︎

- Serna, Cristina, “Decolonizing Aesthetics in Mexican and Xicana Fiber Art: The Art of Consuelo Jimenez Underwood and Georgina Santos” in in Consuelo Jimenez Underwood: Art, Weaving, Vision eds. Laura Perez and Ann Marie Leimer (Duke University Press, 2022), 170. ↩︎

Gilda Posada is a Xicana artist, independent curator, and art historian from Southeast Los Angeles. She is a PhD candidate in the History of Art at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where she is completing her dissertation “Reigniting the Sacred Fire: An Analysis of Xicana-Indigenous and Queer Chicanx Art.”

Cite this essay: Gilda Posada, “Hilos and the Unraveling of Borders in the Work of Consuelo Jimenez Underwood” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, April 28 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/hilos-and-the-unraveling-of-borders-in-the-work-of-consuelo-jimenez-underwood/