Carmelita Tropicana: Recordar es Vivir

Memories of Cuba do not come back on command. They erupt in waves, like a storm surge lashing against the Malecon’s weathered concrete. The process of releasing painful memories is essential for personal healing and reconciliation, and this challenge is particularly evident within the Cuban-American diaspora. Memory is a powerful, often fragile force that shapes our identity, holding both pain and the potential for transformation. This process of release and reconciliation, as explored in Alina Troyano’s 1994 camp performance Milk of Amnesia, facilitates a return to the present reality.

Troyano’s work speaks to the healing and therapeutic impact that performance can have on both its actor and audience. If recordar es vivir (to remember is to live), a commonly heard Spanish phrase derived from a Daniel Santos bolero, then what happens when you recreate or reperform a memory? Perhaps the act of performance can connect across generations and, in turn, heal.

In Milk of Amnesia, Troyano’s “cubana dyke camp” persona,1 Carmelita Tropicana, suffers a bout of amnesia and attempts to jolt her memory about her identity by performing ordinary tasks throughout her life. Troyano’s disaffected narration in Milk of Amnesia, reminiscent of narrator Sergio in the 1968 Cuban film Memories of Underdevelopment, offers a sobering contrast to her camp caricatures of Cuban stereotypes—the overly self serious machismo of Pingalito, and the unserious hyperfemininity of Tropicana.2

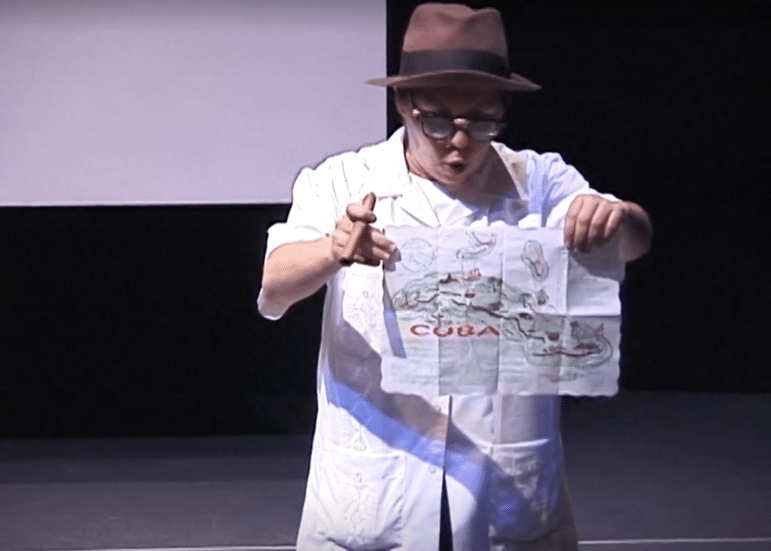

In Milk of Amnesia, Troyano opens the show in female-to-male drag as Pingalito Betancourt, a macho elder Cuban man, dando muela, a typical macho posturing, to the audience as he talks about how he wants to cure Carmelita’s amnesia. Pingalito, first introduced in Troyano’s 1987 Memories of the Revolution, is a diminutive of the Cuban word for penis, and represents a form of Cuban macho jingoism. 3 But Troyano undermines the patriarchal character of Cuban and Cuban-American identity through choteo, contesting the bourgeois conventions within the Cuban exile community.

Troyano’s hybridity relies on camp, choteo (a type of joke and humor), and Cuban burla, as disidentifying practices to disarm the viewer through humor. 4 As Muñoz described, Troyano is able to offer cultural critique of the machista Cuban identity by subverting it through humor and drag performances, weaving between the Lucy and Desi–influenced character of Carmelita, the female to male drag performance of Pingalito, and finally, embodying a pig. It is through this queer hybridity and the ping-ponging of characters that Troyano addresses cultural multiplicity and personal history, and ultimately reconciles Carmelita’s memory.

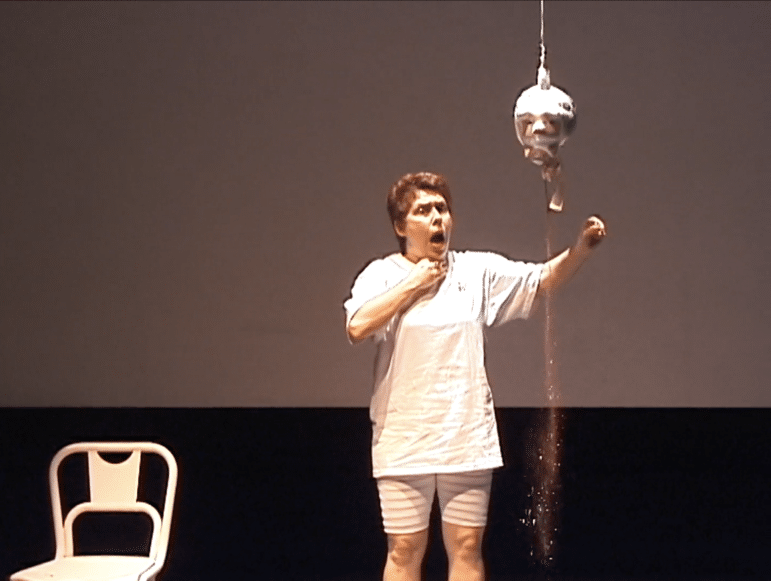

At the performance’s conclusion, the character orders a pan con lechon at Hemingway’s favorite restaurant. But when the pork falls to the ground, a papier-mâché pig descends from the theater’s ceiling. The pig’s spirit seemingly possesses Carmelita and relives its own immigrant narrative from an idyllic farm to the tight corners of a Havana apartment. The pig, exiled and commodified through its intended consumption—in ways no different than the objectification of female and queer bodies in Cuban cultures—behaves as a conduit for Carmelita’s own desire for remembering. In an instant, Carmelita and the pig are united when the pig sees blue tiles through the holes of its cardboard container as it is about to have his vocal cords cut. Carmelita’s memory is suddenly restored upon seeing the blue tiles, “My vocal cords, my tonsils. The pig and I had our operations in the same clinic. The clinic with blue tiles. I remember.”

The pig in this narrative serves not only as a cultural reference to traditional Cuban practices, such as roasting a pig for annual New Year traditions, but also as a conduit for exploring historical memory. The subjectivity of the pig’s perspective references the impact of Cuba’s Special Period, when government officials approved the raising of pigs in previously unthinkable places. 5 Many families would have relationships with their pigs, and try to give them a good life with the goal of sacrificing them at a holiday or special meal. The pig, stabbed and killed, coincides with the moment Carmelita regains her memory. It is through the wounding and penetration of flesh that Carmelita becomes once again embodied.

Upon reconciling her memory, Carmelita shouts, “We are all connected. But not through email, internet—through memory, history, horse-tory!” Here, materiality and embodiment becomes a vessel to purge and expel memory, enabling the audience to engage with complex themes of identity and history.

Milk of Amnesia’s title immediately evokes a sense of dislocation and disruption—similar to the blood released in the form of red glitter from the pig’s papier-mâché body on stage when it is sacrificed. Milk of Magnesia is the brand of mild laxative, which helps to “cleanse” the digestive system, suggesting that the body needs a mechanism of relief or a release from internal turmoil. Tropicana’s “milk of amnesia,” however, suggests an emotional or psychological cleansing—an erasure of memory and identity, one that is often triggered by trauma or the denial of cultural roots. This relationship between amnesia and memory formation is crucial to understanding the performative gesture as a means of both accessing and suppressing the past.

As Troyano noted, “Carmelita goes into different people’s bodies.” 6 This hybridized self reflects the survivalist approach of what Muñoz refers to as “dyke self-fabrication.” 7 Troyano rose as an artist while frequenting the queer feminist performance spaces of the 1980s and ’90s, particularly the WOW Café, where many queer and feminist artists were rethinking the boundaries of performance art. Carmelita Tropicana’s use of humor and gesture is deeply embedded in this cultural moment, where language and the body were reclaimed as sites of personal and political resistance. By performing various characters—male, female, and animal—Troyano is reconstructing her own identity as a Cuban lesbian North American immigrant. To become embodied, Troyano suggests, we must first be disembodied.

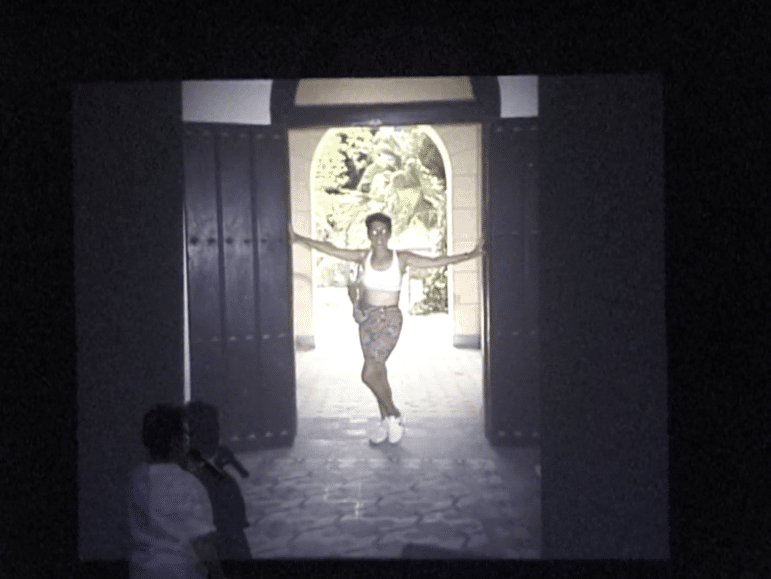

“All my work in the ’80s is pre-Castro, until I went to Cuba [in 1993],” said Troyano, who traveled to Cuba the year before writing Milk of Amnesia. “Until I went to Cuba, I didn’t feel like I could speak about the Cuban Revolution or who Castro was.” 8 Troyano reflects this experience within Milk of Amnesia when the artist breaks from her persona and presents a slideshow of photos from Troyano’s own visit to Cuba the prior year. The photos interject Carmelita’s attempts to spark her memory after she awakens from a coma and cannot recall her identity. But the photos are from Troyano’s family’s home in Havana, where she lived before emigrating to the United States in the 1960s. In a Spanish-language voiceover narration, Carmelita returns to her creator’s identity–and for a moment, remembers how she felt like a tourist in what was once her own home. As the phrase recordar es vivir promises, in order to remember, Troyano relived her physical space. But, Troyano’s narration, which is filled with omniscient grief, hints that sometimes, fully reconnecting with the past is not possible.

In this sense, Troyano’s work reminds its viewers that you cannot understand something until you’ve experienced it. If direct experience is inaccessible, as it is for most Cubans in exile, then performance becomes the conduit for remembering and, therefore, understanding.

The role of memory in Tropicana’s work cannot be separated from its embodiment in the physical space of performance. In Milk of Amnesia, memory is not just a mental process, but is located in the body’s gestures, facial expressions, and the way it occupies space. Tropicana’s work, despite its monologic format, is still deeply concerned with embodiment—specifically, the materiality of queer memory. The idea that memory extends and is taken in the body is crucial here, as it implies that memories are not static but are continually formed and reformed through the physicality of the performance. Tropicana’s work invites the audience to witness the transformation of memory as it moves from one body to another: it is experienced, embodied, and consumed by the viewers.

Tropicana’s performances often address the inability to fully reconnect with or recover the past, especially when that past is marked by exile, displacement, and the erasure of cultural histories. Her struggle to recover the lost memories of her Cuban heritage, the trauma of immigration, and the fractured nature of diasporic identity are deeply entwined with the theme of Jack Halberstam’s queer failure: a failure to reconcile disparate parts of her identity—the societally acceptable and what is deemed different, to forge a coherent narrative in the face of cultural and historical erasure.

However, this failure is not presented as a deficit. On the contrary, it becomes a radical space of resistance, where the absence or incompleteness of memory is itself a form of agency—Troyano’s queerness, her existence outside of the traditional Cuban gender norms has birthed its own identity. Tropicana’s use of humor in this context—through language, gesture, and the absurdity of her performances—becomes a mode of survival and a critique of normative identity formations. Troyano’s insights underscore that memories are not static: they are dynamic forces that evolve through the materials we choose, the performances we create, and the narratives we tell.

For the Cuban diaspora, the inability to visit the island and confront grief directly has led to unresolved trauma. This unprocessed pain, coupled with a resistance to recontextualizing the past, has fractured the Cuban American identity, appeasing American conservative ideals over their origins of national identity. What is needed, perhaps, is a reckoning, similar to Troyano’s performance of transformative realization—where coming to terms with one’s identity, independent of political or societal implications, offers a path to liberation.

Endnotes

- José Esteban Muñoz writes that Carmelita Tropicana’s performance connotes the importance of cultural enactment he refers to as cubana dyke camp. Camp refers to a style of performance and reception that relies on humor to examine social and cultural forms. José E. Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 119-141. ↩︎

- The documentary-style fiction film follows Sergio, a disengaged and affluent writer who decides to stay in Havana following the revolution. Over time, he witnesses the impacts of the promised revolution. ↩︎

- A nod to Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment, Pingalito performs an exaggerated Sergio character, where Sergio is an intellectual, disaffected Cuban male, Pingalito is bombastic, hyper masculine, and pines for a mythical lost Cuba. ↩︎

- Muñoz writes that hybridity is one way to discuss the crossfire of influences, affiliations or politics that happen between a lesbian identity and in the intersection of Cuban and North American traditions of performance. Muñoz, Disidentifications, 119-141. ↩︎

- During the Special Period, Cuba experienced a period of widespread food insecurity due to the collapse of the Soviet Union. ↩︎

- Alina Troyano, personal communication with the author, September 4, 2024. ↩︎

- Muñoz, Disidentifications, 138. ↩︎

- Troyano, personal communication with the author. ↩︎

Alexandra Martinez is a Cuban-American writer and filmmaker. Her writing spans such topics as immigration, the affordable housing crisis, and art-washing, and appears in publications including Hyperallergic and The Art Newspaper. She is based in Miami where she lives with her young daughter and enjoys tending to her native pine rockland garden. She is a 2024 recipient of the Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant in the short-form writing category.

Cite this essay: Alexandra Martinez, “Carmelita Tropicana: Recordar es Vivir,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, April 28, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/carmelita-tropicana-recordar-es-vivir/