Freedom Denied

You have set foot inside a family-owned food joint, one of many in your city. This one appears to sell pizza, their sizes displayed in round dishes and called personal, small, medium, large, and family. But pizza is not on the menu. As you inch closer to the walls, you find they are half real. The wood paneling, dimly lit, is nothing more than a photograph, stretching to the edges of this wooden canvas. This is an art installation made of four walls angled against each other. To the right, you can peer into the kitchen. The workers prepping your pizza are frozen in time. The series of menus on the long wall present real menus with items and prices hand lettered in classic sign-painter’s red and black block lettering; these are each mostly covered by photographs of a text disguised in that same menu format and layout that instead tell a story in a human tone. That text begins: “The visiting period was my family coming to visit me, taking me away from everything.” 1

This scene is in Personal, Small, Medium, Large, Family (2021), a piece by artist Mario Ybarra Jr., and tells the story of a life spent incarcerated: the life of Richard Cerna. He is the artist’s childhood friend, who was sentenced to life imprisonment when the two were teenagers. In the end, Cerna spent thirty-two years incarcerated before he was released. His words now line the walls of this life-size replica of Red West Pizzeria, the local pizza joint Cerna and Ybarra spent time in during the 1970s and ’80s, while growing up in the Wilmington neighborhood of Los Angeles. Ybarra, proudly identifying as a Mexican American artist, carries this upbringing in his identity. His storytelling is steeped in cultural histories, seeking to amplify stories often forgotten, hidden within the margins. Ybarra often asks his audience to contemplate different realities, to make connections between the inside and outside. This time, the pizza joint asks you to consider: How does someone survive the carceral system? What is left of them on the outside?

It took my freedom to be taken from me

to realize all the stuff I had taken for granted.—Richard Cerna

In literature by the National Institute of Corrections, nestled among descriptions of the many types of facilities that hold young people and the many facets of this part of the carceral system, you can find the following line: “Confining youth—in most circumstances—is not in the best interest of either youth or public safety.” 2 Richard Cerna’s story lives somewhere in that sentence.

For years, Ybarra’s practice has engaged with similar questions and modes of storytelling as the ones seen in the pizza shop. In a piece from almost a decade before, like a cow visiting a butchershop (2013), Ybarra built a butcher shop full of irony. At the center is a musical stage with various instruments, including djembe drums, maracas, and flutes, all arranged around a butcher table, which reads “BUSTIN’ MY CHOPS” on the side. The installation walls are lined with newsprint, with detailed cuts of meat made of painted plywood strewn about. You can draw parallels from the first piece onto the second, the witty, ironic title, or the scene-scaping. In butchershop, Ybarra criticizes the art fair establishment, placing the artist as commodified and ready for consumption—a cut of meat at the butcher’s. At the pizza shop, he explores the carceral system in a similar manner, by using a metaphor. In the time elapsed between the two pieces, his technique and scale has expanded, yet his critical eye persists.

Back at the pizzeria, everything is standing still, waiting for you. Perhaps it’s a metaphor for a life spent in isolation, suspended from reality. It’s all in the details: the printed life-size image of a real pizza shop, with images of real workers to one side and all the components of the pizza shop re-created and hung on top of the massive photographic mural. By making all these objects tangible and to full scale, Ybarra invites us into a memory of growing up, of what went missing. By his own hands, the artist has found a way to revisit a memory, to change it, to expand upon it. It’s a way to pay tribute via a form of doubling, a way to use our bodies to retrace Ybarra’s and Cerna’s steps, and then bear witness.

And this is my family time. Now with you guys

I feel like I’m with you guys outside.—Richard Cerna

In traditional gallery spaces, visitors must abstain from touching the art and are required to stand a few feet from the walls and observe. In the carceral system, touch with outsiders is regulated, monitored, and sometimes punishable. Here, at the pizza shop, you are on the outside, with Cerna.

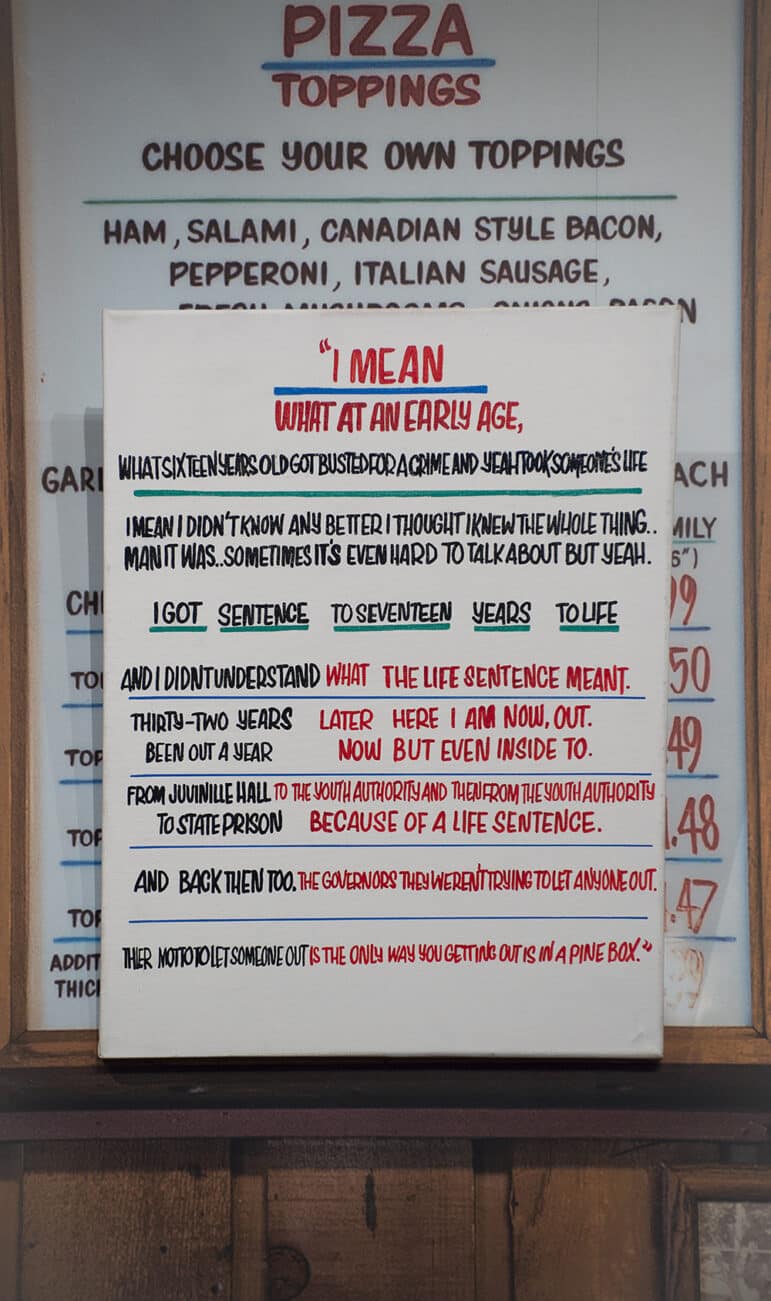

The food joint is built with interaction in mind. You are free to walk through the space or to sit on the bar stools, the way you would in a real pizza shop after placing an order. Near these stools are a pair of headphones and three screens to hold your attention. The middle screen plays an interview with Cerna himself, conducted by the artist. The text on the menus are poignant excerpts from this conversation. In small letters, all squished together, at the very bottom of one of the menus, you can find one of the most poignant quotes from Cerna, about the finality of most prison sentences: “Their motto to let someone out is: ‘The only way you getting out is in a pine box.’”

When you walk around to the back of the work, you find elements purposefully unfinished, the raw wood of the supports keeping the walls upright, a cord powering the screens plugged into the floor. Here Ybarra has completed this ode to Cerna with intimate photographs of their lives. One set of family photos features the same people decades apart, before and after incarceration. Another photo, from inside the real pizza joint, features the Wilmington Willhall Baseball Association’s class of 1984, with Richard Cerna’s childhood body outlined in red.

The photographs remind us that the story starts and ends with Cerna. In between, the effects of his imprisonment bleed beyond him, into his family and community. Ybarra finds a way to materially speak about the impact of incarceration. He does so through concentric circles: the sizes of pizza pans. It’s right in the title: Personal, Small, Medium, Large, Family. It’s a metaphor made material, tangible, familiar.

Life spent incarcerated is a form of violence, a life of being subjected to a taxing and dehumanizing system that doesn’t seek to reintegrate individuals or better their lives but instead seeks profit, punishment, and labor. Research published by The Sentencing Project 3 finds that young people of color are more likely than their white counterparts to be held in correctional facilities. Among people under the age of twenty-five at the time of their arrest, individuals who are Black and Latino are more likely to receive life sentences. 4

Cerna speaks about how he tried to stay focused, find joy, and pursue an education during his incarceration. It is these ideas that Ybarra expands upon in other elements of the piece. He returns to the doubling, to using the body to pay tribute by retracing steps. The right and left monitors rotate from a video of the Red West Pizza workers to a video Ybarra recorded of himself, submerging his feet in the Pacific Ocean—one of the first acts of freedom Cerna took upon his release. “That’s one thing I have always wanted to do, just always keep my mind going on something because if I didn’t man it just feels like everything is crashing down on you,” the menu tells us.

The pizza shop piece is an intimate rumination, an extraction on life. It is a rich ode to a life perhaps once thought of as closed off, hidden. The last panel, the last menu, contains a long quote from Cerna. All the words struggle to fit together. They are crammed in with urgency, the urgency you can imagine Cerna carried when speaking. The breaks and outlines push and pull like Cerna’s extemporaneous speech. “I didn’t know any better. I thought I knew the whole thing . . . And I didn’t understand what the life sentence meant.” Somewhere else in the installation, Cerna says: “I just make the best of things. That’s the way I look at it, just make the best of things.” 5

Endnotes

- The menu text is transcribed from a video interview between Ybarra Jr, and Cerna, which was played on monitors within the installation. ↩︎

- https://info.nicic.gov/desktop-guide/principles-and-concepts/ch2–types-facilities (page no longer active). An archived link is available: https://web.archive.org/web/20240815154450/https://info.nicic.gov/desktop-guide/principles-and-concepts/ch2-types-facilities ↩︎

- Joshua Rovner, “Youth Justice by the Numbers,” August 14, 2024, The Sentencing Project, https://www.sentencingproject.org/policy-brief/youth-justice-by-the-numbers/ ↩︎

- Ashley Nellis and Celeste Barry, “A Matter of Life: The Scope and Impact of Life and Long-Term Imprisonment in the United States,” January 8, 2025, The Sentencing Project, https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/a-matter-of-life-the-scope-and-impact-of-life-and-long-term-imprisonment-in-the-united-states. ↩︎

- Richard Cerna, transcription from interview with Mario Ybarra Jr from menu cards in Personal, Small, Medium, Large, Family. ↩︎

Lille Allen is a Latinx designer and writer based in Las Vegas, NV. She is currently a designer at Eater. Previously, Lille was the Associate Art Director at The Believer. Her writing can be found in Hyperallergic and McSweeney’s.

Cite this essay: Lille Allen, “Freedom Denied,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, April 28, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/freedom-denied/