Bend’s Bends: Christina Fernandez’s De- and Re-Materialization of Memory

In a video interview Los Angeles–based artist Christina Fernandez describes Bend, which the artist has now substantively re-created several times (1998, 2014, 2020), as one of three works she produced after her 1990s travel to Oaxaca, Mexico.1 In this essay, I focus on Bend’s post-2020 version, which consists of a photographic and text wall mural (variable dimensions up to 11 ft. 6 in. × 19 ft.) and five pigment prints (each 20 × 30 in.), four of which also comprise the series Ruin.2 The mural features a panoramic photograph of archaeological-becoming-allegorical ruins, hilly terrain, and clouds. Two columns of text in white font, as if color-reversed to condense the ephemerality of language, flank its accompanying pigment prints, superimposed on the mural. Starting with a close reading of this version of the work, I follow Bend’s bends—internalized and scattered across its iterations—approaching the project as offering both a theory of clouds and windows onto the artist’s decades-long practice, self-described as an “oscillation between landscape and portrait photography.” 3 In conclusion, I also briefly breathe in and with Bend’s de- and re-materialization of memory, Fernandez’s and my own.

Bend’s post-2020 columns of text, oriented vertically, shimmer to coalesce as a travel narrative, seemingly in inverse proportion to one of the artist’s earlier image-text installations Maria’s Great Expedition, which tracks Fernandez’s great-grandmother from Morelia, Michoacán; to Portland, Colorado; back to Morelia; on to Phoenix, Arizona; Boyle Heights in Los Angeles; and San Diego, California. With a map, a text exceeding the length of conventional captions, and six photographs in the project, Fernandez performs each relocation, sometimes emulating the photographic conventions of the time period referenced (e.g., Dorothea Lange’s 1930s photos), 4 overall demonstrating the affinities of the series with the work of past and contemporary woman-identified artists who blur the boundaries of performance and photography (e.g., Cindy Sherman, Eleanor Antin, and Carrie Mae Weems). Visual studies scholar Chon A. Noriega, who commissioned the project for the exhibition From the West: Chicano Narrative Photography (1995, The Mexican Museum, San Francisco), observes that some curators have since asked to separate the map and text from the photographs. He roundly critiques the request’s a priori fallacy: “The text and map situate the photographs within a larger visual culture, exhibition pedagogy, and social history. Removing these elements does not eliminate the contexts, but it fractures the image-text artwork.” 5 The effect, he explains, obscures the significance of Maria’s Great Expedition as a social allegory of the historical circumstances exceeding one woman’s life experience. 6

Just as Noriega reads the components of Maria’s Great Expedition in concert, I approach the post-2020 version of Bend’s myriad formal elements—its textual columns, image sequence, and layering—as interconnected. Simultaneously, I recognize that Bend, unlike Maria’s Great Expedition, increasingly has wielded the allegorical in opposition to—versus in the service of—social allegories. I begin with a close reading of the project’s columns because, despite their appearance of fading into the mural’s panoramic photograph, the duo, like the text of Maria’s Great Expedition, time-cue this version of Bend’s bends. Segmented into six paragraphs by single lines in bold italics, Bend’s columns more specifically visualize language’s materiality as one marker of the atmospheric conditions of any interior monologue’s nonlinear progression. With the artist we arrive at Monte Albán. 7 Fernandez’s back is weary, weighed down by camera equipment and expectation. She recalls leaving LA “to find a part of myself in the city and ruins of Oaxaca” after hearing from friends of the state’s idyllic architecture, archaeological zones, and inhabitants. 8 The narrative folds as the artist checks her internalization of an “image of Oaxaca as a sort of pastoral, silent and archaic . . . in which I could rest and not be bothered by the traffic and hustle of Los Angeles” against the recollection of her recent public transport ride from the Oaxaca City airport, another iteration of “traffic and hustle.” Her account bends forward to Monte Albán’s tomb 104, or more precisely to an interaction between herself and a guide who volunteers to hold up a piece of sheet metal to bend sunlight onto what the artist first perceives to be a funerary urn of Cocijo, the Zapotec god of lightning. Fernandez autocorrects, “What I thought was a representation of Cocijo is instead a representation of the dead interned in tomb 104 as Cocijo; transformed, taking on Cocijo’s attributes, into the people of the clouds.” Fernandez references Zapotec cosmology’s understanding of the afterlife as wind, breath, or spirit—pée—a durational force of creation and disturbance. She elaborates that the vessel, maintained for the dead’s visitations to the living, acts as a waystation for pée. The narrative peripeteia facilitates Fernandez’s subsequent projection of a life story onto a woman’s skeletal remains displayed in a floor cubicle of Monte Albán’s museum. The artist’s conjecture, a “critical fabulation,” triggers the text’s final bend, a flashback as striking as a deus ex machina bolt of lightning (perhaps Cocijo’s reappearance as vanishing mediator). 9 Fernandez’s maternal grandmother Dolores, laboring to breathe in an Orange County hospital on a respirator, rounds another bend, is re-conjugated in the past tense of “passed”—the narrative’s last word, fashioned to eschew social allegory in favor of sculpting Bend into a repository for pée—the ancestor’s, quick-cycling between the de- and re-materialization of memory. 10

Bend’s dialectical synthesis of textual images—to call the movement by another name—neither begins nor ends with the columns’ nimble calisthenics, however. Rather, the textual columns are braced by a crossbeam of pigment prints that guarantees the project its overarching reparative allegorical bent against social allegory. Side by side, scored like a contact sheet, mosaic frieze, or predella, the five prints interstitially raise Bend’s respective photographic image count and its locative waypoints to six. Although the double columns of the mural’s text allude to LA, Oaxaca City, Monte Albán, and Orange County, paired photographs, either side of the series’ center “fold,” supply the viewer with a parallel itinerary. Left to right, image one depicts a curved intersection of two of Monte Albán’s walls. Where the walls meet, the viewer’s gaze floats upward to cloud banks. Images two and four correspond to the archaeological remains of dwellings, possibly tombs, and stone steps at Dainzú, as if following the well-tread paths between earth and sky of the site’s former inhabitants, the viewer might scale a stairway to heaven. 11 The fifth and final print foregrounds the iconic mosaic fretwork of Mitla either side of an open window presciently suggestive of Fernandez’s photographic series View from Here (2016–ongoing) that also features windows’ framing land- and cloudscapes. 12

Courtesy of the artist.

In a 2007 interview with poet-art historian Roberto Tejada, Fernandez is forthcoming about her initial discomfort with Ruin, presenting viewers with a unique window onto her reuse of four of the series’ photos in Bend: “I didn’t like the photographs. I printed them and they’re beautiful, but . . . . It’s very difficult to do anything new with these ancient, incredible ruins.” 13 She elaborates, registering a disjuncture between her LA Chicanx community’s valorizations of Indigeneity, post-revolutionary Mexican cultural nationalisms’ strategic mobilization of the figure of the Indigenous, and the quotidian discrimination she witnessed against Oaxaca’s Indigenous communities in the 1990s. Does Fernandez’s reckoning with the cognitive dissonance she details sit, or more aptly put, stand, like a purloined letter at the center of the pigment prints? Extrapolating forward, does it inform the artist’s reconsideration of the project’s layout after its initial 1998, 2014, and 2019 presentations?

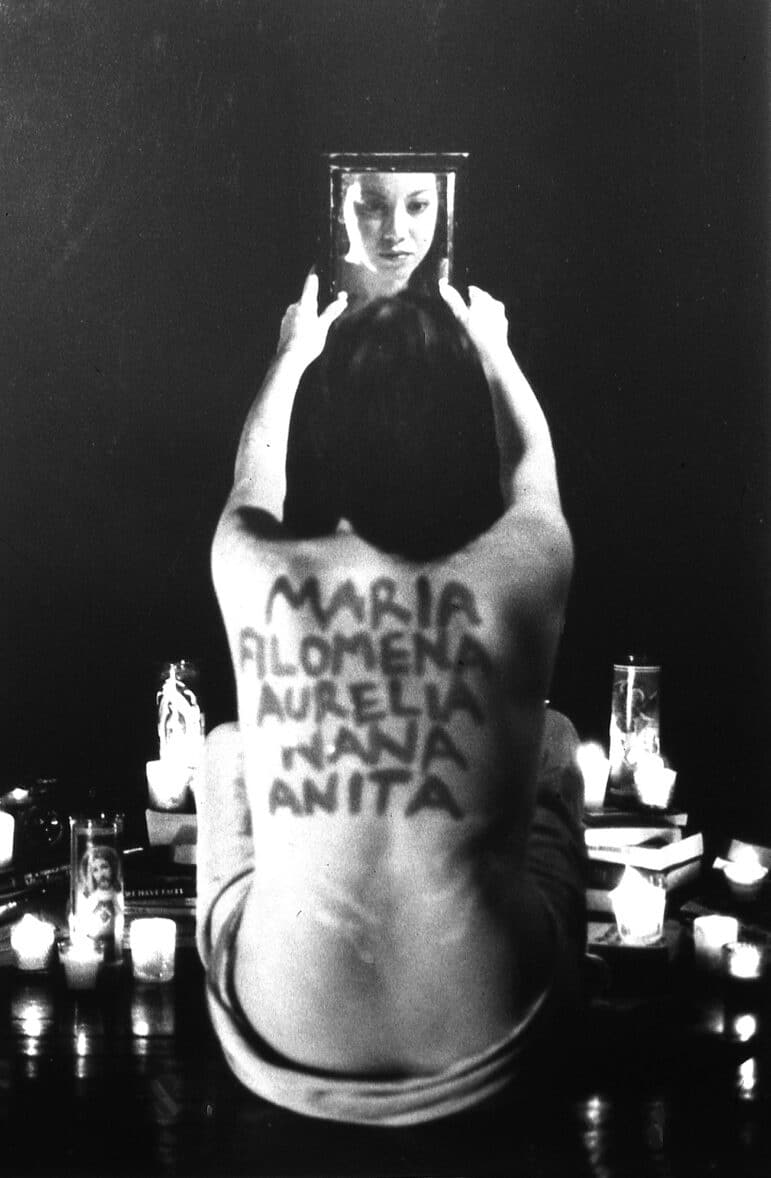

Between the paired Dainzú images, Bend’s only vertical print bears some resemblance to Fernandez’s ghosting of popular culture, roughly contemporaneous with the project’s earliest articulation. 14 In the series Untitled Multiple Exposures (1999), Fernandez zooms in on images and stills of Indigenous Mexicans by photographers and cinematographers (Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Luis Buñuel, Tina Modotti, Nacho López), work that informs what Tejada terms Mexico’s “image environment.” 15 The artist then overlays those close-ups with photographs of herself. The de facto self-portraits, like the central pigment print of Bend, feature Fernandez bending into other historically informed modes of channeling Woman, distinct from the artist’s embodied performance in Maria’s Great Expedition.16 Half-rhyming with photographic documentation of body art by Ana Mendieta, also produced in Oaxaca, while simultaneously offering a “phantom citing” of the classic anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), the central print in which Fernandez turns her back on the “national camera” mirrors the columns’ opening description of the artist’s weariness. 17 It conjures the artist’s prior self-portraiture, notably “My Family and Me” from the series Sin Cool (1992–93), wherein Fernandez’s bares her back to reveal the handwritten names of female-identified relatives. 18 Alternately, the allegorical figuration of Woman, visually inset as the vessel propped in Tomb 104’s niche in this iteration of Bend, acts indeed is more fully realized as the map and diagram’s overarching legend. It reinforces the project’s construction on a narrative grid, replete with x and y axes—the better to plot spatial coordinates and temporal kinships! The central pigment print, Bend’s punctum, like an interjection in crowded public transport, marshals the project’s elaboration of two sets of “allegorical ruins,” suspending both in luminous “Brownian motion.” 19 The lines that the artist-performing-Woman models, smudged horizontally and vertically, become the central spine or third column of Bend, sturdy enough to shoulder an implicit critique of the “bent,” ruinous trope of travel as mnemonic device, too.

Of Bend and Ruin, Pérez proposes, “the image-as-information (rather than representation) . . . figure[s] the ambiguity of presence . . . to produce the effect of haunting.” 20 But, what if the effect of haunting here, assuming the shape of the visible aggregation of animated droplets in air (if we sixth-sense Brownian motion once again), were to be read even more broadly as the aesthetic and political double-crossing of the image-as-information and the image-as-representation? Significantly, Pérez does not address the dynamic layout of Bend’s most recent articulation because, as Fernandez clarifies, “there was no wall mural” at the time that Pérez was writing about the project. 21 Building on Pérez’s generative interpretations of spirituality in Chicana art and recalling Noriega’s injunctive to read Maria’s Great Expedition holistically, however, we might recognize that the centered print of Bend’s post-2020 layout, like the curved corner of the walls’ intersection in “Monte Albán,” levitates the viewer’s gaze upward to the mural’s panoramic photograph “Cerro de la Campana”—so much backgrounded “ruin” and sky—as if the work in its entirety, up to and including its narrative momenta (across its many iterations), functioned as an altar in remembrance of the persistent presencing of Fernandez’s grandmother and the “people of the clouds.” 22 Parts to whole, Bend folds deeper into what Pérez terms “altarity,” a historical materialism, against or despite the alterity assigned to Indigeneity and femininity in epic Histories configured as cultural nationalisms’ social allegories.

Fernandez has presented Bend six times (1998, 2014, 2019, 2020, 2023, 2024). Returning to the project more than twenty-five years after its initial presentation, in the thick of the COVID pandemic (notwithstanding declarations of the latter’s end), Mexico’s “uncivil wars,” the militarization of policing and borders worldwide, after the 2024 Mexican and US Presidential elections and the 2025 Los Angeles fires, Bend acquires additional resonances for me—so much labored breathing, pée rising skyward but also revisiting the living. A composite and index of the interpellation of performance and photography across Fernandez’s decades-long practice, representative of the artist’s “oscillation between landscape and portrait photography,” Bend, like a piece of sheet metal held up to bend light—in physics already the confluence of spacetime—forwards a “theory of clouds” bound to the de- and re-materialization of memory, the artist’s and my own.

Endnotes

- See Christina Fernandez in “Christina Fernandez: Bend,” nd, accessed March 28, 2025, https://galleryluisotti.com/media_items/christina-fernandez-bend/?artist=christina-fernandez.

Fernandez, who received a BA from the University of California, Los Angeles (1989) and an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts (1996), has taught since 2001 at Cerritos College in Norwalk, California. When I write that Fernandez has “re/created” Bend, I mean that the project has enjoyed more than one layout “across time and from one site to the next,” to invoke the language of the editor of this volume, Mary Thomas (personal communication with the author, February 28, 2025). Many thanks to Thomas for thinking with me about the implications of Bend’s versioning throughout the process of my writing various versions of this essay. Many thanks to Fernandez for sharing documentation of Bend’s 2019 presentation, for recounting the work’s 1998 articulation, and for clarifying that earlier versions of Bend should be understood as distinct from the work’s post-2020 version. Christina Fernandez, personal communications with the author, (February 23, March 6, March 10, March 11, and April 7, 2025). I will return to Bend’s variations as meta “bends” of the project at the close of this essay. ↩︎ - I concentrate on this version of Bend because, as Fernandez shared, it is the one included in the permanent collections of the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Christina Fernandez, personal communications with the author, March 10, 2025. Fernandez first restaged this version in Gallery Luisotti (Los Angeles, CA), which also represents the artist, in 2020. Fernandez elsewhere clarifies that this version feels most “complete” (Christina Fernandez in “Christina Fernandez: Bend”). ↩︎

- When I write a “theory of clouds,” I tangentially brush, light as cumulonimbus, up against art historian Hubert Damisch’s A Theory of /Cloud/, which postulates that the development of linear perspective in painting cannot be understood without thinking conterminously the amorphous presencing of the cloud. Hubert Damisch, A Theory of /Cloud/ Toward a History of Painting, trans. Janet Lloyd (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002). I pluralize “clouds” because Fernandez multiplies cloud banks in both Ruin and Bend. Christina Fernandez in conversation with Joanna Szupinska, “Multiple Exposures,” 2022, accessed August 17, 2024, https://galleryluisotti.com/media_items/christina-fernandez-multiple-exposures/?artist=christina-fernandez and Christina Fernandez, “LACMA: Christina Fernandez | Golden Hour Exhibition,” accessed August 25, 2024, https://galleryluisotti.com/media_items/christina-fernandez-l-golden-hour-exhibition/?artist=christina-fernandez. ↩︎

- Christina Fernandez, personal communication with the author, March 11, 2025. ↩︎

- Chon A. Noreiga, “To Dwell on This Matrix of Places” in Chon A. Noreiga, Mari Carmen Ramírez, and Pilar Tompkins Rivas, eds., Home—So Different, So Appealing (Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Press, 2017), 30. ↩︎

- More precisely Noriega writes, “Fernandez resists or downplays personal biography in place of social allegory, identifying neither Maria as her great-grandmother nor herself as the model.” Chon A. Noriega, ed., From the West: Chicano Narrative Photography (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995), 13. ↩︎

- Monte Albán (500 BCE–800 CE), designated as a World Heritage Site in 1987 by UNESCO, located eight kilometers from what’s now Oaxaca City, is renowned for its stone tombs, intricate murals depicting funerary rituals, and ceramics, including the vessel in the likeness of Cocijo that Fernandez cites in Bend and to wit I shortly turn. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, “Monte Albán,” Gobierno de México, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.inah.gob.mx/zonas/94-zona-arqueologica-de-monte-alban. ↩︎

- All text cited here and in the description of the columns that immediately follows is from the artwork proper. ↩︎

- In Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2019), cultural studies scholar and theorist Saidiya Hartman develops the historiographic methodology of “critical fabulation,” writing, “I have pressed at the limits of the case file and the document, speculated about what might have been, . . . amplified moments of withholding, escape and possibility, moments when the vision and dreams of the wayward seemed possible” (xv). ↩︎

- Many thanks to the artist for clarifying that the reference here is to Dolores, Christina Fernandez, personal communication with the author, February 23, 2025. Notably, I’d add that the pastoral at the close of the text is doubled by the interred specter of theorist Michel Foucault’s writing on pastoral power. While a detailed examination of the latter clearly exceeds the scope of this essay, I refer to Foucault’s late work on the society of control’s mandates to “shepherd” the subject in Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978 (New York: Picador, 2009). ↩︎

- Dainzú (600 BCE–300 CE), 20 kilometers southeast of Oaxaca City, is celebrated for its stairs, bas-relief gallery of dignitaries and ball players, ballgame court, and tombs. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, “Dainzú,” Gobierno de México, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.inah.gob.mx/zonas/86-zona-arqueologica-dainzu. ↩︎

- While Monte Albán served as a political and economic hub for Zapotec civilization, Mitla (900 BCE–1521 CE), 44 kilometers from Oaxaca City, was a religious center for both Zapotec and Mixtec cultures. The archaeological zone is celebrated for its mosaic fretwork, a detail of which appears in Fernandez’s pigment print, and its stone columns supporting its central temple, that like Fernandez’s text and pigment print columns, support Bend. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, “Mitla,” Gobierno de México, accessed March 28, 2025,https://www.inah.gob.mx/zonas/zona-arqueologica-de-mitla. ↩︎

- “Composite: Three Conversations with Christina Fernandez” in Joanna Szupinska and Rebecca Epstein, eds., Christina Fernandez: Multiple Exposures (Riverside, CA: UCR Arts, 2022), 203. ↩︎

- When I use the term “ghosting,” I do not refer to the phenomenon of turning a cold shoulder on a friend, colleague, or contact. Instead, I reference a layering or palimpsesting of images, languages, and temporalities, arguably the exact opposite of the aforementioned (and possibly one way among many that our ancestors keep us company). ↩︎

- Roberto Tejada, National Camera: Photography and Mexico’s Image Environment (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009). ↩︎

- If anyone harbored lingering doubts about Fernandez’s investments in staging conversations between performance and photography, consider her 2024 curatorial work—the exhibition El Cuerpo: The (Performing) Body and the Photographic Stage at Gallery Luisotti (Los Angeles, CA), accessed September 28, 2024, https://galleryluisotti.com/exhibitions/el-cuerpo-the-performing-body-and-the-photographic-stage/Y. ↩︎

- Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, eds., This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (Watertown, MA: Persephone Press, 1981). When I speak of a “phantom citing,” I implicitly cite Rita Gonzalez, Howard Fox, and Chon A. Noriega, eds. Phantom Sightings: Art after the Chicano Movement (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), too, whose cover is graced with Fernandez’s “Lavandería #4” (2002). See also Tejada, National Camera. ↩︎

- Ethnic studies scholar Laura E. Pérez refers to this photograph by another title, “Christina: Self-Portrait,” in Chicana Art: The Politics of Spiritual and Aesthetic Altarities (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 130–32. ↩︎

- When I refer to “allegorical ruins,” I invoke a crowded force field of critical writing, including Walter Benjamin’s observations on German tragic drama (1928), The Origins of German Tragic Drama, trans. John Osborne (London: Verso, 1998); two essays from the early 1980s by Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism” and “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism, Part 2” in Craig Owens, Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture, ed. Scott Bryson et al. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 52-87; and cultural theorist Fredric Jameson’s far-ranging work, for example, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991). In the natural sciences, Brownian motion refers to the random fluctuating movement of small particles suspended in liquid or air that appear in collective formation to be in stasis, e.g., clouds. Here and elsewhere, I hear “Brownian motion” in connection with Latinx and queer studies scholar José Esteban Muñoz’s theorization of the “brown commons” in José Esteban Muñoz, The Sense of Brown, eds. Joshua Chambers-Letson and Tavia Nyong’o (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020). Enlivened by the congruence, I wonder, cloud-banking on Bend’s bends, What, after all, is dialectical synthesis, if not the very presencing, a repeat survivance, of Brownian motion? ↩︎

- Pérez, Chicana Art, 132. ↩︎

- A chronology of the work’s evolution can be traced through its varied installations, each affording another meta-bend in the project: At California State University, Northridge (1998), Bend was “set up on pedestals, with [different images from the] Ruin series photographs, measuring 20 × 24 inches propped on small tripod stands, each pedestal had a picture on it, and there was a lower pedestal, more like a table that had the self-portrait and the text . . . printed [out in black font] on one [white] page and laid out” (Christina Fernandez, personal communications with the author, March 10 and 11, 2025). Later at Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles (2014) and at the Palm Springs Art Museum (2019), Bend’s installation was ordered sequentially, one matted and framed referent after another: the wall text, the pigment prints, Self-Portrait, Dainzú, Cerro de la Campana (the panoramic photograph in the 2020 wall mural), and Mitla, all from the series Ruin (Christina Fernandez, personal communications with the author, February 23 and March 10, 2025). The final reorganized version of Bend, presented at Gallery Luisotti (2020), the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2023); the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2024); and forthcoming at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, consists of the insertion of the mural and the text, the latter split into two columns and rendered effervescent, and the centered, vertically oriented self-portrait, flanked by photographs from the Ruin series—the layout upon which this essay lingers. Once again, many thanks to Fernandez for taking the time to fact-check (across media platforms, including dormant email accounts) with me the details of Bend’s transformations. While the above differs from some published documentation of Bend to date, including what appears on Gallery Luisotti’s website, it accurately reflects the artist’s personal records of each version of the project that she graciously shared with me. Christina Fernandez, personal communications with the author, February, March, and April 2025. ↩︎

- The city of Huijazoo or Cerro de la Campana (300–800 CE) was the civic administrative hub of Zapotec civilization. Located thirty kilometers southeast of Oaxaca City, the archaeological zone is renowned for its monumental buildings, three colossal platforms, and funerary constructions, among them Tomb 5, replete with painted murals, glyphs, masks, and ceramic work,Sistema de Información Cultural México, “Cerro de la Campana (Huijazoo),” Gobierno de México, accessed March 28, 2025, https://sic.cultura.gob.mx/ficha.php?table=zona_arqueologica&table_id=213. ↩︎

Amy Sara Carroll’s books include SECESSION, FANNIE + FREDDIE/The Sentimentality of Post-9/11 Pornography, and REMEX: Toward an Art History of the NAFTA Era. With Electronic Disturbance Theater, she coproduced the Transborder Immigrant Tool and [({ })] The Desert Survival Series/La serie de sobrevivencia del desierto. Currently, she’s an Associate Professor of Literature and Literary Arts at the University of California, San Diego.

Cite this essay: Amy Sara Carroll, “Bend’s Bends: Christina Fernandez’s De- and Re-Materialization of Memory” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, April 28, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/bends-bends-christina-fernandezs-de-and-re-materialization-of-memory/