Decolonial Gestures and Entangled Forms: Elia Alba’s Migratory Aesthetics

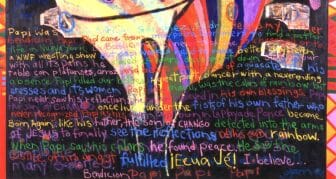

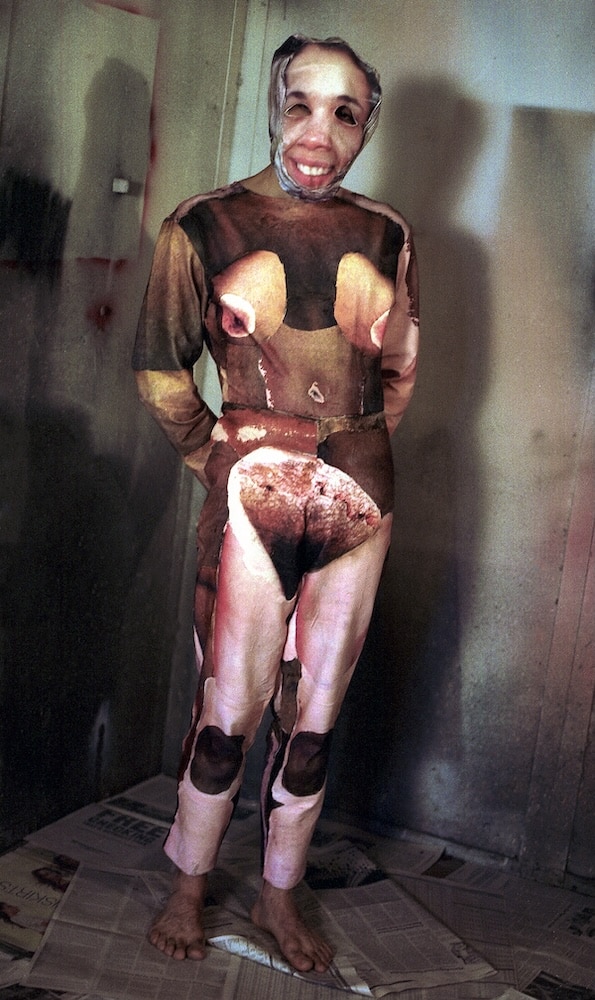

If I Were a . . . (2003) typifies the multilayered investigation into the migrant imaginary that has characterized much of Elia Alba’s varied artwork.1 During the four-minute film, performance artist Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful tries on three flesh-colored bodysuits adorned with a patchwork of photos showing Alba’s own body parts.2 Wearing an ill-fitting mask of Alba’s face, Raful moves, poses, and sways in front of a mirror. In so doing, he calls attention to the garments’ piecemeal design and to the feeling of watching and being watched.

Echoing the exhibitionistic body art of Ana Mendieta and the biomorphic surrealism of Wifredo Lam, Raful’s performance makes visible the historical contingencies and affective labor that surrounds notions of Latinidad. Alba enlarges and visually distorts each photo, forming a “variously shaded body . . . chaotically montaged into an uneasy union.”3 Suggesting multiple skin tones, the fabric collage indexes the diversity that flows in and out of Latin America as well as the broader hemispheric diaspora that connects to regions in North America. As Alba explains, “an elbow suggests Indian heritage, a knee for African, a shoulder for Spanish.”4

Alba’s bodysuits point to the “somatic othering” by which nations, prisons, militaries, and corporations deform, fragment, flatten, or commodify migrant bodies.5 Through quiltlike patches, the squares and circles of body imagery contain and separate this racial multiplicity, reminiscent of the Casta paintings of the Spanish colonizers.6 The Casta genre emerged during the eighteenth century in Mexico, then called New Spain. Through fictive family groupings, typically arrayed in sequential scenes, the paintings reinforced a gridlike hierarchy of classes, genders, and races to manage cultural intermixing and the threat of blurred social boundaries. Colorism and “pigmentocracy”—systems of racial classification that put lighter complexions at the top of the social order—persist throughout Latin American and in Caribbean contexts such as the Dominican Republic.7 In other words, the Casta’s grids evolved alongside more recent forms of identification, functioning as a container used to control movement, socially and geographically. Viewed from our contemporary moment of rising militarization and border security theater, Alba’s corporealized photo fragments become potent reminders that Afro Latinx, Indigenous, and queer/trans migrants’ subjectivities are targeted and monitored in documents like passports, residency papers, and visas under a xenophobic gaze.

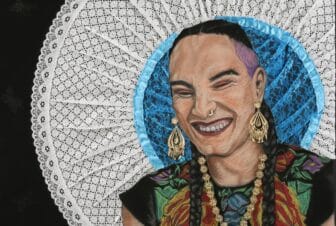

As an artist-curator-writer living in between the Dominican Republic and United States, Elia Alba (b. 1962) has dedicated her creative career to exploring how ideas of migration, race, and the body are entangled with regimes of coloniality, technology, spirituality, and the wider visual culture. Her interdisciplinary work spans a range of handmade artifacts and digital media, taking the form of dolls, heads, hands, masks, bodysuits, photos, installations, and fabric-based jewelry. Alba’s art serves as a material metaphor for, and spatial mapping of, the enduring impacts of colonial legacies on the movement and migration of diasporic people, while also acknowledging that migrant, Afro Latinx, queer/trans, and Indigenous populations experience harm in different ways.

While emphasizing that images heavily influence our perception of migration and play a decisive role in constructing imagined communities, Alba’s recent work on migration has developed a reparative direction, alongside her critical consciousness of obstacles to social mobility and movement. This is especially clear in her Hands series. Started in 2019, the series consists of soft sculptures and photographs of disembodied hands that use images of strangers, friends, and acquaintances transferred onto fabric. As in the bodysuits, the hands complicate narratives of race, identity, and belonging through tactile encounters with the body.

Alba states, “Utilizing the personal narratives of the sitters, along with historical and folkloric narratives I ascribed to them, I create a portrait of them through their hands.”8 This complex weave of history, myth, and Alba’s own visual iconography is visible in Cardinal and Gauntlets (2021).

photo transfers on fabric, glitter, acrylic, wire, polyester fill, zippers, acrylic box, 16 × 14.8 × 10 in.

Courtesy the artist.

The work relays the anti-blackness and phobia toward indigeneity that prevails in the Dominican Republic. Using images of a Dominican friend’s small hands, Alba inscribes a variety of drawings: The left hand features silhouettes of enslaved people, freed from their fetters, while a red cardinal appears on the right hand. The bird is symbolic of Alba’s father, a man of mixed racial heritage who became “Black” when he emigrated to the US in the 1950s.9 Alba is typically careful to balance the biographical details of her photographic subjects with broader themes. Rather than individualize the sitter by concentrating on their face, Alba uses their flesh—their bodily “gesture, the object[s] they hold, adornments, inscriptions or paintings on the skin”—to generate abstract, collectivistic portraits, capable of wider resonance.10

In the case of Cardinal and Gauntlets, a deliberately confusing syncretism practiced here fuses the stories of her father and the photographed body of her friend, as they are brought together to cohabit the same fleshy canvas. In undermining both the straightforward photographic indexicality of portraiture and any promise of stable identity for either individual, the work aspires to capture a more fluid set of experiences. It references, on the one hand, residual colonial hierarchies that cleave people apart based on gender, race, sexuality, and nationality; and, on the other, it evokes real and imaginative struggles against erasure and extinction that occur within migratory geographies tying together the Global North and South.

The presence of needlework in these pieces stresses the artist’s conceptual interest in fiber processes of repair, mending, and remediation. In Mexi-Samoa-Rose (2019), tattoo-like markings cover over the skin.

These markings reference the borders used to subdivide and enclose nations. At the same time, they also reference the counterhegemonic pathways forged by border-crossing outsiders, recalling Gloria E. Anzaldúa’s statement that the border “es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds.”11 As Alba explains, the sitter identifies not as a man or woman but as Mexican Samoan and belonging to a distinct third gender.12 Implicitly, Alba folds the lived experience of gender and sexual nonconformity into the work’s jagged, maplike designs and rough stitching. Containing sutures and scarification linked to the geopolitical order, each hand functions as what Susan Schuppli calls a “material witness,” referring to objects that can be “made to speak” the trauma and the resiliency that characterize global communities of color. 13

According to Rebecca Schneider, expressive movement in one’s hand and other body parts in the context of performance operates as a corposemiotic sign.14 Similarly, Alba treats the hand as a multitemporal, theatrical stage on which stories and signs of migration can be articulated, woven together, and shared publicly. As a consequence, individual works in the Hands series are not static objects. They can be (and often are) rearranged and recontextualized, opening up new mental associations and interpretative possibilities. For instance, the piece Ivan exists in multiple versions. Ivan Study #2 (2019) depicts a pair of hands resting flat on each other. Ivan Study #3 (2019) presents the same hands posed upright and clasping, each finger of one hand superimposed over the corresponding finger of the opposite hand, suggesting a fortress or shield. In Ivan Study #4 (2019), the palms of the hands are turned outward, revealing fistfuls of silk flowers with white, frilly petals.

Following Jacques Lacan and Edward Said’s insights into the unconscious, each version of Ivan draws attention to how our perceptions of the Other (whether they be friend, foe, foreigner, or lover) are always unstable. Existing not quite as photographs and not quite as standalone discrete sculptures, these hands retain indexical traces of real people and events, while also literalizing (in their physical variability) the contingencies of people who live between cultures, languages, and nations. Such migratory aesthetics reflect Alba’s own familial history of migration and creative labor, as her grandmother was a sewer and her mother worked in a jeans factory in New York.15

In Hold My Daisy (2019), a hand gently opens to reveal a small, white flower. The piece’s interrogative title and its urban backdrop (an asphalt ground with visible cracks) can be taken multiple ways. Alba considers it a playful portrait of friend and longtime collaborator, Kenya Robinson.16 At the same time, the play of formal relationships in the photo—including oppositions of softness/hardness, exposure/concealment, and impermanence/fixity—underscores the reality that diasporic subjectivities often exist in fragile precarity and uncertain relationship with the larger material and immaterial forces that cocreate them.

An open palm can signify trust, surrender, or reconciliation. But the daisy, as a member of the largest plant family on earth and found on every continent except Antarctica, forms a material connection to the web of life. Given the daisy’s medicinal status, its presence evokes the botánica businesses that sell herbs, candles, and tokens of saints and mythologic beings, providing syncretic continuation of homeland traditions for people living in diaspora. Interwoven layerings of ecology, corporeality, and curanderismo in Hold My Daisy activate the world-making power of Alba’s Hands, rooted in reparative principles of hybridity, impurity, futurity, and interconnectedness.17

In these works Alba mirrors recent theorizations that understand human migration as “constellation[s] of multiple belongings.”18 Shifting away from a model of the migrant body as an object surveilled and delimited within commercial or governmental coordinates, pieces like Hold My Daisy move us toward a more relational and speculative ontology that anthropologist Levi Vonk calls the migrant corpus.19 In this understanding, social and corporeal identities are conceived as pieces of a Deleuzian assemblage that is always in flux. The corpus is subject to questioning, reinvention, and recombination into new forms.20 By extension, Alba’s bodysuits, heads, masks, and hands function as fleshy props to assist in improvised performances of migratory multi-subjectivity, problematizing the colonial legacies that shape migration and movement while also helping to foster new images of relating and being in the world.

Endnotes

- Alba’s video If I Were a . . . is accessible at https://www.eliaalba.net/video/if-i-were-a-2003. ↩︎

- Alba writes, “These suits are digitally manipulated images of my own body, that were transferred onto fabric.” Modern artists such as Robert Rauschenberg used the technique of phototransfer to extend photographic imagery onto unconventional surfaces beyond the confines of the two-dimensional frame. In contrast, Alba’s use of phototransfer engages the struggles, experiences, and narratives of diasporic populations connected to the Caribbean, Latin America, and the Global South. ↩︎

- Eva Diaz, “Elia Alba: The Disguises of Identity,” Urban Latino, May 2005, 59. ↩︎

- Diaz, “Elia Alba,” 59. ↩︎

- Levi Vonk, “The Body Migrant: Border Militarization in Mexico and the Changing Migrant Body,” PhD diss. University of California–San Francisco, 2023, 3. ↩︎

- See Ilona Katzew, “Casta Painting: Identity and Social Stratification in Colonial Mexico,” New World Orders: Casta Painting and Colonial Latin America (New York: Americas Society Art Gallery, 1996), 1–39. ↩︎

- See Edward Telles, Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, Race, and Color in Latin America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014). ↩︎

- Elia Alba, from the series Hands (begun in 2019), Elia Alba, https://www.eliaalba.net/sculpture/hands-2016-2019. ↩︎

- Elia Alba, interview with the author, 1 July 2024. ↩︎

- Elia Alba, “Elia Alba: Hand Sculptures 2019–2022” (Unpublished catalogue, 2023), 2. ↩︎

- Gloria E. Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987), 6. ↩︎

- Alba, interview with the author. ↩︎

- See Susan Schuppli, Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2020). ↩︎

- Lucia Ruprecht, “In Our Hands: An Ethics of Gestural Response-ability: Rebecca Schneider in Conversation,” Performance Philosophy 3, no. 1 (2017): 111. ↩︎

- Elia Alba, “History, Memory, and Imprint,” Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 3, no. 2 (2021): 65–67. ↩︎

- Alba, interview with the author. ↩︎

- Alba resists the desire for purity, instead embracing the multiplicity of BIPOC diasporic communities, stating “I think when you look at my work, it really is about addressing the complexity of race and complexity of identity, which people want to put in a fixed place. . . . I don’t even believe people are fully one race or the other, even if they look it. There’s always other stuff going on.” Groana Melendez, “Interview with Elia Alba,” Baxter St. Camera Club of New York, https://www.baxterst.org/interview-with-elia-alba/. ↩︎

- Doris Bachmann-Medick and Jens Kugele, “Migration—Frames, Regimes, Concepts,” in Migration: Changing Concepts, Critical Approaches, ed. Doris Bachmann-Medick and Jens Kugele (Boston: De Gruyter, 2018), 8. ↩︎

- The concept of the “migrant corpus” is treated in the work of border anthropologist Levi Vonk. For more, see Vonk, “The Body Migrant,” 29-31. ↩︎

- Alba’s assemblage approach to migration and art making appears in her reflections on photography, as when she states: “Photography has always given us striking individual images, but it has also been a medium of combination.” See Elia Alba, “In between Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow,” Nueva Luz Photographic Journal 25, no. 1 (2021): 3. ↩︎

Benjamin Ogrodnik is Assistant Professor of Art History at Augusta University. His scholarship concentrates on global working-class visual culture, tracking how artists fight against oppressive systems and expand the possibilities of creative expression. His current project explores the convergence of environmentalism, border policy, and textiles in recent US Latinx art.

Cite this essay: Benjamin Ogrodnik, “Decolonial Gestures and Entangled Forms: Elia Alba’s Migratory Aesthetics,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, January 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/decolonial-gestures-and-entangled-forms-elia-albas-migratory-aesthetics/.