Turn away, towards, and unfurl: on the Work of Juan Sánchez

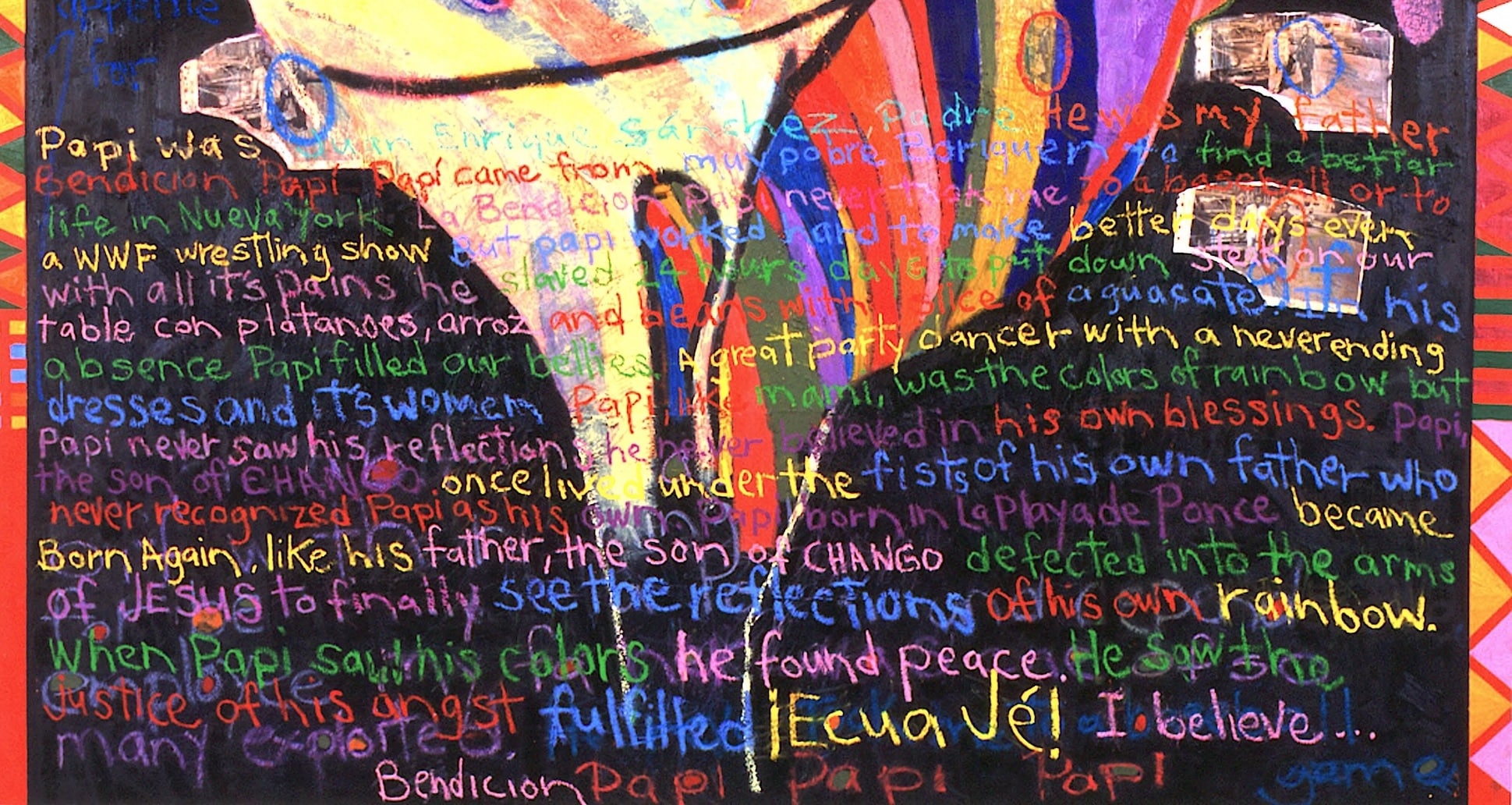

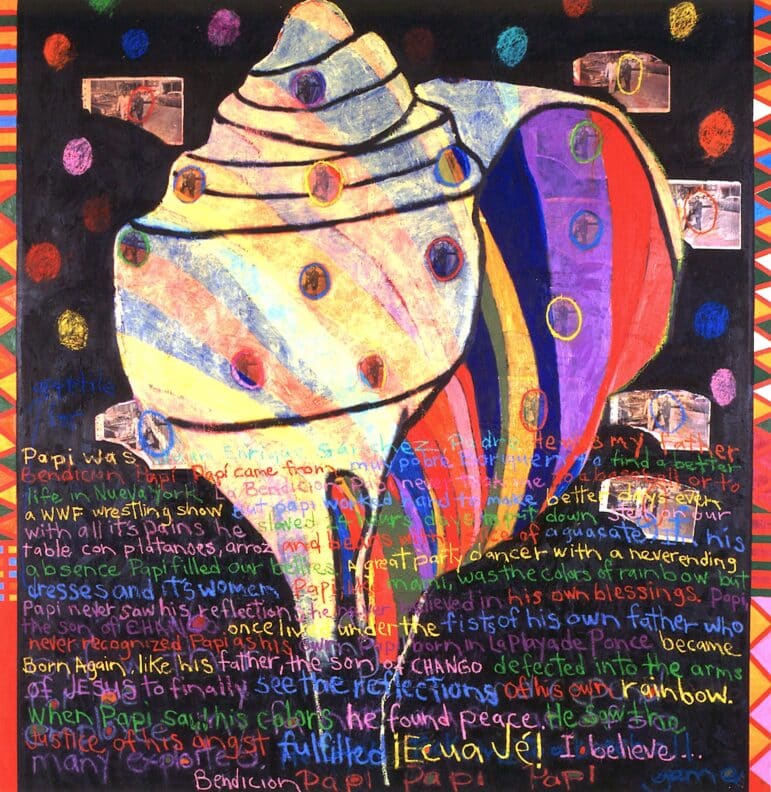

Across the lower half of Rainbow Shell, Reconciliation with My Father (1999), artist Juan Sánchez writes an emotive narration. A notably personal work in his greater politically committed practice, Rainbow Shell, Reconciliation with My Father (1999) showcases Sanchez’s signature mixing of painting, photography, and expressionist mark making to create multilayered works that relay the complexities of individual, collective, and cultural identity.

1999, oil and mixed media on wood panel, 74 × 72 in. Courtesy of the artist.

As a reader, one gets the sense that the text pours out of Sánchez in a stream of consciousness. As a viewer, the changing colors of each letter or word create a sense of dynamism. With each color change the text progresses as if to echo Sánchez’s father’s own spiritual progression:

Papi was Juan Enrique Sánchez, padre he was my father Bendición Papi Papi Papi came from muy pobre Borinquen to find a better life in Nueva York La Bendición Papi never took me to a baseball or to a WWF wrestling show but Papi worked hard to make better days even with all its pains he slaved 24 hours days to put down steak on our table con platanoes, arroz and beans with a slice of aguacate. In his absence Papi filled our bellies. A great party dance with a never ending appetite for dresses and its women Papi, like Mami, was the colors of the rainbow but Papi never saw his reflections, he never believed in his own blessings. Papi, the son of CHANGO once lived under the fists of his own father who never recognized Papi as his own Papi born in La Playa de Ponce became Born Again, like his father the son of CHANGO defected into the arms of JESUS to finally see the reflections of his own rainbow. When Papi saw his colors he found peace he saw the justice of his angst fulfilled. Ecua Jé! I believe . . . Bendición Papi Papi Papi.

Although not able to reconcile with his father during his lifetime, Rainbow Shell, Reconciliation with My Father is an ode, a way of making amends and returning to his father “the colors of the rainbow.”

Strikingly tender, Rainbow Shell, Reconciliation with My Father highlights certain formal and conceptual themes that repeat throughout Sánchez’s larger body of work. His large-scale multimedia paintings are often dedicated or pay homage to a figure of political or personal importance. In Rainbow Shell, Sánchez honors his father, his work ethic, his diligence, and dedication, while also holding his complexities. He is portrayed with dynamism. His evolution is at the center of Sánchez’s retelling, which culminates in a blessing.

Repeated throughout Rainbow Shell is a photograph of Sánchez’s father as a young man. He appears with his brother Rey, posing in front of his car on a sunny afternoon. Sánchez has isolated his father in each photographic print by drawing a circle around him with a different-colored crayons. This is secondary to the rainbow-colored queen conch shell that is the work’s central subject. The positioning of the conch shell, rather than his father’s image, at the center of the composition prioritizes a symbol of growth and renewal. The emphasis here is not a figure but a process—a reconciling of relationships of both Sánchez’s father with himself and Sánchez with his father. By foregrounding the queen conch shell, with its naturally occurring spiral, Sánchez finds a visual language expressive of a subject in continual change.

Historian Sebastián Robiou Lamarche discusses the significance of the spiral in Taíno cosmology and spirituality, noting its connection to creation myths and the cyclical understanding of time and existence. In these myths, the universe and life are seen as emerging from a series of meteorological cycles, reflecting an ongoing process of creation propelled by destruction and transformation. The recurrence of the spiral in Sanchez’s body of work signals a way of thinking that reverberates through his practice. Working against the static, settled, and linear, Sánchez attends to what transforms in and beyond the parameters of his canvas.1

The politically committed work that Sánchez is most recognized for, he notes, stems from his formative experiences of writing graffiti messages on the walls of his mainly Puerto Rican neighborhood in Brooklyn, where his parents settled after migrating from Puerto Rico in the 1950s.2 He recalls how the rallying cries he would write on the sides of buildings and bridges were often intervened with responses by other graffiti artists; as such, Sánchez drew inspiration from this process. As an artist he began creating canvases where photographic prints are densely layered with inscribed texts and hand-drawn symbols. His encounter with the graffiti scrawled atop densely layered poster advertisements throughout the city reminded him of abstract expressionist art and both, in turn, informed the improvisational approach that remains fundamental for him as an artist.3

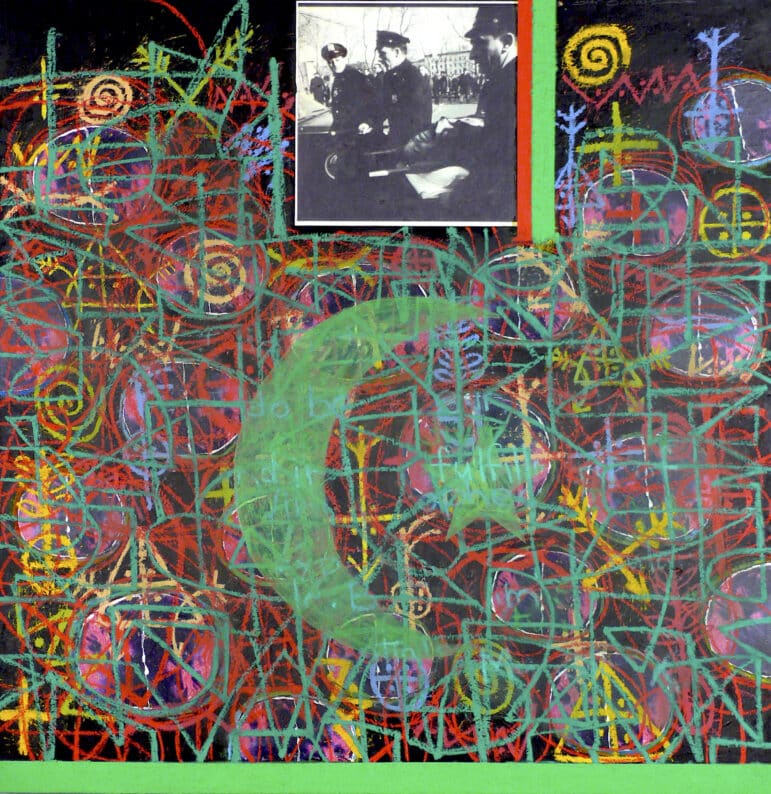

Sánchez’s similar techniques also create his expression in Cries and Wounded Whispers for Malcolm X (2001), part of an ongoing series of over forty mixed-media collage paintings on panel, Sánchez eulogizes the revolutionary leader by layering hand-drawn Taíno petroglyphs and symbols of Bantu origin across the composition, along with the crescent and star symbol of the Islamic faith.

oil and mixed-media collage on wood panel, 74 × 72 in. Courtesy of the artist.

With this artistic gesture, he links Indigenous, African, and Afro-diasporic belief systems with his own experience growing up as a member of the Puerto Rican and Black communities in Brooklyn, and having found himself at the intersection of various civil-rights struggles. Hybridity as conceptualized in the Spanish Caribbean as a myth of racial democracy, attempts to erase Indigenous and Black identities through a process of imposed homogeneity. In “Cries and Wounded Whispers for Malcolm X” symbols intersect. Markings are informed by adjacent signs. As with his spontaneous writing where he preserves grammatical errors intentionally, his dense layering of symbols can sometimes result in opportunities for meaning making and incongruences.

As a series, Cries and Wounded Whispers is a memorial to dissidents and martyrs, some well known, others less so. Among those honored are Mahatma Gandhi, Che Guevara, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, the Mirabal sisters, murdered by the dictator Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, and Neda Agha-Soltan, a student killed in 2009 during an election protest in Tehran, among others. Sánchez explains that the series title is meant to express how some of these figures have been recognized for their sacrifice while others have not, but whether their “cries” were heard “loud and clear,” or were “wounded whispers,” their dissidence resonates. He observes that it doesn’t matter how long ago these revered figures lived and died, the aftereffects and reverberations of their actions and death have bearing today, and will “generation to generation.”4

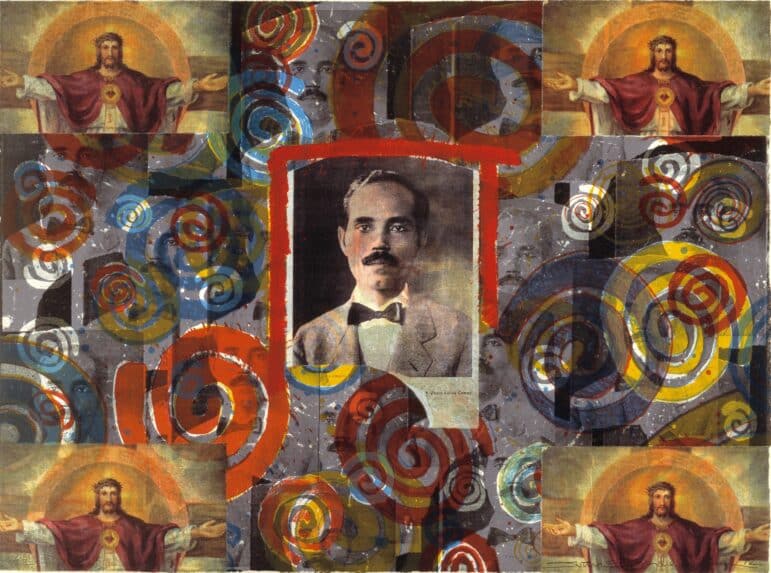

Sánchez’s skill in layering symbols to convey the complexity of his subjects’ identities is also fundamental to his printmaking practice. Para Don Pedro is an homage to the leader of Puerto Rico’s Nationalist Party and it exemplifies the artist’s approach to mixed media. The print is a combination of lithography with laser printing, hand-coloring, and collage. In the center is a color lithograph portrait of Pedro Albizu Campos, which is then repeated in the background layer in transparent black-and-white laser prints, on top of which Sánchez applies different-colored spirals drawn in oil stick. In each of the print’s four corners are collaged images of Jesus with outstretched arms acknowledging Albizu’s devout Catholic faith. The images of Jesus frame the composition and Albizu’s portrait and the Taíno spirals appear to emanate from the center, all presenting Albizu as a popular icon and martyr in the struggle for Puerto Rican independence.

22 1/4 × 30 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Don Pedro spent over twenty years in prison for conspiracy against the United States. While incarcerated he was subjected to torture, including exposure to harmful radiation, and he died shortly after his pardon and release. Albizu is remembered for his intellect and academic exceptionalism; he studied multiple disciplines and was a graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Law School.5 He is also remembered for his tenacity and steadfast belief in Puerto Rican independence. Sánchez’s print references Albizu’s devout Catholicism, acknowledging how his faith informed his nationalist views. The Catholic philosophical foundation for Albizu’s views, which ran counter to those of many of his contemporaries, is often viewed as a contradictory aspect of the leader’s thinking. Nevertheless, Sánchez notes that part of his intention was to portray Albizu “in a different light.”6

Sánchez underscores that in Para Don Pedro the spiral is meant to be a symbol of continuity, a “going through time” that allows for the persistence of political beliefs that move towards liberation. An inherent part of this process, he notes, is rethinking, reassessing, and re-interpreting. His portraits are not fixed unquestioning exaltations, but are rather thought of as processes.

With each homage, whether to his father, to the martyrs he holds in high regard, or to political leaders like Don Pedro, Sánchez leaves open the possibility that a historical narrative may shift, that new information might nuance our understanding of a historical figure. This, he notes, is central to the political project his work participates in, an additive process of continual unfurling. The grace he extends to his subjects reflects an understanding underscored throughout his body of work: identity, individual, collective, and cultural, is an ongoing emergence.

Endnotes

- Sebastian Robiou Lamarche, Diccionario taíno, documentado y comentado: Palabras indígenas de las Antillas Mayores, su significado e interpretación a través de la historia (pub. by the author, 2024), 38-46. ↩︎

- Mishkin Gallery, Artist Talk with Juan Sánchez and Christopher Rivera, August 3, 2023, 1 h. 37 min., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ABBeRttiOGQ. ↩︎

- Juan Sánchez, message to the editors, November 18, 2024. ↩︎

- Josh T. Franco, “Oral History Interview with Juan Sánchez, 2018 October 1–2,” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, October 1–2, 2018. ↩︎

- See Juan Palacio Moreno, “Myth & Remembrance: The Harvard Life of Pedro Albizu Campos,” Harvard Latin American Law Review 26 (May 2023): 302-325. ↩︎

- Juan Sánchez, interviewed by Alexandra Méndez, July 17, 2024. ↩︎

Alexandra Méndez García was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico. As an art historian her research focuses on the intersections of art and ecology. She holds an MA from the University of Texas at Austin where she studied at the Center for Latin American Visual Studies.

Cite this essay: Alexandra Méndez García, “Turn away, towards, and unfurl: on the Work of Juan Sánchez,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, January 15 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/turn-away-towards-and-unfurl-on-the-work-of-juan-sanchez/.