Diana Solís’s World-Traveling Creative Praxis

When photographer, illustrator, and painter Diana Solís (b. Monterrey, Mexico; resides Chicago) discusses living and working across Mexico and the United States, they explain that they stayed in Chicago because that is where they could do work they felt was necessary. Over four decades, Solís has devoted their photographic practice to documenting the lives, resilience, and resistance of Mexican, Latinx, immigrant, feminist, and LGBTQ+ communities in Chicago, especially in the once predominantly Mexican neighborhood of Pilsen, where for over four decades they have been a dedicated educator of young people and adults and community activist.1 Solís is also known for photographic work in Mexico City, where in 1982, for example, they documented the city’s fourth gay pride march.2 In one photograph we see a group of happy young marchers bearing flags of Grupo Lambda, one of three early lesbian and gay rights groups in Mexico. Leading the march, however, is a figure bearing a different mood, whose face is hidden beneath a red hood with cutouts for the eyes.

Courtesy of the artist.

from the series In My House, Chicago, digital color image. Courtesy of the artist.

As a photographer, Solís is sensitive in their approach to people who are apprehensive about being photographed. Ariel Goldberg has observed, for example, that Solís’s early portraits of friends in the lesbian and community in Chicago often, necessarily, obscured their subject’s faces, a reminder that whether in Mexico City or Chicago, people who came out in the 1970s and 80s did so at great personal risk. “Solís strategically found ways,” writes Goldberg, “to offer a record of energized gathering but respect the desire for anonymity.”3 A long trusted member of the community, Solís’s multidisciplinary work has secured their reputation as a “prominent figure in the cross-pollination of queer Latina visual and literary arts and organizing across the imposed US–Mexico border.”4

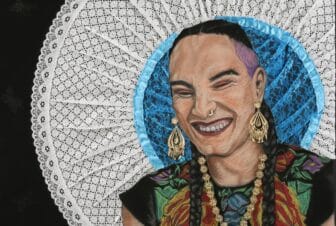

After two decades painting, making murals, printmaking, and creating illustrations for causes and organizations, Solís returned to photography in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, creating a deeply moving body of digital photographic portraits of the LGBTQ+ community in Chicago. In contrast to the earlier portraits of lesbian and gay activists, these digital portraits attest to a different moment in the history of being out, one of assertive visibility.

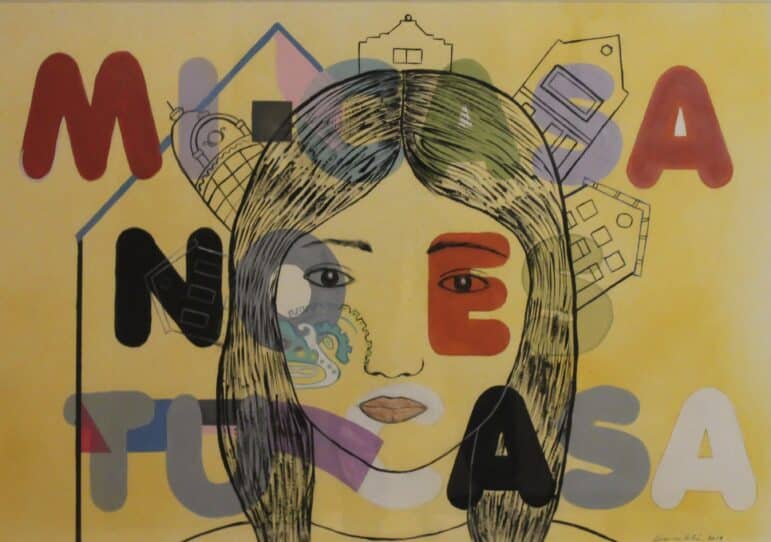

When we spoke in June 2024, Solís shared that their work in Chicago has often also focused on anti-gentrification community activism.5 We see this in their mixed media work Mi Casa no es tu casa.

The work shows a femme person against an array of tall narrow houses, each with a distinctive roofline conveying Pilsen’s urban texture. The houses create the effect of a crown around the figure’s head. Across the imagery, Solís has written, in bubble letters, “Mi casa no es tu casa.” Made with spray paint and acrylic on paper, the image and the letters call to mind the murals and graffiti tags that artist-activists have painted to assert their right to place, community, and culture. The layering of images and words serve to activate the image, as if the figure is thinking the words. Solís explains they made this work in “reaction to the saying mi casa es su casa (my house is your home),” an adage conveying hospitality and welcome. In the face of intense gentrification in Pilsen, however, Solís talks back, affirming instead: “my house is not your home, you can’t come here and take it away.” Pilsen was built by waves of immigrants, first Germans, then Czechs, then Italians, many of whom arrived to work in Chicago’s factories. By the 1970s the housing was run down but grassroots activists revitalized the neighborhood; by the 1980s Pilsen was a proud, majority Mexican and Latino community. Beginning in the 2000s the demographic makeup of Pilsen began to change again as more white and middle-class families sought out the neighborhood’s charm, but activists in Pilsen pushed back, founding organizations like Pilsen Alliance. Seen in this light, Mi casa no es tu casa is a testament to the history of activism in Pilsen, including their own history with organizations like Casa Aztlan and Mujeres Latinas en Acción.

Taking the femme’s crown as a point of inspiration, I recall the saying: “Home is one’s castle,” and how home is respite from being “out” in a hostile world. The image calls forth feminist philosopher María Lugones’s concept of world traveling, or how women of color, like the femme depicted in the poster, must “travel” at their own risk within “hostile White/Anglo worlds,” that inculcate them into feeling different, as if they don’t belong. But world traveling is also a mode of finding and making home and community. Lugones calls on us to seek out other women and communities of color, and to travel to find common cause, and to love across our differences.6

Lugones’s words describe exactly the kind of work that Solís has done throughout their decades-long career, forging connection to place by establishing friendships, building community, teaching, and asserting our right to reclaim space and celebrate love for chosen community and family. Solís’s creativity, whether in portraits like that of Moni Pizano Luna, who poses in a lovingly arranged domestic space with art on the walls, fresh and dried flowers, and a Mexican serape, or the femme figure who inspires action against the violence of gentrification.

Solís and I represent different generations of two different Latinx communities but we share the struggle and experience of gentrification and of being made to feel less than human. Born and raised in Chicago, I have seen immigrant communities and communities of color stabilize neighborhoods, only to lose ground to gentrification and so-called economic development. As a young college student I participated in the Puerto Rican community’s anti-gentrification activism in Humboldt Park. These personal reflections are inspired by Solís’s work and activism and their life experiences. Whereas Solís emigrated with their parents from Monterrey to Chicago as a child, my studies took me from my home in Chicago and my academic career led me to settle in southern Nevada; I am grateful to have been welcomed there by a generous community of artists of color, an experience that has enabled me to adapt the ethos I learned as a young activist in Chicago. Moreover, I am grateful that while some have questioned my making home elsewhere, my mother and grandmother did not; that experience resonates for me with another of Solís’s poignant portraits, this one of their mother and grandmother.

Abuelita Santos and Mom, Monterrey, N.L., Mexico

1996, gelatin silver print, Courtesy of the artist.

Here Solís’s mother stands to our right, with her arm around her mother’s shoulder, and she looks directly into the camera lens, meeting the artist’s gaze. Solís’s grandmother, on the other hand, crosses her arms and averts her eyes from the lens. A ray of diagonal light rakes across the grandmother’s body, which further serves to pull our eyes away from her, and back to the artist’s mother. It is easy to see where Solís gets their determination to be seen and to render those who might be erased.

When we spoke about the photo, Solís explained that their mother was very ill at the time of the portrait; she died about a year later.7 They shared that the illness may explain why she looks worn out in the photo and that their grandmother may have felt it inappropriate for Solís to take the portrait. Solís explains that still, they wanted the mother–daughter photograph because they understood that they didn’t know how much more time they would have together.8 Solís admits the photo was difficult to take.

It is this emotional complexity that is the hallmark of Solís’s work as a portraitist. The portrait conveys their investment in familial connection and in engaging the poignant ordinariness of intimacy and vulnerability. In conversation with Solís, I shared that I empathize: My grandmother didn’t like to be photographed and yet members of my extended family persisted during their last visits with her in Puerto Rico. They, like Solís, understood the imperative of documenting their intimacies, not least in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in 2017.

Throughout their creative practice, Solís has brought attention to communities that the neoliberal/neoimperial global economic order has relentlessly dehumanized. Their practice unsettles the prevailing Eurocentric definition of humanity as white, privileged, male, and heterosexual.9 Solís’s work, regardless of medium, elevates how, where, and with whom queer Latine folx find home, and how home, belonging, well-being, and intimacy are intrinsic to resisting invisibility. Solís invites us to consider the challenges, vulnerability, and urgency of documenting our joy and the tenderness of our intimacies. Given our current political moment, the urgency and the risks are real and Solís’s work exemplifies a refusal of hostility, echoing Lugones’s insistence on world traveling. The vulnerability and refusals that Solís’s work reveals show how many in the Latine and, more specifically, queer Latinx community often feel unsettled, whether in queer kinships, in the face of the mortality of the people and the precarity of the neighborhoods, cities, and regions that we love and call home.

Endnotes

- Ariel Goldberg, “Diana Solís; Intimacies in Resistance” Lucid Knowledge on the Currency of the Photographic Image (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2022), 218. ↩︎

- The first gay pride march in Mexico City took place in June 1979. See Edward J. McCaughan, “Art, Identity, and Mexico’s Gay Movement,” Social Justice 42, no. 3 (142), special issue: Mexican and Chicanx Social Movements (2015), 89–103, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24871328. Solís worked and studied in Mexico City from 1982 to 1985, communication from Solís to the editors, December 2, 2024. ↩︎

- Goldberg, “Diana Solís,” 218. ↩︎

- Goldberg, “Diana Solís,” 218. ↩︎

- Diana Solís, conversation with the author, June 2024. ↩︎

- Maria Lugones, “Playfulness, ‘World’-Travelling, and Loving Perception.” Hypatia 2, no. 2 (1987): 3. ↩︎

- Solís, conversation with the author, June 2024. ↩︎

- Solís, conversation with the author, June 2024. ↩︎

- See Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom,” New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (Fall 2003): 257–337. ↩︎

Erika Gisela Abad: Since 2019, Dr. Abad has examined Latinx representation across TV, literary works, visual & performing arts. She has been featured on Latinos Who Lunch, Art People Podcast, and NYU Latinx Intervenxions. Since 2024, she has been one of the Arts and Lit editors for Latinx Pop Magazine.

Cite this essay: Erika Gisela Abad, “Diana Solís’s World-Traveling Creative Praxis,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, January 15, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/diana-soliss-world-traveling-creative-praxis/↗