Two-Spirit Joy: Ester Hernandez’s Queer Portraiture

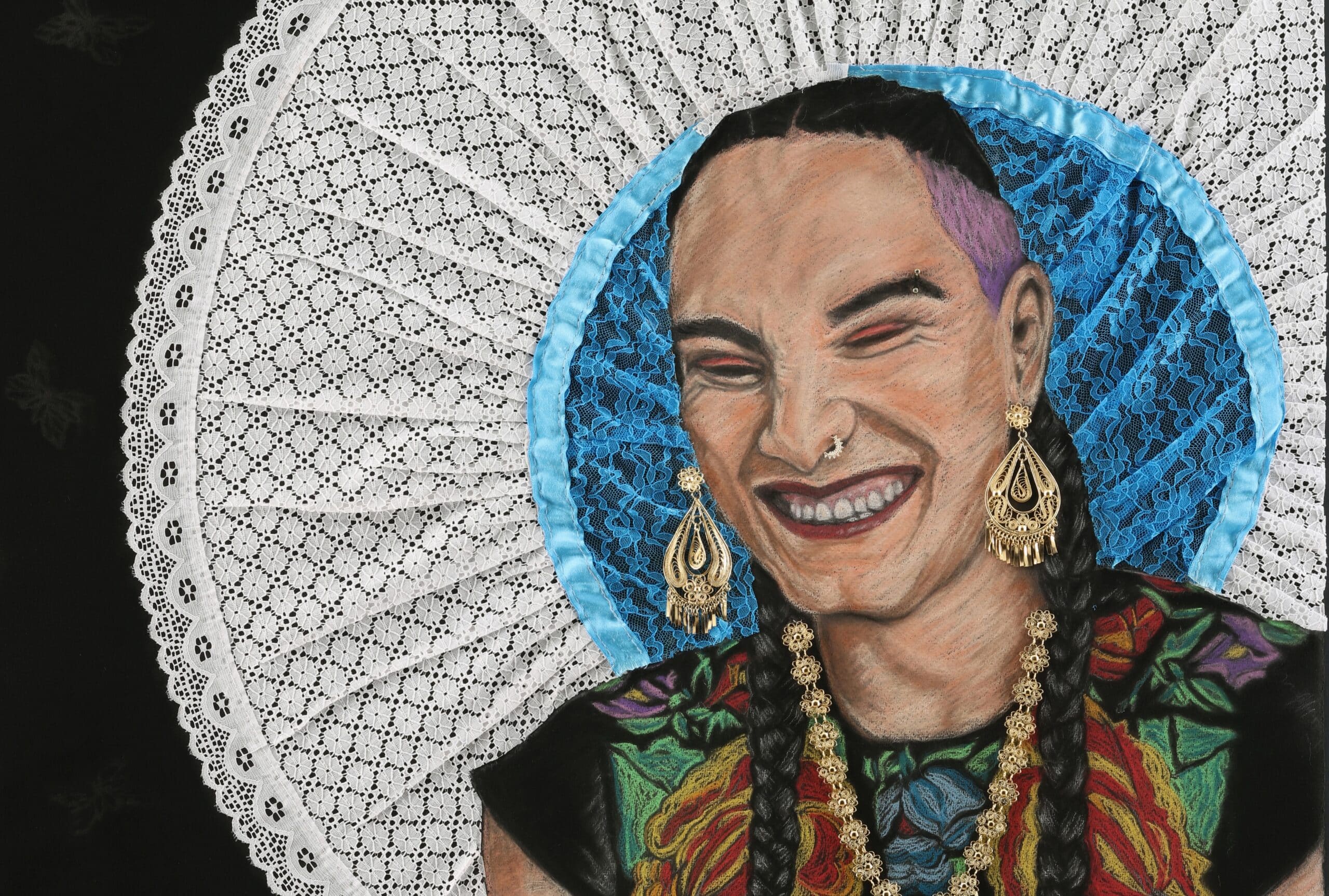

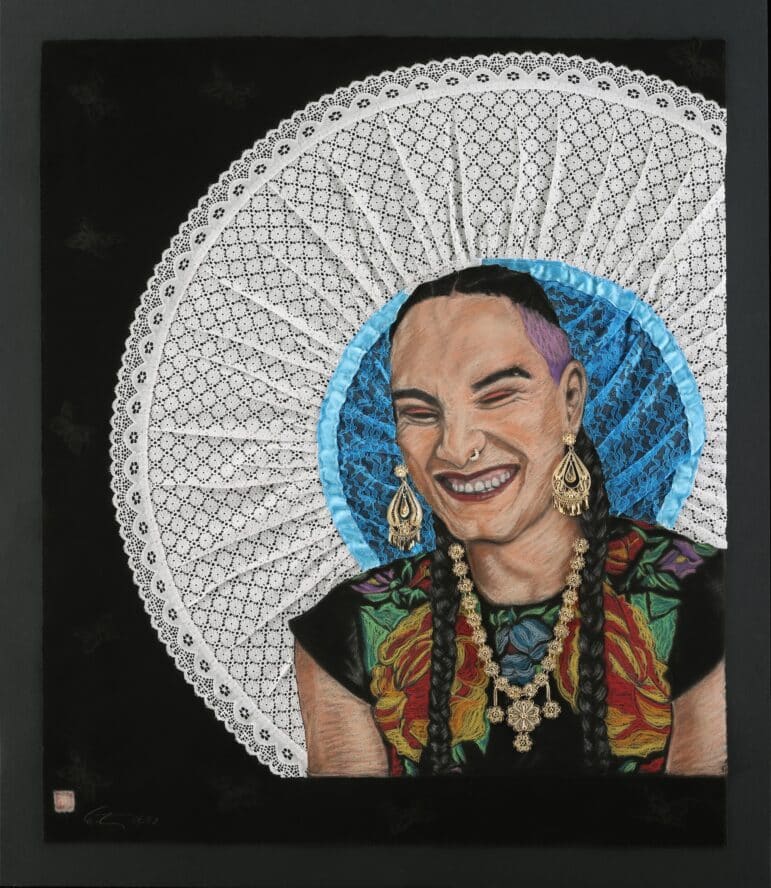

In her 2023 work Divina, La Muxe, Hernandez centers Indigenous trans joy as a central theme to her practice of uplifting radical figures. Based on her photograph taken at the Annual Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirit Powwow, Hernandez encapsulates the joy of a muxe, or a third-gender identity originating in Zapotec communities in Oaxaca, Mexico.

Employing mixed media, Hernandez overlays the traditional Tehuana headdress and gold filigree earrings, both originating in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Oaxaca, to replicate the experience and the regalia of woman-identified Tehuanas, including the trans person depicted by Hernandez. Divina, La Muxe continues the artist’s practice of queer portraiture and Indigenous community recognition, emphasizing the figure’s joy and smile as an act of trans resilience.

Courtesy of the artist

Joy, or gender euphoria, is a term that describes the “distress relief” and “positive emotions that can come from one’s gender/sex.”1 Divina, La Muxe visualizes trans joy through the figure’s gestures, posture, and likeness, particularly in the person’s facial expression. Hernandez’s interpretation reflects trans affirmation, positivity, and contentment, creating a unique Chicanx trans artwork that broadens the canon.

The portrait is an homage to the fluid nature of gender identity and the resulting joy in the safety of LGBTQIA2S+ community spaces.2 Divina, La Muxe represents the concomitant challenges, fear, and acceptance of both queer and Native identities that may appear to be fixed and quantifiable, which are reimagined and articulated in polyvalent ways through diasporic communities. This expression continues the lived experience of the Oaxacan culture through Hernandez’s lens, one that uplifts marginalized narratives and unveils the diverse influences that constitute and articulate Chicana/o/x art.

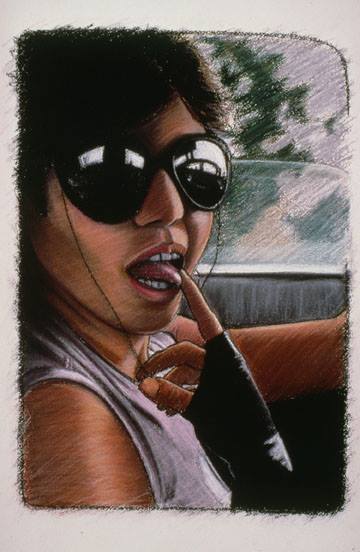

Hernandez has approached queer portraits with direct intimacy. In works like Renee, La Troquera (1985), and La Ofrenda (1988), she renders a past lesbian lover. Each Renee image affirms the personal connection the artist has with her subjects and the position she takes to use them as a substrate for themes of religion and gender.3

1994, pastel on paper, 30 × 22 in.

Collection of Dominica Rice Cisneros and Carlos Manuel Salomon.

Courtesy of the artist.

These images are seductive, exuding passion through their compositions. The sensual and overt sexuality defines these works, as well as their capture of the butch gender identity grounded in a presumed masculine of center (MoC) gender identity.4 With the exception of a few queer artists representing this community, it is rare in Chicana/o/x art for references to this gender identity.5 Hernandez expands on her longstanding commitment to including marginalized and underrepresented gender identities in Divina, La Muxe, with her rendering of the muxe gender. Muxe is a Zapotec word referencing a non-binary gender role recognized by the Indigenous Zapotec and is part of an “Amerindian gender system.”6

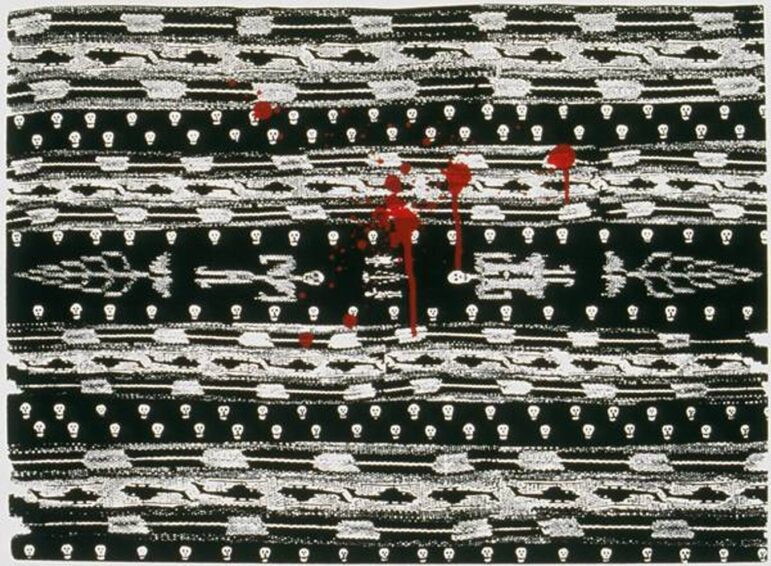

Hernandez identifies as Chicanx as well as having Mexican and Yaqui heritage. Therefore, her work consistently references ancient and contemporary Indigenous faith, culture, and activist perspectives. Her inclusion of the ancient Mesoamerican world with an emphasis on Movimiento advocacy and ancient goddesses continues the practice of Chicana feminists integrating intersectional forms of faith and spirituality. As scholar Laura Pérez has argued: “Chicanas were engaging the spiritual alongside more familiar areas of struggle (gender, sexuality, class, ‘race’) as another terrain upon which to challenge the cultural blind spots in mainstream values, in our assumptions and dismissals, in our pretensions to the universality and superiority of our beliefs, and in our antireligiosity or religious dogmatisms.”7 For example, Hernandez interlaces her veneration for Indigenous belief systems and iconography that employs the image of the Aztec goddess Coyolxauhqui in Luna Llena / Full Moon (1990), or contemporary Indigenous weavings in Tejido de los Desaparecidos (Weaving of the Disappeared) (1984), in which the weavings comment on US intervention in Central America. These pairings emphasize the resilience and strength of Central American Indigenous women’s communities in the face of political unrest and oppression.

The portrait of Divina, La Muxe stems from her encounter with her subject, part of Hernandez’s search for a native queer community since the 1970s.8 As a queer Indigenous artist, Hernandez was part of the emergent Gay American Indian movement of the 1970s and ’80s in the Bay Area. In 1974 Randy Burns (Northern Paiute) and Barbara Cameron (Lakota Sioux) founded the Gay American Indians in San Francisco to “serve the needs and interests of the gay American Indian community.”9 Among the challenges and intersectional oppressions impacting queer Native communities are queerphobias compounded by cultural differences unacknowledged by mainstream White queer communities. As a queer Native, Hernandez has long supported this movement, regularly attending the annual Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits (BAAITS) annual Powwow. This gathering is one of the largest two-spirit powwows and “exists to restore and recover the role of Two-Spirit people within the American Indian/First Nations community.”10 Powwows are ceremonial gatherings featuring traditional music and dances, including competitions that are gender specific based on dance category and regalia. In creating this unique powwow forum, the intertribal connection emphasizes the two-spirit, or those who have both feminine and masculine spirits.

1984, screenprint, 15 1/2 × 21 1/8 in. Courtesy of the artist.

In 2019, while Hernandez was at this gathering, she met her subject for Divina, La Muxe. For the first time in her portraiture, the connection between the artist and the sitter is not an intimate or familiar relationship, rather it was one of anonymous yet immediate, deep reverence. The artist recalls that it was a chance interaction when she came across her sitter and was “struck by this beautiful soul.”11 Her subject was clad in the traditional Tehuana regalia of an ornate lace headdress and embroidered floral huipil. When Ester met this person, she asked to take a photograph. The artist and la muxe discussed her experience emigrating to the US from Central America and their Maya identity.12 She articulated the necessity for a two-spirit community—given her depression and later suicide attempt—and the trepidation about being accepted into the Native space, let alone anywhere. She shared with Hernandez that she avoided smiling due to her queer presentation but that she had finally found a home in the two-spirit community. The personal narrative affected Hernandez, and she wanted to visually interpret the “joy of finally recognizing and acknowledging who we are and protecting that,” or the concept of gender euphoria.13

In developing Divina, La Muxe. Hernandez sought to crystallize both the power and beauty of queer, trans joy and her approach to pan-Native connections. As she explains, “the concept of borders doesn’t make sense to me, I believe in a world sin fronteras.”14 To translate these sentiments, Hernandez used her skill in the medium of colorful pastel on rich, black paper, as seen in works like Astrid Hadad en San Francisco (Astrid Hadad in San Francisco ) (1994). Her lustrous and masterful pastel handling in Divina, La Muxe beautifully delineates her subject’s identity. Whereas the portrait of queer cabaret performer Hadad uses frenetic linework to mimic the abundance of sound and movement, for Divina La Muxe, the artist’s geometric precision with the placement of physical material objects, including the delicate lace Tehuana headdress and gold jewelry, creates a culturally-grounded pan-Native portrait.

The artist sought authenticity through the use of mixed media elements. She asked friends to bring back a Tehuana headdress from Mexico, rejecting various versions. The filigree gold jewelry was sourced through a concerted search in jewelry stores in San Francisco’s Mission barrio, and she scoured several shops before finalizing her selections. The insistence on three-dimensional objects and the quality of these items was essential to capturing the nature of trans joy and gender euphoria, wherein a trans person crafts their aesthetic and gender in a bespoke outfit. The mixed-media objects’ depth and literal spatial projections spring forward, bringing forth the muxe. The effect creates a dimensional closeness to the muxe and mimics her own personal development in defining her gender presentation.

The material challenge of the mixed media application on the paper was the weight of the adornments. Hernandez had encountered this in a previous work, Don’t Mess with Lupita (c. 1986). The subject was a San Antonio–based drag queen known for her flawless opulence and theatrical flair. For this reason, her portrait warranted the extra bedazzled, lustrous layer of jewelry that Hernandez attached to the paper.

pastel on paper, with necklace and bracelet

31 × 22 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Divina, La Muxe became a passion project, with the artist immersing herself in the precise rendering of her sitter. Unfortunately, Hernandez does not know her muxe’s identity; as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, she lost touch with this person and has been unable to connect with her to show her the intricate portrait for final review. The figure’s anonymity perplexes both the artist and viewers, given the painstaking intricacy of the portrait.15 However, the work’s success rests in her sitter’s expression. The figure is enchanting and resplendent in her visage, and Hernandez brings this forth through the pastel portrait and the three-dimensional objects’ brilliant sheen. The portrait embraces this muxe’s personal journey of discovery, acting as an epiphanic snapshot of her figure’s realization that they, too, are entitled to experience unbridled joy.

Endnotes

- Will J. Beischel, Stéfanie E. M. Gauvin, , and Sari M. van Anders, (2021) “A Little Shiny Gender Breakthrough”: Community Understandings of Gender Euphoria. International Journal of Transgender Health 23, no. 3, 274–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2021.1915223. ↩︎

- LGBTQIA2S+ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and trans, queer and questioning, intersex, asexual or agender, and two-spirit. The plus sign + references any additional identities not encompassed by the current acronym’s characters. ↩︎

- Renee identifies as Chicana, Tohono O’odham, and Apache. Ester Hernandez, interview by the author, August 7, 2024. ↩︎

- As with any subversive term, there are multiple perspectives to a “butch” definition. See Caroline Berler, “Butches and Studs, in Their Own Words,” T: New York Times Style Magazine, video, 15 min., 11 sec., April 9, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/video/t-magazine/100000007075532/butches-and-studs-in-their-own-words.html. According to B. Cole, Masculine of Center (MoC) is “a term that recognizes the breadth and depth of identity for lesbian/queer/ women who tilt toward the masculine side of the gender scale and includes a wide range of identities such as butch, stud, aggressive/AG, dom, macha, tomboi, trans-masculine etc.” See B. Cole, “I am a Brown Boi,” Ebony, July 31, 2013, https://www.ebony.com/i-am-a-brown-boi-405/. ↩︎

- Chicana photographer Laura Aguilar’s series Plush Pony (1992) is a unique example of butch portraiture. Alma Lopez’s Chuparosa (2002) and Raquel Gutierrez’s Chromosomos (2012) feature the butch identity prominently. Both Lopez and Gutierrez’s prints were produced at the historic Self Help Graphics print center in Los Angeles. ↩︎

- Scholars emphasize that “muxe identity is less about sexual identity and more about Zapotec cultural categories and practices.” See Fabiano Gontijo, Bárbara M. Arisi, and Estevão Rafael, Queer Natives in Latin America: Forbidden Chapters of Colonial History (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2021), 21. ↩︎

- Laura Pérez, Chicana Art: The Politics of Spiritual and Aesthetic Altarities (Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2007), 3. ↩︎

- Hernandez’s involvement in the Gay American Indian movement has not been included in previous scholarship. Her distance from her own Yaqui history is challenging. Hernandez references this distance in her recent oral history: “Because as Amalia Mesa-Bains told me one time when I told her, You know, I don’t know so much about my—my Yaqui history—and I don’t know why. [And she said, Because it was dangerous to be a Native on both sides of the border.”] See “Oral history interview with Ester Hernández, 2021 November 15 and 17.” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. https://sirismm.si.edu/EADpdfs/AAA.hernan21.pdf ↩︎

- Randy Burns (Northern Paiute), “Preface,” in Living the Spirit: A Gay American Indian Anthology, ed. Will Roscoe (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988), 2-5. ↩︎

- Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits (BAAITS), “Mission Statement,” https://www.baaits.org/about, accessed June 20, 2024. ↩︎

- Hernandez, interview by the author, April 19, 2024. ↩︎

- The anonymous figure embraces the Zapotec culture’s muxe identity. While they do not, evidently, identify as Zapotec but instead cite their Indigenous heritage as Maya, this portrays the cross-cultural embrace of this figure to ground their gender identity in a form that best matches their self-identification. ↩︎

- Hernandez, interview by the author, 2024. ↩︎

- Hernandez, interview by the author, August 7, 2024. ↩︎

- Hernandez searched for her but only knew her previous stage name, “Chamul,” which had been changed since she completed the portrait. She is still searching for this person. ↩︎

Claudia E. Zapata (they/them) earned their PhD in art history at Southern Methodist University’s RASC/a program. They received their BA and MA in art history from the University of Texas at Austin. In 2023, the Blanton Museum of Art appointed them as their first associate curator of Latino art.

Cite this essay: Claudia Zapata, “Two-Spirit Joy: Ester Hernandez’s Queer Portraiture,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, January 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/two-spirit-joy-ester-hernandezs-queer-portraiture/.