Colonial Atmospheres: On Sofía Gallisá Muriente’s Celaje

- CELAJES

The Spanish word celaje moves in provocative ways. The Real Academia Española dictionary defines it as “the appearance of the sky when it is lined by tenuous clouds with different hues.”1 Older dictionaries provide more poetic definitions, describing it as “the color that appears and continuously varies at the extremities of clouds when the sun wounds [hiere] them and as the rarity or density of the clouds increases or decreases.”2 In its “cloudy” iterations, celaje points towards traditional signs of meteorological knowledge—the clouds—and displaces their familiarity, orienting us toward a weather turned strange, the heaviness of carbon-saturated clouds, and to the fiery hues of a wounded and infirm climate. What fascinates me about this word—uncapturable in the English cloudscape—is how its meanings proliferate beyond the clouds. Celaje can also mean skylight, an infrastructural element that can provide sun and ventilation or that can expose to elemental forms. It can mean a desire, or hope, or an aspiration, or a premonition. In Caribbean Spanish, it can refer to something that passed by in a flash, evoke the persistence of the past in the present and future, or, more simply, it can mean ghost.

Amid the compromised air of the COVID-19 pandemic, Puerto Rican artist Sofía Gallisá Muriente invokes the multiple resonances of celaje. Blending home movie footage from her grandmother’s archive with her own recordings in post-disaster Puerto Rico, Gallisá Muriente navigates the layered losses and accumulating catastrophes that have shaped the island’s atmosphere.3 Celaje (2020) weaves together scenes from an earlier period of the Commonwealth and its unraveling, inviting us to inhabit the haziness of a long arc of mirages, distortions, and obscured visions—what we might call the atmospheres of coloniality. Thinking atmospherically, the documentary film configures coloniality as both a mood and a mode of sensing—one entangled with loss, memory, and the ghosts left in its wake. Yet Celaje also moves beyond metaphor, drawing attention to the materially-altered airs we inhabit and the fragile conditions upon which collective survival depends.

- CLOUDED VISIONS: GHOSTLY ATMOSPHERES OF HOPE AND LOSS

Gallisá Muriente began developing Celaje to negotiate the gaps between her grandmother’s memories and her own. Through practices surrounding her grandmother’s recollections—repurposing her over-recorded cassette tapes, retrospectively filming her lived and affective geographies in Arecibo, Toa Baja, and New York—Gallisá Muriente initially attempted to grapple with personal and collective mirages, from the early Commonwealth middle-class aspirations to the unmasking of its promises in the present. But by the time she returned to finalize the film in 2020, waves of loss had come to pervade daily life across the Puerto Rican archipelago. Collective and personal losses compelled a deeper reckoning with grief. As a poetic voiceover reveals, Celaje became a meditation on impermanence, absence, and the many “leftovers, errors, and ghosts” that linger in the wake of everyday catastrophe.4 Processes of accumulation, her narrative also tells us, came to shape the film’s poetics. Through haunting soundscapes entangling industrial and biotic songs and through the distortions of her grandmother’s over-recorded tapes, Celaje immerses us in a sonic haze where historical and environmental processes—and their residues—reverberate.

Reading from the poetic introduction of Cómo se formó Puerto Rico (How Puerto Rico was formed)—a popular education book published in 1968—Celaje begins with erosion and sedimentation as the elemental origin story of Puerto Rico’s emergence. Entangling geological time with the archipelago’s historical time, the film drifts through scenes of everyday care in her grandmother’s life: brushing her hair, applying lipstick, taking medicine, or tenderly smiling into the camera. These moments unfold within her grandmother’s home in Levittown—a planned community developed in 1963, embodying a middle-class life imagined during the Commonwealth’s early modernization promises. These tender scenes of domestic inhabitation are delicately interwoven with glimpses of Puerto Rico’s urban landscape. Caravel souvenirs, shopping malls, General Motors logos, and monuments to Pedro Albizu Campos all form a constellation of fragments that configures the archipelago’s urban and affective landscapes.5 Silence brings us to witness the footage of a funeral, uniting personal and collective grief. And, in the murky visions of an automotive tour, Celaje proceeds to take through the island’s natural, built, and hybrid landscapes—sparkling salt ponds, electric plants, empty post-hurricane houses. Gallisá Muriente turns the island’s erosion into a poetic meditation through blurred and blurring processes of ruination and possibility that emerge under the shadow of colonial storms.6

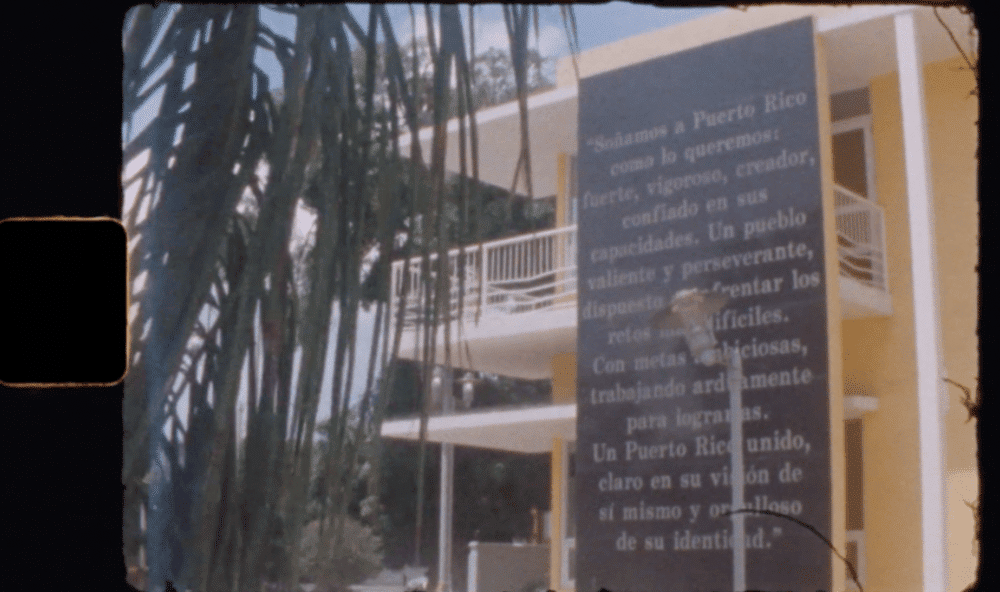

Through personal and collective memory, Gallisá Muriente negotiates the conditions and limits of remembrance. Suspended between her grandmother’s everyday life and Puerto Rico’s mnemonic landmarks, the film poses a quiet but urgent question: What can be recorded and what precipitates out of memory? By placing caravel souvenirs alongside scenes of intimate, everyday life, Celaje exposes the banality of state-sanctioned memory and the silences left in the afterglow of neocolonial cruel hopes. Its grainy, low-definition textures filter these tensions through a persistent fog—a “clouded vision” that hovers over Puerto Rico’s lived experiences. Dreams of sturdiness and vigor, as a plaque in Guánica’s City Hall proclaims, are revealed as collective mirages whose unveiling is never fully achieved. Yet Celaje does not seek to recover these promises. Instead, it proposes a different mode of sensing that is attuned to the perceptual worlds that emerge when we “stay with the trouble” of coloniality’s haze.7

- THE HEAVINESS OF ATMOSPHERES

Celaje’s memory work is interested in notions of ruination and erosion as the undercurrent of the Commonwealth. But the film also moves beyond metaphor, attending to material conditions of what Farhana Sultana has called “the unbearable heaviness of climate coloniality.”8 This notion speaks to the disproportionate burden climate change places on precarized communities across the Global South, and to climate as a lived experience—one that accelerates both social and environmental erosion. Coastal erosion frames Celaje, not only thematically but materially. The heaviness of the atmosphere saturates the film’s textures, shaping its mood, its politics, and sensoriums.

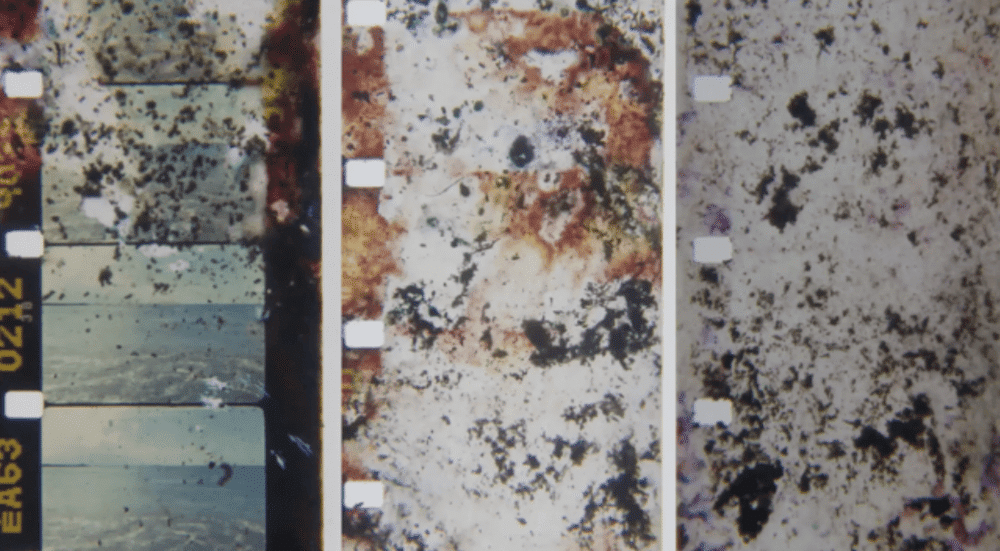

Within the precarities shaped by ongoing blackouts and the air’s saturation with humidity and saltpeter in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, Gallisá Muriente turns to the chemistries of film as another meditation on impermanence—this time, through the materiality of film amidst dense atmospheres. Positioning degradation as both destructive and creative, Celaje is submerged in local elemental milieus and coproduced through unpredictable processes of oxidation and fungal overgrowth. These processes interrupt the transparency that we have come to expect from film, offering us instead opaque, clouded, and eroded images—celajes that unsettle illusions of permanence through records of processes often vanished from the medium. As a petrochemical and mineral assemblage, film itself is implicated in fantasies of insulation and durability. These eroding visions render the medium a record of erosion and fragility inseparable from the atmospheres where it is emplaced.

While Celaje emerges from the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Maria and COVID-19, it is not bound to a single event, nor solely to the ephemeral. Instead, her memory work conjures the cumulative atmospherics that have long shaped life and breath in Puerto Rico. Her engagement with corrosion, humidity, and heat—and the murky, devoured images they produce—resonates with a deeper history of enduring atmospheric weight. Celaje decenters the spectacle of the storm, aligning instead with works like Beatriz Santiago Muñoz’s 10 Years/Long Exposure (2014), an installation attuned to coloniality’s enduring airs. With photographs salvaged from the ruins of the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station, 10 Years/Long Exposure figures coloniality as a slow aerial decomposition inscribed not only in our carbon-saturated present, but in the long histories of military violence that have shaped Puerto Rico’s relationship to air. These are records of a slow debilitation—of an air that clings rather than clears, of imposed endurance, and of catastrophic exposure that renders both body and land infirm. They register the ongoing heaviness of atmospheres pressing on ordinary life.

- SHARED AIRS

Within heavy atmospheres and clouded visions, what forms of politics might emerge? Attending to celajes—those fleeting, obscured layers of the visible—offers a way of surfacing unseen realities, revealing an air inhabited by myriad presences with whom we share our most vital medium. Air dispels the fantasy of individuality and impermeability, compelling us to reject the colonial separation between humans and the milieus that envelop us.9 As Timothy Choy and Jerry Zee remind us: air gathers us together.10 Near the end of Celaje, Gallisá Muriente films her mother playfully interacting with the sensitive plant mimosa pudica, known in Puerto Rico as moriviví—I lived, I died. Beyond its gentle playfulness, this moment opens onto something else: a politics of vulnerability, a shared sensitivity attuned to the fragile conditions of collective human and more-than-human survival.

Endnotes

- Diccionario de la Real Academia Española, online version 23.8, s.v. “celaje,” accessed June 30, 2025, https://dle.rae.es/celaje. Author’s translation. It is important to note that normative dictionary definitions oftentimes exclude vernacular polysemy. For example, the uses of celaje in the Caribbean are excluded from the RAE’s list of meanings. ↩︎

- Pedro Martínez López, Novísimo diccionario de la lengua castellana (1854), s.v. “celajel.” Author’s translation. ↩︎

- Yarimar Bonilla and Marisol LeBrón suggest that Maria revealed the longue durée of such accumulations. Disasters, they tell us, are “cumulative and ongoing” in Yarimar Bonilla and Marisol LeBrón, “Introduction: Aftershocks of Disaster,” in Aftershocks of Disaster: Puerto Rico Before and After the Storm, eds. Yarimar Bonilla and Marisol LeBrón (Haymarket, 2019), 15. ↩︎

- In a voiceover in the film, Gallisá Muriente is heard saying, in Spanish, “Esta película está hecha de sobras, errores, fantasmas,” (23:09-23:15). ↩︎

- Pedro Albizu Campos (1893-1965) was a leading figure in Puerto Rico’s independence movement. He was the president of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico and one of the leaders of the Nationalist Uprising in 1950. Given his opposition to the Commonwealth, he was imprisoned multiple times, spending a total of twenty-four years in prison throughout his life. The inclusion of footage of a commemorative bust in Celaje is not concerned with a narrative of heroism, but rather points towards the affective landscapes within the neocolony’s cumulative turbulences. ↩︎

- This phrasing is inspired by Malcom Ferdinand’s “colonial hurricane,” a term that urges us to consider climate histories within the long arc of colonial histories in the Caribbean. See Malcom Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World (Polity, 2022). ↩︎

- Feminist science scholar Donna Haraway uses “staying with the trouble” as mode that refuses transcendence and compels us to work within the troublesome spots of the colonial Anthropocene. See Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016). ↩︎

- Farhana Sultana, “The Unbearable Heaviness of Climate Coloniality,” Political Geography 99, (2022): 3. ↩︎

- My reading here is indebted to Stacy Alaimo’s work on exposure and transcorporeality, a method that works through permeability and vulnerability in contrast to masculine mastery. See Stacy Alaimo, Exposed: Environmental Politics and Pleasures in Posthuman Times (University of Minnesota Press, 2016). ↩︎

- Timothy Choy and Jerry Zee, “Condition-Suspension,” Society for Cultural Anthropology 30, no. 2 (2015), https://doi.org/10.14506/ca30.2.04. ↩︎

Maria Zazzarino is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at UC Santa Barbara. Her research explores extraction and environmental aesthetics in Caribbean literature and visual culture. She curated Donde cruzan los humos espero una semilla (La Casa Encendida, 2024), an exhibition on global fossil aesthetics and the impasses of the present.

Cite this essay: Maria Zazzarino, “Colonial Atmospheres: On Sofía Gallisá Muriente’s Celaje,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, August 4, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/colonial-atmospheres-on-sofia-gallisa-murientes-celaje/