Death & Ambition in Vincent Valdez’s Art

What belongs to you? It’s a major question elicited by the painting It Was Nevers Yours by Vincent Valdez.

To even begin to address this, a cascade of other questions come to mind: Why do you think it belongs to you? What does belonging or possession mean? When I ask myself these questions, I quickly arrive at something fundamental, at something concrete and daunting. It’s an analysis that requires a brutal clarity and honesty. To enumerate your desires and belongings is one thing—to understand where they come from is its own mountain. It might feel easy to say that those things that feel most inherent and fundamental to us, motivations, desires, culture, identity, are unique and ours alone to shape and use. The title of Valdez’s painting, however, whispers its implication with devastating clarity: it never belonged to you, none of it ever did. It’s so defiant that in its most expansive form, it leaves me with the sensation of being confronted with a dramatic, unavoidable destiny.

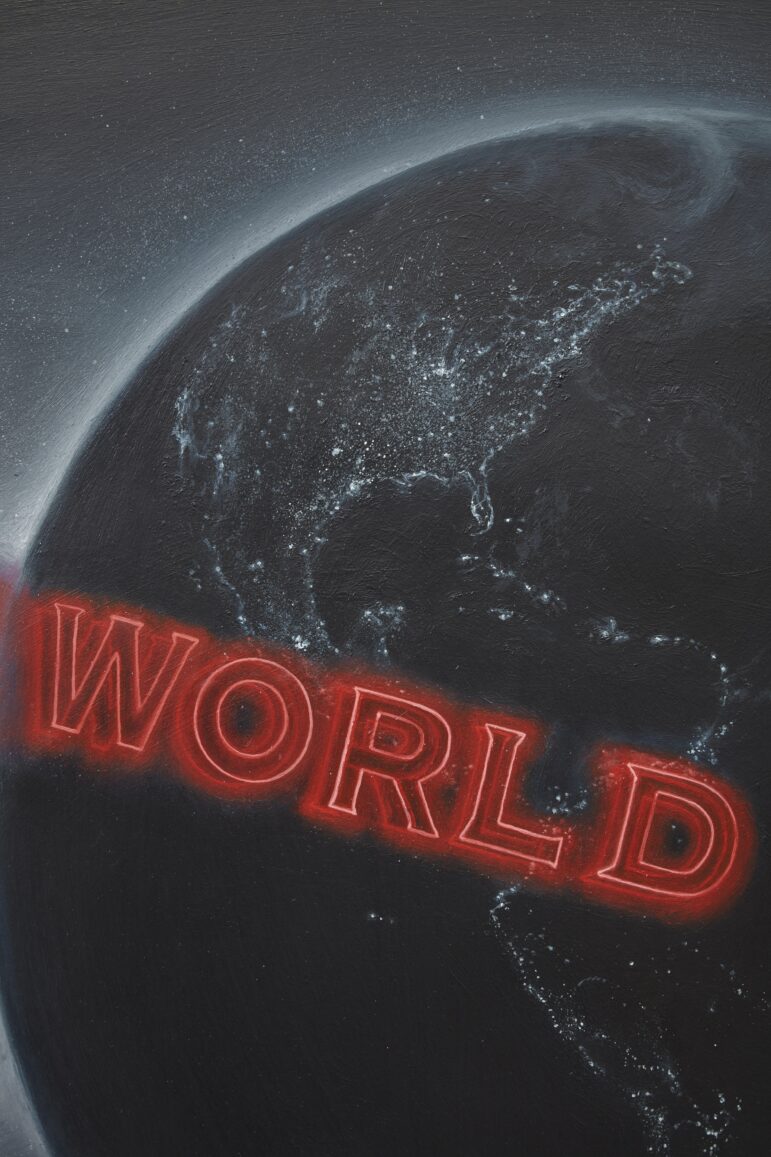

In this work, Valdez paints a view of Earth from outer space with blues, blacks, and hints of magenta. It’s a cold rendering of the planet, almost spectral. Save for the lights from our electrical grids, the Earth feels abandoned, if not devoid of life. The beckoning tendrils of space’s vacuous arms are ready to hold it in an imminent, chilling embrace. Foregrounding all of this, wrapping around the planet like it was a simple advertising pole or a vintage diner, is a popular phrase in neon-red lettering: “The World is Yours.”

Perhaps this phrase is familiar—maybe Nas’s song comes to mind.1 Both Nas and Valdez openly borrow this phrase from the cult classic film Scarface.2 In its cautionary tale, Cuban exile Tony Montana has migrated to the United States to pursue the capitalistic American dream—the movie makes explicit that Montana is viciously anti-communist, not a surprise for a movie made in 1984. Frustrated with his menial job as a dishwasher, Montana enters the drug world and rapidly ascends it, powered by intensity and ambition. The declaration “The world is yours” is deployed twice in the film, both times in reference to the American Dream—highlighting the ruthless ambition required to achieve it (Tony taking over Frank’s operation) and the grotesque depths that bring about its dark consequences (Tony’s opulently violent death).

Valdez’s work asks us to take a beat here. The declaration’s presence in the painting might make us think it is aimed at white US Americans. Perhaps “this land was never yours” registers as a counter to Manifest Destiny. But what if the title is aimed at people of color? By leveraging the film’s themes via the phrase it popularized, Valdez tasks viewers to consider their ambitions against the consequences This assertion feels clear in Valdez’s painting, possessing an irreconcilable tension and causal link between the cold, lifeless world that seems nearly blinked out of existence, and this statement of individualistic ambition: “the world is mine.” It creates room for pause, if not critique—is the cost of individualistic ambition and achievement a lifeless planet?

Moreover, for the black and brown people that the foundation of the United States and its economic-material ambitions transformed into the less-than-human, having been devasted by disease, killed for sport, enslaved to mine precious metals or cash crops, made to make homes in inhospitable places, in the irradiated sites, in the swamps, in the discarded afterthoughts of whiteness—do our desires for achievement bring us closer into proximity with the mobilized white desire that devastated us?3 Are these ambitions compatible with our histories?

Today, with so many more people of color in positions of power in America than ever before, there still have not been fundamental changes to institutions and corporations, and moreover it’s clear that we are capable of replicating the same power structures and dynamics of white supremacy. The myth of American exceptionalism and self-possessed individualism can take the form of American ethno-narcissism, creating the dangerous belief that holding a marginalized identity, such as Latinx, means that we are exempt from critique or that our sheer existence is resistance. Without critical apparatuses with which to inspect the world we live in, identity as a reliable way to measure political and ethical commitments is simply naive. Like Tony Montana, we stand to psychically implode on ourselves and betray an ethic that made us stand counter to the dominant white power structures and ways of ordering the world. In the context of Black Americans, thinkers like literary critic Hortense Spillers also agree: “I know we are going to lose this gift of black culture unless we are careful. . . . Now we’re the head of international courts, president of the United States, sitting on the US Supreme Court, presidents of universities, CEO of American Express. You name it, some black person is it. But the price of that, is to lose this precious insight that connects you to something human. . . . We’re losing that connection.”4

Valdez invokes these questions in beautifully painted work, with meticulous brushwork that belies potentially devastating themes. This tension is central to Valdez’s modus, a productive dynamic he also uses in an in-progress painting of the killing of Jose Campos Torres titled The Hole. On May 5, 1977, the twenty-three-year-old Army veteran Campos Torres was arrested by Houston police for getting into an altercation at a bar. He was taken to “the hole,” a spot where Houston police officers would beat detainees out of sight of potential witnesses. After brutally beating him they attempted to have Campos Torres booked, but his injuries were so extensive that their supervisor demanded they take him to the hospital. The arresting officers then took Campos Torres back to “the hole,” perhaps for more violent abuse, and then tossed him into the Buffalo bayou, under the fantastically cruel and unrealistic assumption that he would swim. Campos Torres died in the bayou and his body washed up to the banks three days later.5

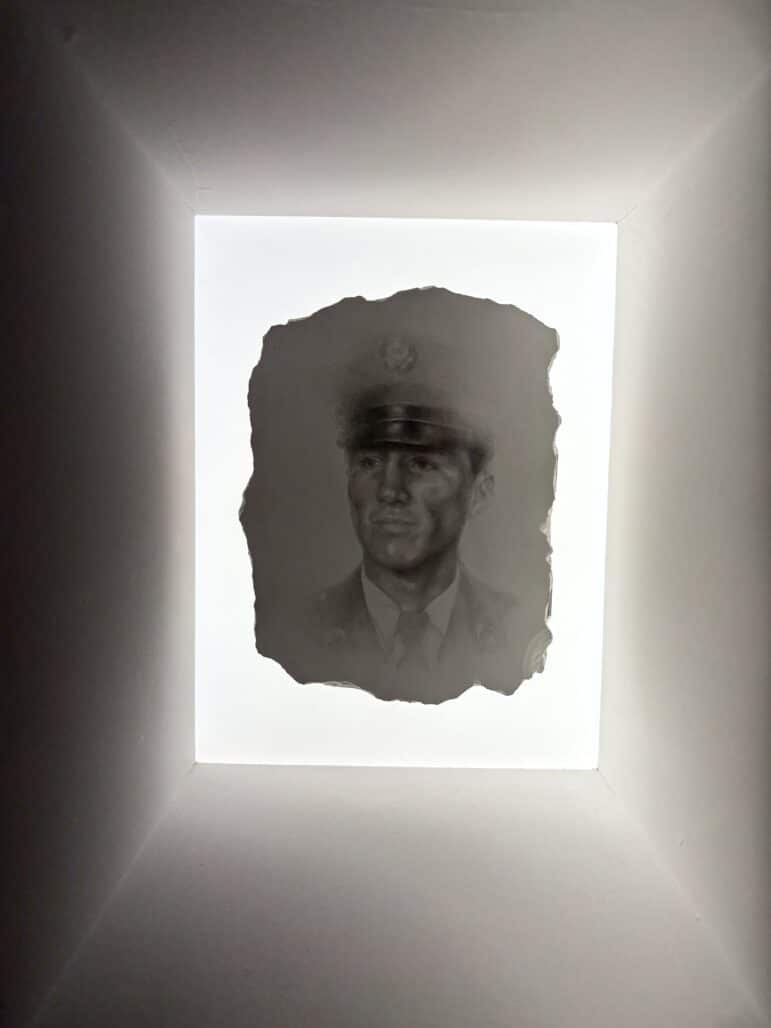

Valdez’s monumental canvas seems to take place at sunrise or sunset, when one is most aware of time’s passing and its ephemerality. Instead of showing us any other possible scene from this event, of a physicalized dying of Campos Torres, Valdez paints the moment when divers are jumping off a tourist boat into the bayou to search the waters close to where Torres’ body was recovered. This potent return to the site of past trauma and violence visually materializes the site of Campos Torres’ drowning and the site of direct violence committed by officers of the law. The murky waters of the bayou take up most of the canvas, painted in muted and calming blues and greys. Valdez skillfully renders the shimmering waters, creating a scene so beautifully benign, almost banal, that it could be confused for a tourist outing rather than the site of a violent murder.6 The focus on the water obfuscates the trauma and violence that this water holds in its past, where water filled Campos Torres’ lungs and ultimately asphyxiated him.7 Here, Campos Torres is an absent presence, a strategic decision made clearer by a pendant portrait in Valdez’s retrospective at CAAM Houston, where he memorializes him as the Army veteran.

Valdez is deeply interested in unearthing these histories to create confrontation, a moment of eruptive possibility, a site for unsettling the ground we stand on.8 As he states, “my aim is to incite public remembrance and to counter the distorted realities that I witness, like the social amnesia that surrounds us all.”9 His work underscores that to understand our place in the world, we have to know what our past holds. This takes on ever more importance in context of contemporary loss—loss of memory in the forms of redevelopment and gentrification, loss of community, elders, and stories. The rapidly moving world of the digital age demands a resistance to go slow, to cruise, to wade, to sleep and dream.

Endnotes

- Nas, “The World Is Yours, October 5, 2015, music video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_u6mqary2A. ↩︎

- Nas, “The World Is Yours.” Genius, About section. https://genius.com/Nas-the-world-is-yours-lyrics; and, Brian de Palma, Scarface. 1983; United States: Universal Pictures. Vincent Valdez, email exchange with the author, April 5, 2024. ↩︎

- This line of thinking is fundamentally informed by Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 13-31. ↩︎

- These words are spoken by Spillers in Arthur Jafa, Dreams Are Colder Than Death, 2013, video, 52 min., 57 sec. ↩︎

- Jesús Jesse Esparza, “Torres, Joe Campos,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed November 01, 2024, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/torres-joe-campos. ↩︎

- This line of thinking emerges from Professor RaMell Ross’s notion of the “epic banal”, a strategic depiction of marginalized people in their everyday-ness as an agentic counter-measure against sensationalist, muscular, and straightforward imagery of them. He discussed this in his photography courses at Brown University, Ross, VISA 1520: Digital Photography course, (Brown University, Providence, RI, Fall 2018). ↩︎

- Joe Campos Torres’s murder, among a variety of other factors, galvanized the Moody Park Riots in 1978, an important event in Houston history. For more on the event and its impact, see Robinson Block, “Moody Park: From the Riots to the Future for the Northside Community,” Houston History Magazine, November 2012 ↩︎

- Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes. ↩︎

- Vincent Valdez,” U.S. Latinx Art Forum, https://uslaf.org/member/vincent-valdez/. ↩︎

Jorge Eduardo Sibaja (Bene Xhon) was born and raised in Los Angeles and is currently a curatorial assistant at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University. He studied Art History and Economics at Brown University. He is interested in sound, indigeneity, and locality.

Cite this essay: Jorge Eduardo Sibaja, “Death & Ambition in Vincent Valdez’s Art,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, January 15 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/death-amp-ambition-in-vincent-valdezs-art/.