Adriana Corral’s Sous Rature, “Under Erasure” (2016) and Unearthed: Desenterrado (2018)

In Adriana Corral’s site-specific installation Sous Rature, “Under Erasure,” there is a visual trick at play. Approaching the work on the floor of the gallery, one sees a three-inch line of gray concrete that serves as an edge, an adult-sized gaping hole that summons viewers forward, without customary formalities; there they encounter the cross-section of the natural sedimentation that the concrete sits upon. One soon realizes that this is a six-foot-deep pit, exposing layers of the primordial earth below. The concrete line is paler in color and functions as a warning to the living of the presence of death nearby.

“Universal Declaration of Human Rights” recreated in soil, ash, steel, bullet-resistant glass, and burial plot

4 × 8 × 6 ft. Photo by Adam Schreiber. Courtesy of the artist.

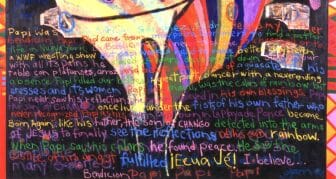

The existence of a burial plot within the confines of a gallery space is unsettling. It operates from a semiotics of death. Death is in the room with us. It is in the ethers and it is in the ground. Engaging with a conceptual expression of death enables a way back into the self. It is a rehearsal for future mourning, anticipatory grieving. The inevitable. An unmooring. A new beginning. Within many cultural imaginaries, the burial site is an observance that connotes the dead will have lived a good life, a life worthy of honoring. A burial plot is typically a specific, identifiable site within a cemetery, designated to serve as the final resting place for casketed or cremated human remains. But in its phrasing, “burial plot” offers a doubling where narrative-making is concerned. It is discernible in Los Angeles–based artist Adriana Corral’s hands and vision; in her work the burial plot serves as an inquiry into language to explore a narrative exhumed from the materiality of grief.

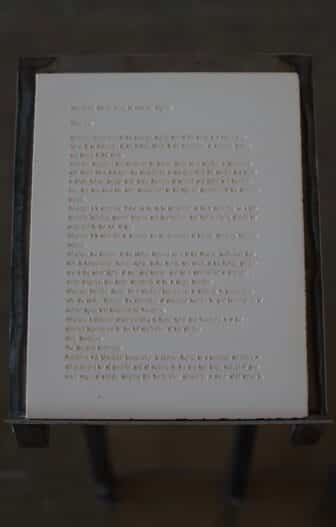

Sous Rature, “Under Erasure,” places the burial plot in conversation with eight pages of the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) that Corral has cast as eight 8 1/2-by-11-inch tablets made of soil and ash. In this configuration—first presented by ArtPace in San Antonio in 2018—and alongside the burial plot, the pages of the UDHR are made strange, turned into objects whose own semiotics of jurisprudence bend and spiral in biblical and governmental registers—a twentieth-century declaration on stonelike tablets, an incantation etched into monument form. An international document drafted and adopted by the United Nations General Assembly as a response to the atrocities committed during World War II, it speaks to the sacred specificity of the rights and freedoms of all human beings. It also speaks as a historical marker for us to remember those who were forced to live poorly by fascist governments. Sous Rature, “Under Erasure” is a hermeneutic maneuver hinging on Martin Heidegger’s tactic of crossing out a word within a text yet allowing it to remain legible and in place as if to remind us, notwithstanding our hesitance to remember, how people in proximity to atrocity are forced to normalize in order to live under the constant strain of social death. Several generations later, literary philosopher Jacques Derrida employed the notion of Heidegger’s erasure in his inquiry into writing and concomitant considerations of meaning and its inadequacies. The UDHR fails to hold governing bodies around the world accountable for the systemic violations of human rights they enact on their respective citizenry. What good is a milestone document that is globally agreed upon if it cannot effectuate for a populace under duress?

2016, site-specific installation

“Universal Declaration of Human Rights”

recreated in soil, ash, steel, bullet-resistant glass

and burial plot

4 × 8 × 6 ft. Photo by Adam Schreiber. Courtesy of the artist.

Corral’s visual coupling of the burial plot and the eight stonelike pages represents a relational tension between “everyone” and the state as we vie for a set of intimate conditions where the human being can seek and enjoy the freedoms and rights described in the UDHR’s thirty articles—including movement, mobility, family rearing, marriage, property ownership, and reputation, among others. The UDHR forged a set of intimate conditions that helped Corral animate an ethics of care she had witnessed firsthand in Geneva in 2015. She had been invited by a human-rights lawyer and former collaborator to observe testimonies of victims of government violence and disappeared family members. For Corral, the languages spoken among those collectively strategizing to pressure their governments was inspiring and spurred her to respond to this witnessing with Sous Rature, “Under Erasure.” This experience also ignited her earliest memory of an ethics of care. In an interview with the artist, Corral recalled that around the age of eight or nine in El Paso, she was allowed in the operating room by medical professionals in her family who ran a private practice. There she was permitted to stand at the head of the operating table, just above the consenting patient, to watch her cardiovascular thoracic surgeon uncle, her anesthesiologist aunt, her mother overseeing the auto-transfusion, and a close family friend who was the scrub nurse extend the life of the ailing person before them.

In Corral’s work, the eight tablets that contain the UDHR are placed across the gallery space, opposite a leaning pane of bullet-resistant glass. A viewer sees the UDHR reflected in the surface of the glass. A provocative demonstration of this work might ask viewers to imagine a scenario in which a projectile would strike the bullet-resistant glass. The purpose of ballistic resistance is to absorb the shock of the projectile and prevent it from piercing the barrier. What might it take to create a similar barrier for those whose humanity is persistently threatened in places like Palestine, Sudan, Honduras, and American schools, colleges and universities by gun violence and weapons of mass destruction?

For her rendition of the UDHR, Corral spent over two years of trial and error, perfecting the hardening of soil and ash, itself an act of repetition that yielded a masterwork of tactility. The repetition of Corral’s physical practice can be read in critical tandem to the ways repetition reinforces the authoritative statement and the means by which it underscores the importance of the UDHR document’s efficacy as a “speech act” rather than as a document of description or reportage.1

In the second half of the excerpt of the statement’s preamble, the speech act becomes activated by the verb proclaims:

Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge,

Now, therefore,

The General Assembly,

Proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.

In philosopher J. L. Austin’s formulation, a performative utterance culminates in the action it describes. For example, one might say, “I declare war”—in saying it, you do it. Or one might see in the present mode of land acknowledgments: “We honor and acknowledge the ancestral homelands currently stewarded by [the Tohono O’odham, the Diné, the Mescalero Apache, etc.].” Or consider, for example, in May 2024, when Rio Vista Farm in Socorro, Texas, was declared a National Historic Landmark with federally designated landmark plaques in English and Spanish.

site-specific stainless-steel flagpole and white cotton flag embroidered with a golden and a bald eagle.

Courtesy of the artist.

Before its landmark designation, the farm was the site of Corral’s Unearthed: Desenterrado (2018), a site-specific, stainless-steel flagpole that waved a white cotton flag embroidered with a bald eagle, representing the United States, and a golden eagle with a snake in his mouth, representing Mexico. The two eagles of distinct genera fight at their borders; their sustenance, fighting to extract their labor and win favor with the leaders of state.

Corral pinpoints her preoccupation with early twentieth-century histories of chemical warfare—particularly between the two world wars—as well as how in the development of fertilizers, chemicals were created that were applied to both land and people. Corral remembers that shortly after returning home from Berlin, she discussed her time at the UN with her father, who shared with her the connections between those atrocities abroad and the ones in proximity to her own family line. She illustrates this with an anecdote of her paternal grandfather, who was a foreman for cotton farm that a pathologist owned near Marfa, Texas, where some three hundred braceros worked the crops. Her grandfather died in a car accident shortly after a short promotional film had been shot featuring sweeping aerial views of a small plane dusting DDT over the farm, its braceros, and the breathtaking West Texas landscape. She could see her grandfather standing on the combine next to his employer, Dr. Turner. The seven minutes of footage had been in her aunt’s possession.

It seems likely that the Turner farm sourced its labor pool from the Rio Vista Farm. The term “processing” is used as a euphemism for the series of dehumanizing procedures that over a million laborers were subjected to between 1951 and 1964, including being fumigated with DDT, “a white powder used to kill insects and germs that Mexican workers were believed to carry.”2 Unearthed: Desenterrado unsettles the ideas symbolized in the Texas flag, where loyalty, purity, and bravery seep into the antagonism between Mexicans and Chicanos on the Texas–Mexico border; this can often be a mordant reminder that patriotic allegiances often skew toward survival. The subsequent fervor that surviving social death inspires rarely makes for a flag worth saluting.

Endnotes

- I borrow and utilize the term “speech act” from British philosopher J. L. Austin who, in 1955, delivered the William James Lectures at Harvard that introduced his theory of the speech act and the performative utterance in what would become his best-known work, posthumously published: J. L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1975). ↩︎

- From “A Brief History of the Bracero Program,” Bracero Oral History Project, Institute of Oral History, University of Texas at El Paso, https://tinyurl.com/47zas2te. ↩︎

Raquel Gutiérrez is the author of Brown Neon: Essays (Coffee House Press, 2022) and Southwest Reconstruction (Noemi Press 2025). Gutiérrez was recently the inaugural Writer-In-Residence in the Art department at Whittier College in Southern California and an Artist in Residence at Headlands Center for the Arts.

Cite this essay: Raquel Gutiérrez, “Adriana Corral’s Sous Rature, “Under Erasure” (2016) and Unearthed: Desenterrado (2018)” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, January 15 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/adriana-corrals-sous-rature-under-erasure-2016-and-unearthed-desenterrado-2018/