Mother Water

Y los sueños, sobre todo,

los sueños

en los que vuelven, vivos,

nuestros muertos.

—Daisy Zamora1

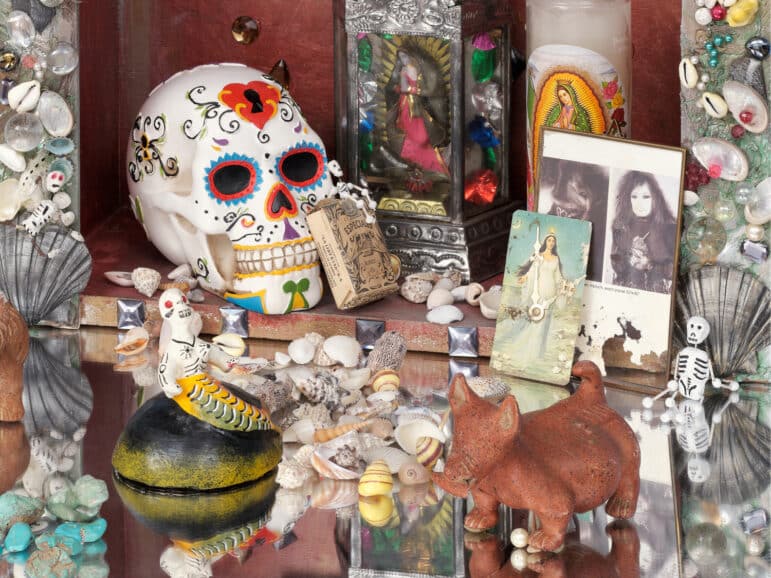

In Queen of the Waters, Mother of the Land of the Dead: Homenaje Tonantzin/Guadalupe (1993), Amalia Mesa-Bains materializes the Virgin Mary’s Indigenous and West African syncretic manifestations. Through the construction of a restive installation where the Virgin Mary is both Tonantzin, an Aztec earth deity whose Nahuatl name translates to “Our Precious Mother” and the West African water goddess and titular “Queen of Water,” Yemayá, the altar summons forth terrains, waters, and bodies devastated by colonization.2 The altar enacts a border space where the Atlantic and Caribbean oceans mix and crash against the coastlines of the Americas and West Africa, linking the memory and bodies of millions of enslaved Africans who perished during the Middle Passage with the Indigenous people who died at the hands of European settlers during their violent conquest of the Americas.

&

Water swells within and beyond the altar, pulling away

from the Bight of Biafra, crashing against Nicaragua’s

Miskito Coast. South of Cabo Gracias a Dios,

the splintered bow of the wrecked slave ship remains

among the reef in the turtle banks. The water has become

the enslaved bodies cast aboard. Their spirits rush

along the Caribbean coast, swirling cyclones, arching upstream

along the rapids of el río San Juan like the sweet water

bull shark lamenting for Cocibolca and her warm embrace—

Yemayá, are you here, too? Your altar floats in an underwater pasture

of tears, of silver coins, of cowrie shells beneath the aquamarine

curtain twisted and pinned by a master, its long wings

cascading into twin lakes. The altar is the surging horizon,

numinous grottos along the cerulean shore.

&

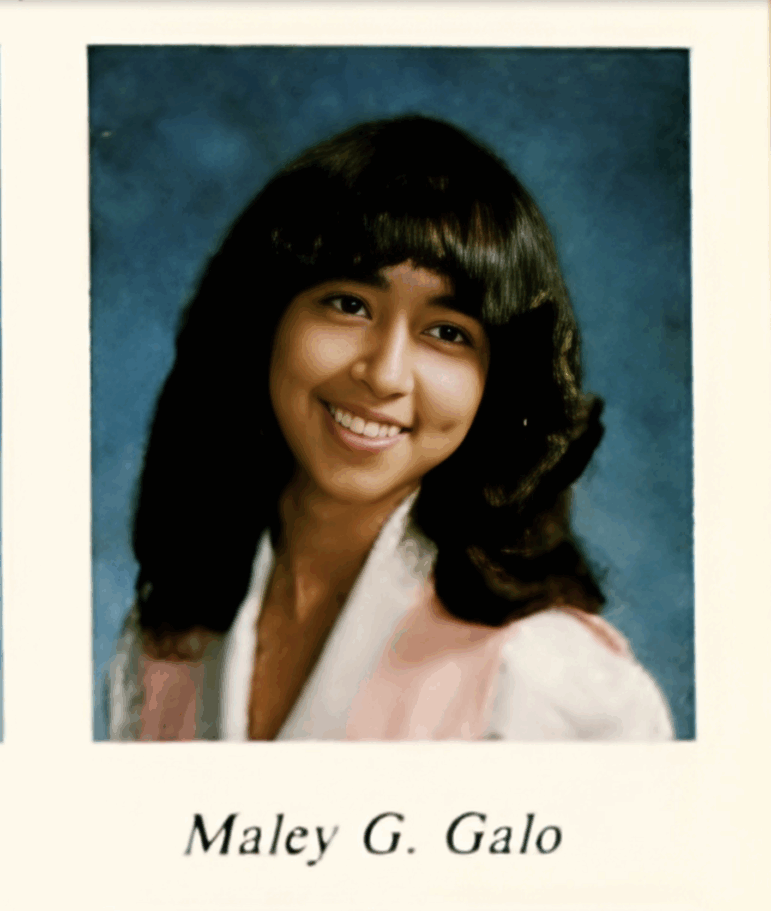

On April 27, 1981, Tía was murdered in her small studio apartment in Koreatown. She was found sitting at the foot of a loveseat in her living room.

In the autopsy report, the medical examiner describes the weight of her lungs and her heart, the dark brown color of her hair. However, they don’t tell me about the home this twenty-year-old could have built. They don’t tell me about the shape of her vanity, if it had chipped corners or if it was her prized possession. They don’t tell me if she longed for the Nicaragua she left only a few years before, for summers playing with her sisters in the brackish sweet water of Cocibolca.

The detective writes she was found “dressed for the street” with jewelry still on her hands, so I imagine her delicate fingers laced with sapphires, her fingernails long and painted azure and encrusted with foamy mother of pearls.

&

&

The tragedy of the Middle Passage transforms Yemayá, a traditionally riverine and freshwater orisha of the Yoruba religion from West Africa, into the “goddess of the sea.”3 As a saltwater deity, Yemayá embraces the enslaved Africans who are cast off or who rebel by refusing the economy of the transatlantic slave trade and throwing themselves overboard as offerings to this elemental and feminine force.4 Yemayá, the mother of humanity, fertility, and women, is summoned in through the use of blue fabric drapery that luxuriously frames the altar and recreates a river, waterfall, and oceanic horizon. Gilded vulvic oyster, conch, scallop, and cowrie shells are bountiful and embedded throughout the seventeen grottos from which la Virgen de Guadalupe emerges as she appeared to the Indigenous peasant Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin on the Hill of Tepayac in Central Mexico. This hill “a space already sacralized to the Aztec earth goddesses, generally referred to under the title of Tonantzin.”5

Mesa-Bains’s use of shells suggests that la Virgen de Guadalupe can also be born from this aquatic mandorla or vesica pisces, the vessel of the fish.6 Yemayá, who is often depicted as a mermaid or half-woman and half-fish, is then engaged in a reciprocal relationship with Tonantzin, where she gives birth to Tonantzin’s Marian devotion, which can only be worshipped through a recognition of Yemayá’s power as the goddess of the sea. If genocide transforms water into the Land of the Dead, then Yemayá and Tonantzin together transform the Land of the Dead into a source of life, fertility, and possibility for oppressed peoples.

&

My Tía comes to me in fragments from the archive. A story on the drive to the grocery store, a memory retold during a visit to her grave, but what I remember most are the vast years of silence. Pain can make memory fail, make the siren howl alone in the abyss of the wounded body forced to carry on. I wonder if my mother doesn’t talk about her because she wants the grief to end with her, wants the howl to stay below the surface of the crashing waves.

&

I’m at the heart of the maelstrom eating water,

wind, and light. I stand on the Virgins’ shoulders,

the dried pomegranates and potpourri—their divine

scent—beckons me into the frame. Mother of the Land

of the Dead, I celebrate you and count the virgins

until Cocibolca spills over. The dead and those still

waiting to be found spill into the marsh, bridging

hillside with ocean. Tonantzin, I don’t see where you end

and where Yemayá begins. I see the countless virgins

braiding together streams of time that switchback

through you both. I count the Virgins until I find which

brings back Tía, until there are no more questions,

until her body ceases to transform the private

abyss, until she’s cast out from the river to the sea.

&

&

Yemayá’s and Tonantzin’s material entanglement in the altar position them in dialogue so that they can both be felt, sensed, and otherwise experienced through one another. This gesture troubles Eurocentric logics where colonized land, water, bodies, and ways of knowing are isolated, inert, and without memory or subjectivity. Instead, Mesa-Bains blurs the border between Yemayá and =Tonantzin to reveal water as a powerful witness of colonial violence and the very land of the dead that continues to bear the bodies of enslaved people.

&

From the findings I ascribe the death to: Undetermined (Decomposed Body)

What if the decomposition is not a sign of sisters surviving

the cruelty of immigrant womanhood in Los Angeles? What if

decomposition is not the end of life, or even afterlife—but continued life?

Her body continues to transform, resists finality, shifting beyond

her consciousness, beyond matter, tries to return to the grotto,

to the lakes, to the waters of Nicaragua. What if it’s just that: a returning.

&

My mother and Tía are less than two years apart. They share

a bed each night in Los Angeles before they move or get kicked

out by their abusive father, before they take their separate paths

into that brutal city. Their pillows are cloth bags stuffed

with old clothing and sewn shut. Together, they hate them.

At night, when everyone has fallen asleep they promise each other:

when we get big, we’re going to buy all the nicest pillows we could ever want.

&

Mesa-Bains’s linking of the two divine figures of Yemayá and Tonantzin across European, African, and American terrains and waters reveals how the Virgin’s coming and going leaves in its wake a solidarity network. Here, water becomes at once mediator of movement and symbol for fixity and resistance for Indigenous peoples against colonial oppression.7

In Afro-Cuban Santería or the religions of Nicaraguan Afro Indigenous peoples like the Sambo Miskito and the Garifuna, Yemayá and her feminine water deity counterparts are respected and celebrated despite the harsh coastal environments they protect.8 Within rainforests, marshes and the Caribbean Coastal plain of Nicaragua, where the dry season is incredibly short and wet, the boundary between land and water is porous.9 Despite these porous, watery environments, Yemayá represents a restive vitality where possibility takes root, is born, and is sustained in spaces where the colonial notion of tierra firme is continually troubled. At the center of the altar lie gilded fruit, miraculously grown atop mirrored surfaces that reflect and extend the aquamarine light caught from the drapes sweeping across the installation. These fruit, alongside the calaveras whose bleached bones are radiant in their color and designs, further insist on eternal bounty from the inhospitable salt waters of the sea. The movement and transformation of these Marian devotions then also trace a transcultural genealogy of feminine defiance among oppressed women surviving the colonial legacies of machismo and violence.

&

My Tía marries her husband on January 17, 1981, and is found murdered 100 days later, 3,086 miles from her childhood home in Managua.

Addendum: A pillow suffocation cannot be excluded.

&

When I first see Tía’s signature on her wedding certificate, I notice how the blue ink reveals the sudden weight of a body. The way you can almost hear the ocean spill from the conch shell without putting it to your ear. Or how the Virgins, in their multitude, could be sisters.

Endnotes

- Daisy Zamora, “Vida con sordina,” Carátula, April 1, 2025, https://www.caratula.net/5-poemas-de-daisy-zamora/. ↩︎

- Jeanette Favrot Peterson, Visualizing Guadalupe: From Black Madonna to Queen of the Americas (University of Texas Press, 2014), 70. ↩︎

- Micaela Díaz-Sánchez et al, “Yemaya Blew That Wire Fence Down: Invoking African Spiritualities in Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza and the Mural Art of Juana Alicia,” Yemoja (SUNY Press, 2013) 153–86, 154. ↩︎

- Díaz-Sánchez, “Yemaya Blew That Wire Fence Down,” 154. ↩︎

- Peterson, Visualizing Guadalupe, 7. ↩︎

- Jennifer A. González et al, “Unruly Erotic,” Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory (University of California Press, 2023), 70. ↩︎

- Peterson, Visualizing Guadalupe, 6. Peterson writes: “Guadalupe’s translocation from the Old to the New World and back again is unique in the spiritual economy of the countless Marian devotions … This pattern of migration earned her the nickname la Virgen de ida y vuelta, literally “the virgin of coming and going”. ↩︎

- Serena Cosgrove et al, Surviving the Americas: Garifuna Persistence from Nicaragua to New York City, ed. José Idiáquez (University of Cincinnati Press, 2021), 116, 45. ↩︎

- Baron Pineda, Shipwrecked Identities: Navigating Race on Nicaragua’s Mosquito Coast (Rutgers University Press, 2006), 21. ↩︎

Reading List

Jennifer A. González, Subject to Display: Reframing Race in Contemporary Installation Art. MIT press, 2008.

Saidiya V. Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route. 1st paperback edition, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008.

Monica Huerta, Magical Habits. Duke University Press, 2021.

Stephen Kinzer, Blood of Brothers, Life and War in Nicaragua. Harvard University Press, 2007.

Maggie Nelson, Jane: A Murder. Soft Skull Press, an imprint of Counterpoint, 2005.

Kristi Osorio, “Done to Death.” New Delta Review, vol. 14, no. 1, http://ndrmagarchive.org/nonfiction/2023/12/done-to-death-by-kristi-d-osorio/

Natasha D. Trethewey, Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir. HarperCollins Publishers, 2020.

Nathan Xavier Osorio is the author of Querida (University of Pittsburgh Press), winner of the 2024 Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize. He received a PhD in Literature from UC Santa Cruz and a Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellowship from UC Irvine. He is an Assistant Professor at Texas Tech University.

Cite this essay: Nathan Xavier Osorio, “Mother Water,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, August 4, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/mother-water/