The Supernatural Queer: Mystical Ecologies and the Experience of Being Body in Felipe Baeza’s Artistic Practice

Felipe Baeza depicts the body and the world as mutually constitutive: the body takes shape within the world, and the world acquires meaning only through bodily perception. Perception becomes a dialectical relationship between the body, the world, and consciousness, where the body actively opens and closes spaces, enveloping the subject in a dynamic process of being in the world.1 Being in the world emphasizes that the body is the site of perception, action, and existence.

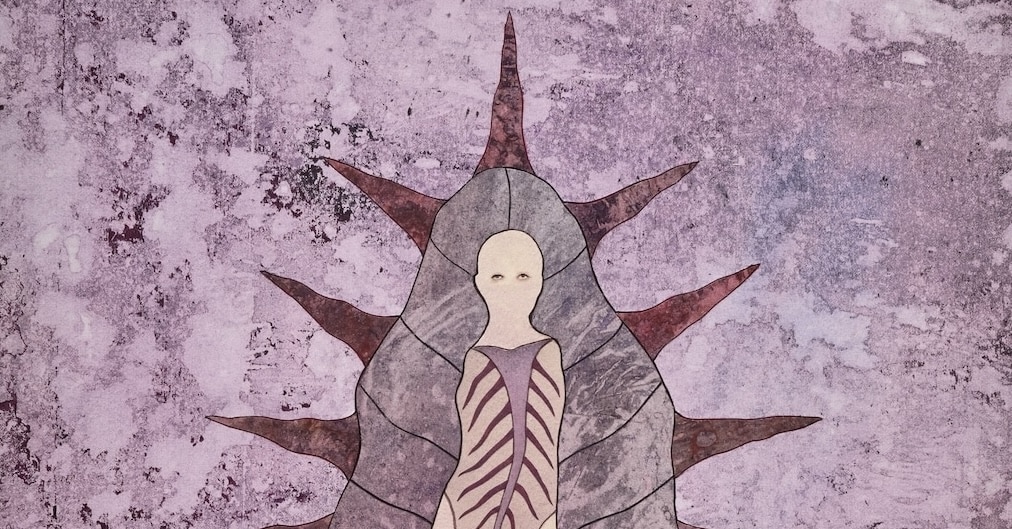

The Pounding of Steel Chopping Away at Your Flesh (2022) introduces the presence of a being with a supernatural appearance against a backdrop dominated by mottled purple tones that unfold in various forms, textures, and effects, creating an atmosphere imbued with mysticism. At the center, a body in the process of transmutation suggests a tension between interior and exterior, flesh and skin. The legs adopt a posture that, through the shape of the hips and thighs, evokes a feminine figure enveloped in a mantle or shell akin to the morphology of a mollusk or spiny organism. The folds of this organic form recall the radiant sunbeams associated with the Virgin of Guadalupe, a symbol deeply rooted in Mexican culture, as well as the form of a vagina and Christ’s side wound. This imagery draws from medieval depictions of Christ’s wound as a feminized symbol, linking the sacred and the corporeal. From the base of this organic form, two arms emerge, accentuating the corporeality of the observed figures: one resembling a human-like being, and the other a mollusk with limb-like extensions. With its arms, this supernatural being embraces and rests upon a slope, mountain, or cave, which, through a collage composition, reveals layers of earth, soil, and subsoil.

Baeza creates these images by merging printmaking, monoprint, and collagraph techniques, layering and manipulating textures on paper to produce rich, nuanced visual surfaces. Next, he affixes cutouts in the shape of bodies and other elements onto this base, arranging them to create a dynamic interplay of forms. Finally, layers of varnish further unify the surface, giving the piece the appearance of a drawing or painting. However, upon closer inspection, the collage’s layered construction reveals a distinctive technique of assembling and reassembling forms. Baeza gathers all the paper—used as a support and for the figures themselves—from a personal collection spanning multiple temporalities and provenances. This archive of papers is a catalog of textures and surfaces meticulously gathered and classified. The approach aligns with art historian Kobena Mercer’s notion of collage as a transcultural formation: a method that blends diverse visual traditions while juxtaposing and reconciling differences.2 Embracing hybridity as a central aesthetic principle, Baeza treats the picture plane as a space where human and nonhuman bodies merge, creating compositions that suggest fragmentation, transmutation, and visual cohesion. His cut-and-mix collage aesthetic exemplifies the condition of Nepantla—a Nahuatl concept that describes a state of in-betweenness, hybridity, and cultural liminality.3 This aesthetic opens a dialogue on the historical interactions and interconnectedness of Latinx cultures and ancestral legacies across the United States, Latin America, mestizo cultures, and their ancestral legacies.

The juxtaposition and recombination of various materials, textures, visual references, temporalities, and forms within this slope construct a space that not only supports the body in transition but also alludes to a multidimensional transformation—not just in the figure’s organs, skin, skeleton, and the mantle that envelops it, but also in its location amid different spaces and surfaces. This transmutation suggests a continuous transit between worlds, terrains, and subterranean realms. Mountains and caves were symbolically and practically important in Mesoamerican civilizations, representing the cosmic axis (axis mundi) linking the heavens, earth, and underworld, while also revered as “containers of water” that sustained agriculture and life through rivers, springs, and aquifers.4 The interplay of materiality and symbolism emphasizes the figure’s passage through transformative spaces, where the boundaries between the physical, spiritual, and cosmic realms blur, invoking a continuity between the earthly and the divine.

For the figures, Baeza draws inspiration from Mesoamerican art, where fused forms between humans and animals were frequently depicted and often linked to shamanic practices.5 These metamorphoses symbolized access to spiritual realms or the merging of human and animal powers. Ancient American ceramic forms and carvings usually feature figures that combine traits of various animals (such as jaguars, birds, and snakes) with human characteristics. These hybrids are associated with rain and agriculture, embodying deities, ancestors, or spiritual guides.6 Within the Mesoamerican worldview, these figures were essential for ensuring the fertility of the land and maintaining the ecological balance.

Baeza envisions spirituality as a transformative force deeply tied to queer and Latinx experiences. His work challenges normative views of nature and the supernatural, emphasizing fluid, entangled relationships among human, nonhuman, and spiritual beings. This exploration of fluidity aligns with Gloria Anzaldúa’s notion of entering into the serpent, which sees the body as an extension of the natural world and underpins her concept of mestiza consciousness—a challenge to rigid binaries that embraces hybridity as survival and resistance. It also informs her theory of conocimiento, where identity is not fixed but exists as “a composition of a composite,” a shifting assemblage of selves within “a field of subpersonalities.”7 Baeza visually embodies these overlapping (id)entities through the metamorphosis of his figures, where transformation blurs the boundaries between human and supernatural animal forms. For him, the supernatural is both a metaphor and a site of liberation, offering queer identities a space for fluidity and resistance. Drawing from Indigenous, Afro-diasporic, and Catholic practices, Baeza explores spirituality as an act of defiance against colonial and heteronormative structures.

The supernatural being, covered in spines, evokes a relational superficiality: its surface can inflict pain but also functions as a protection mechanism. The mantle that envelops it appears as an additional surface, a second skin that parallels the slope, mountain, or hill upon which it rests. This highland reveals its internal layers, divided by a section reminiscent of a set of teeth, complete with incisors and fangs, suggesting an orifice, a mouth, or an access point to the interior of a cave. This element, combined with the thorns of the shell, creates a conceptual tension between the act of touching, the potential for wounding, and the exploration of interiority—whether it be the flesh or the subsoil. As Merleau-Ponty notes, “Surface and depth are not opposites; the surface opens onto depth,” which suggests, furthermore, that surface and depth are interwoven dimensions of experience.8 In Baeza’s work, the body in transition is perceived in a state of displacement across different worlds, manifesting as diverse entities: something seemingly human yet also adopting animalistic, monstrous, and metaphysical forms. This series of works encapsulates the mystery and secrecy of the world, embodying a spirituality that unfolds through corporeality, mutation, and deformity.

The artwork presents a body that perceives and interacts with the world through its epidermis, dermis, cartilage, musculature, and viscera, engaging in a continuous process of adaptation and transformation. In this ongoing flow, the boundaries between interior and exterior dissolve, revealing a porous and fluid relationship with its surroundings. Rather than being a static object within the world, the body emerges as an active participant in shaping and redefining spatial and sensory experiences.

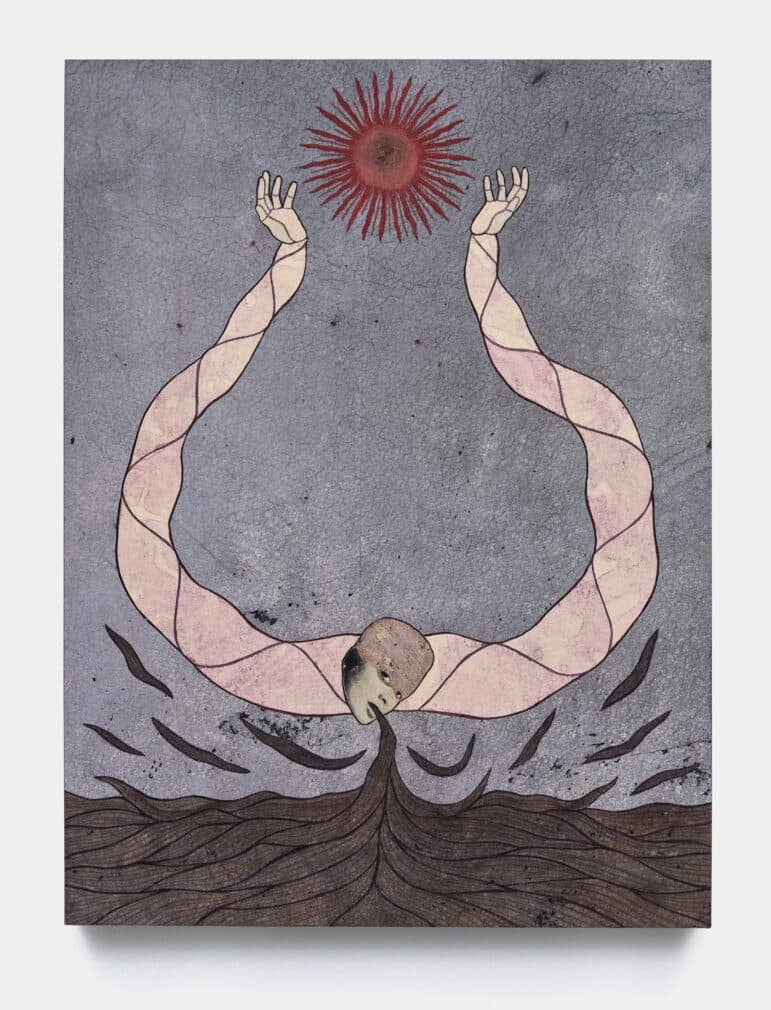

The Fragile Sky Has Terrified You Your Whole Life (2022) brings forth another supernatural being, depicted as an elongated, serpentine figure composed only of arms and a face positioned at their center. With no torso, one arm—undergoing metamorphosis—intertwines with the other, twisting like a living snake to form an ever-shifting structure of arms and forearms. The hands, simultaneously budding and decaying, mark both the beginning and end of the body. From its mouth, the being exhales a substance resembling vines or leaves in shades of brown and dark green, evoking earthy tones like those of fertile soil or forest undergrowth. The substance extends and covers the painting’s lower register, while the textured grayish-blue background above contains a bright orange sun emitting over forty wavy red rays. The sun hovers between the being’s hands, which seem to reach out to catch or contain it. This gesture, along with the exhalation of organic matter, evokes a transformative cycle akin to photosynthesis, where solar energy catalyzes the creation of life and growth—symbolically mirrored by the absorption of sunlight, which transforms the being’s exhaled substance into earth or vines, creating a space for planting and regeneration.

The leafy green-brown substance exhaled by the being suggests the emergence of a queer futurity—a space yet to come that reimagines existence. In line with José Esteban Muñoz’s concept, this transformative vision embodies a utopian potential where queer experiences disrupt normative structures, fostering growth, renewal, and new worlds.9 These new worlds hold particular significance for artists in the diaspora, as the materiality of collage—through its assemblages and layers—reflects the fragmented and recombinatory nature of diasporic identities. By exhaling vines or earth, this substance transforms the painting’s foreground, reconfiguring the landscape into a body of water or an unstable surface. This act implies regeneration and the potential to sow in unfamiliar territories, imagining and inhabiting new spaces. The movement between surfaces is not merely a geographic transition but a transformative act, where bodies in motion intervene in the territories they encounter, producing new cycles of life. This gesture resonates with themes of resistance and the reimagining of borders, proposing fluid and open forms of belonging that challenge the normative structures regulating spaces and their inhabitants.

By challenging traditional notions of form, function, and hierarchy that typically structure representations of bodies and natural cycles, Baeza aligns his work with queer ecologies. The serpentine, fluid, and metamorphic figure disrupts binary conventions of corporeality. As a being that extends beyond human and animal boundaries, it suggests an organic interconnection between terrestrial and celestial elements. Through inhaling and exhaling energy in the form of earth and vines, the creature articulates a cycle of transformation that resists linear categories of production and consumption, proposing instead a more integrated and regenerative relationship with its environment. This gesture of reciprocity and transmutation challenges normative structures of interaction between bodies, nature, and energy, imagining supernatural and non-heteronormative alternatives for coexistence.

Felipe Baeza’s work occupies the intersection of the supernatural and queer ecologies, challenging the binary categories that have historically shaped notions of body, space, and spirituality. By depicting supernatural beings that traverse the realms of the human, the animal, and the monstrous, inhabiting territories between the earthly and celestial, Baeza proposes a continuity between corporeality and landscape that resists the hierarchies imposed by normative systems. His work engages with unmasking coloniality, revealing the persistent power dynamics shaping identities and systems of knowledge in the Americas.10 Through elements such as metamorphosis, the exhalation of earth, and hybrid beings, Baeza rejects traditional religious dogma, visualizing a symbiotic interaction between bodies and environments. While his works suggest the possibility of future belonging, they center on self-transformation—an inward, esoteric process that precedes communal solidarity. In Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro, Anzaldúa describes tono as a force that animates the being through dreams, visions, and introspection, guiding transformation.11 Thus, Baeza’s work does not depict an achieved collectivity but visualizes the metamorphic passage that could lead toward one. His art expands the boundaries of queer ecologies, proposing modes of existence that embrace fluidity, transformation, and an emerging relationship with both the material and immaterial, the human and the nonhuman.

Endnotes

- See Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962), 146. ↩︎

- See Kobena Mercer, “Kerry James Marshall: The Painter of Afro-Modern Life,” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, no. 24 (2010): 86. ↩︎

- See Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza, critical edition, ed. Ricardo F. Vivancos Pérez, Norma E. Cantú, and AnaLouise Keating (Aunt Lute Books, 2021). ↩︎

- See Brigitte Faugère and Christopher S. Beekman, eds., Anthropomorphic Imagery in the Mesoamerican Highlands: Gods, Ancestors, and Human Beings (University Press of Colorado, 2020). ↩︎

- Karl A. Taube, Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2004). ↩︎

- Taube, Olmec Art. ↩︎

- Anzaldúa, Borderlands. ↩︎

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, ed. Claude Lefort, trans. Colin Smith (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962), 146. ↩︎

- See José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York University Press, 2009). Muñoz explores the concept of queer futurity as a radical vision that reimagines alternative ways of existing, disrupting normative structures and creating transformative spaces of possibility and growth. His work offers a framework for understanding queer identities and experiences as sources of potential, capable of generating a utopian, yet-to-come space. ↩︎

- Aníbal Quijano, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America,” Nepantla: Views from South 1, no. 3 (2000): 533-580; Walter D. Mignolo, The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options (Duke University Press, 2011); Maria Lugones, “Heterosexualism and the Colonial/Modern Gender System,” Hypatia 22, no. 1 (2007): 186-219. ↩︎

- Gloria Anzaldúa, Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality, ed. AnaLouise Keating (Duke University Press, 2015). ↩︎

Eduardo Carrera R. is a curator, art historian, and cultural manager. A PhD candidate at the University of Pennsylvania, his research focuses on Latin American, Latinx, and queer art. He was Curator and Coordinator of CAC Quito (2017–2022) and has collaborated with institutions such as Wrightwood 659, Independent Curators International, MoMA, Visual AIDS, Penn Museum, MACBA Barcelona, and PIVO São Paulo, among others.

Cite this essay: Eduardo Carrera R., “The Supernatural Queer: Mystical Ecologies and the Experience of Being Body in Felipe Baeza’s Artistic Practice,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, August 4, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/the-supernatural-queer-mystical-ecologies-and-the-experience-of-being-body-in-felipe-baezas-artistic-practice/.