Postcommodity and the Latinx-Indigenous Continuum: Epistemic Resistance through Material, Form, and Sound

Postcommodity’s interdisciplinary art practice challenges and redefines the intersections of Latinidad, Indigenous knowledge, and contemporary art. Postcommodity is a collective that is currently composed of artists Cristóbal Martínez, of Genízaro, Manito, Chicano, and Xicano ancestry; and Kade L. Twist, an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation. Together, they imbue epistemic resistance and drive materials and art installations into interventions that question institutional power structures, labor, and historical narratives. This essay analyzes two works: With Each Incentive and From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home, to explore how Postcommodity’s practice uses collective memory to decolonize bodies and spaces. The collective deploys a methodology for decolonizing sites and spaces shaped by extractivism and colonial supremacy through industrial materials, Indigenous aesthetics, participatory engagement, and sound. Situating their work within the lineage of Latin American Constructivism and Concretism illuminates how Postcommodity reimagines contemporary art and institutional spaces through Indigenous and Latinx perspectives.

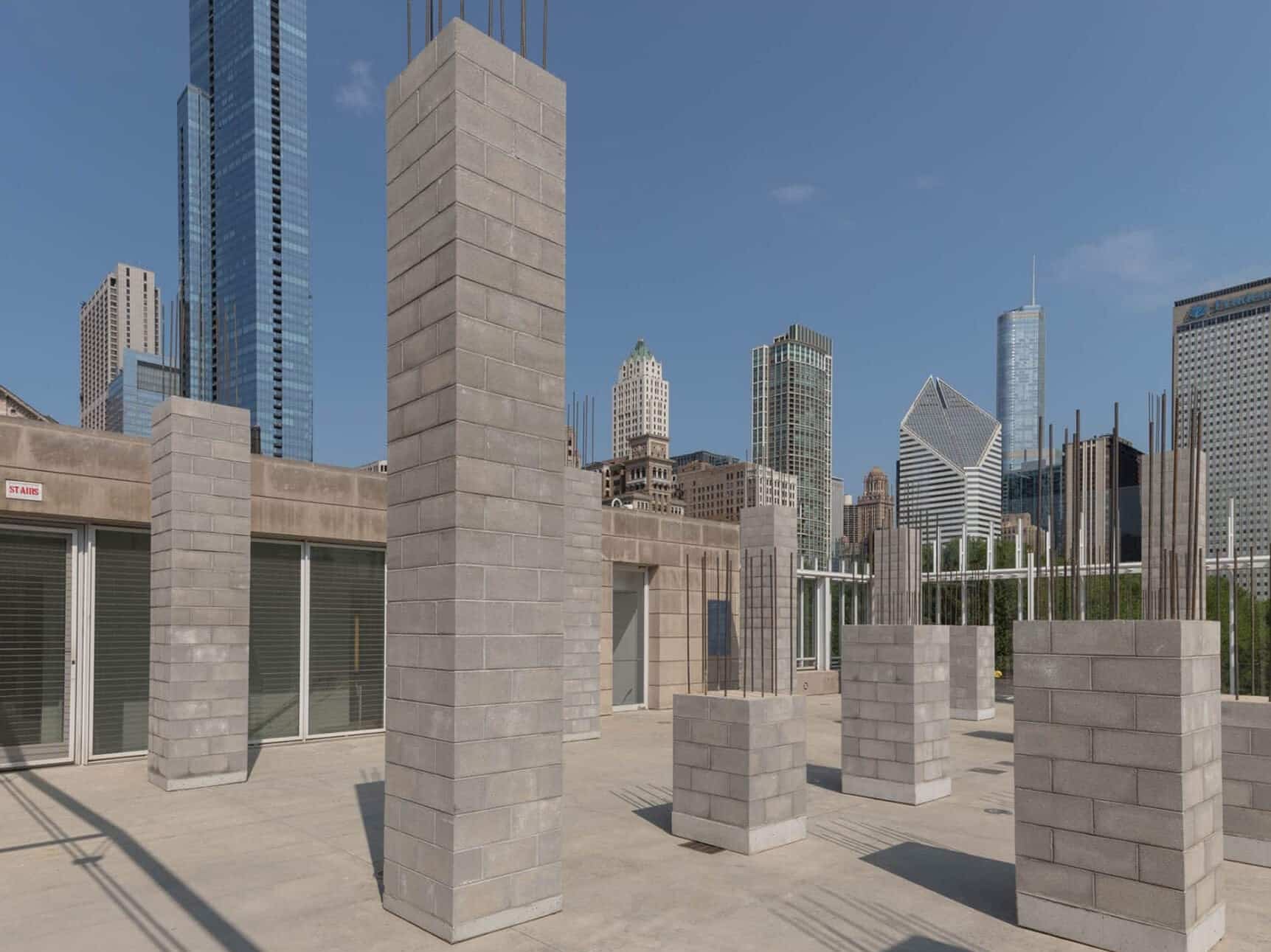

In 2019, Postcommodity exhibited With Each Incentive at the Bluhm Family Terrace, a publicly visible yet privately rentable space in the Art Institute of Chicago. The installation comprised eighteen columns made of cinder block and rebar, known as castillos through Latin America. These frameworks, which traditionally serve as anchors within buildings, ranged from one to five meters in height. The sheer weight of the sculpture prompted the museum staff, board members, and stakeholders to discuss the provocation of such a visually imposing artwork within the museum’s rental space and the impact on the building’s structural integrity.

Across Latin America, builders leave exposed rebars protruding upward from the tops of castillos, appearing like articulated fingers reaching for the sky. Their purpose is pragmatic: leaving a connection point to expand a home as a family grows or can afford additional living space, while leveraging a tax loophole that reduces property taxes. With Each Incentive speaks to Latin Americans’ socioeconomic realities and an Indigenous American worldview of continual emergence, “always becoming,” a philosophy that echoes Paulo Freire’s assertion that humans are beings in the process of becoming, unfinished and uncompleted, shaped in relation to a likewise unfinished world. Both frameworks resist static identity instead embracing transformation as a condition for liberation, healing, and collective learning.1

With Each Incentive was built by a local construction company that employed Latinx workers, bringing them into the museum to carry out the labor. Through building the form, the workers, familiar with castillos and their function, contextualized pedagogical frameworks that decolonize artistic production through a subversive methodology. As they built the sculpture, the workers took on the role of what Pablo Helguera calls a “nonvoluntary participant.”2 Postcommodity’s impetus for the artwork reflects the oppressive conditions surrounding Latinx labor. Whether by design or through circumstance, the collective confronted the exploitative dynamics of the labor and art production, ultimately cultivating an exchange of knowledge and stories about castillos, a process that fostered a pedagogical discourse rooted in respect, reciprocity, and relationality. These gestures of inclusion, solidarity, and dignity demonstrate Postcommodity’s decolonial methodology that rejects Western art’s emphasis on individual genius in favor of collective memory, love, and shared experience.

In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire reminds us that labor is a form of meaning-making, not just production. He reminds us that love is not sentimental; but political and a commitment to liberation. Love is to recognize people’s dignity and capacity as subjects of history, capable of naming and transforming the world. In other words, they are active participants in shaping their reality rather than objects of oppression.3 Like Freire, Postcommodity urges us to rethink participation and agency, asserting that when labor is defined by dependence, insecurity, and ongoing threat, it strips individuals of fulfillment. With Each Incentive confronts this condition by dignifying the workers as cocreators rather than passive laborers.

Postcommodity echoes Freire’s vision of liberation by recognizing dialogue and labor as central to human dignity. It treats words as a form of praxis—where reflection and action are inseparable—and affirm that owning one’s labor is essential to being fully human. By centering the workers’ voices through storytelling and art production, the collective honors dialogue and asserts that humanity is reclaimed, not granted, through the radical clarity of critical consciousness.4 The architecture of power builds and upholds boundaries that elevate a privileged few while systematically denying entire communities the recognition, resources, and the voice they intrinsically deserve. Historically, powerful institutions have actively reinforced these divisions that marginalize and oppress others. Meaningful change requires the oppressed, together with allies in true solidarity, to engage in dialogue, collective struggle, and deepen their understanding of the systems that constrain them. 5 With Each Incentive emerges from this awareness, challenging institutional authority and broader structures of power, labor, authorship, and cultural agency. Rather than existing solely as an object for observation, it is a living pedagogical act transforming the world through decolonial praxis.

Another premier institution, the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, commissioned From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home in 2018. This site-specific installation was presented at the 57th Carnegie International and installed in the museum’s Grand Hall of Sculpture. Raven Chacon, a Diné and Chicano composer, performer, and visual artist, was a member of Postcommodity from 2009-2018 and From Smoke and Tangled Waters represents his final collaboration as part of the collective. Described on the artists’ website as “a sculptural graphic score of coal, glass, and steel for solo jazz performance,” the work was monumental in scale, stretching over an expanse of 3,200 square feet of floor space.6 From the Hall’s balcony, viewers encountered a striking abstract composition—an Indigenous aesthetic through assembled materials referencing the North Star skyscape–producing angular patterns and a shifting kaleidoscope of light and shadow. The work drew from the city’s earlier twentieth-century identity as an industrial powerhouse and recalled the legacy of the museum’s founder, Andrew Carnegie. From Smoke and Tangled Waters also functioned as a sonic intervention within the space, as Chacon collaborated with local musicians to rehearse co-intentional interpretations of the graphic score, which were performed throughout the exhibition.7

Postcommodity, who often includes sound as a key element of their projects, designed From Smoke and Tangled Waters as a dialogue between visual abstraction and performative artmaking. Every week while the installation was on view, musicians from the local Afro American Music Institute and Chicago’s jazz community performed the graphic score. A graphical score uses visual symbols, illustrations, or abstract designs to communicate how a piece of music should be performed or interpreted. The musicians animated the installation with a dynamic interplay of sound, drawing from Indigenous and Euro-American instruments. They moved between the deep resonance of conch horns and the metallic flare of trumpets and trombones. Their music echoed through the Grand Hall, colliding with the cold marble of neoclassical nude male statues amassed by Andrew Carnegie. These echoes unsettled the space, fracturing the colonial grandeur sonically, ideologically, and symbolically. They manifested what José Medina calls “epistemic friction,” the moment when marginalized voices challenge dominant spaces, reshaping how history and knowledge are perceived. 8

From Smoke and Tangled Waters draws from African American and Indigenous traditions that honor shared experiences and common realities, challenging Western conventions of individual capital and singular narratives. In contrast, Postcommodity engaged with layered and interconnected histories. Medina claims that resistance gains strength through pluralisms and interconnected actions rather than isolated efforts, aligning with Postcommodity’s emphasis on collective meaning-making. Their work disrupts historical silences through sound and materiality, activating counter-memory to reclaim narratives erased by dominant histories.9

Postcommodity challenges the dominant narrative of Latin American modernism, revealing its foundations not as European imports but as continuations of Indigenous knowledge and practice. Their work recalls the philosophy of Joaquín Torres-García’s Constructive Universalism, particularly in its emphasis on Indigenous art production, collective authorship, economic structures, and relational aesthetics; and grounded in the constructivist belief that meaning is actively constructed rather than passively received.

In the 1930s, the Uruguayan Joaquín Torres-García (1874-1949) proposed Constructive Universalism, a form of geometric abstraction framed as an intrinsic part of Indigenous tradition rather than an imported European aesthetic. He maintained that Latin American artists were not copying foreign models but continuing ancient traditions of pre-Columbian art based on rational geometry principles, what curator Mari Carmen Ramírez calls “Indigenous constructivism.”10 This attribute is visible in Postcommodity’s From Smoke and Tangled Waters, where shards of glass, concrete, coal, and steel assembled into abstract geometric forms resemble Concretist principles, continuing ancient traditions. Torres-García argued that geometric abstraction invents its own form of unity by relating the individual parts of the composition to the overall whole.11 Postcommodity engages with materiality as a site of historical continuity and contemporary resistance, demonstrating that Indigenous abstraction is not only a historical artifact but a living, evolving practice.

Postcommodity also shares Torres-García’s commitment to reframing institutions as sites of resistance rather than passive preservation. Torres-García challenged the idea of art institutions as static repositories of culture, instead advocating for “new ideology.” As outlined in The Arcadian Modern, Torres-García rejected the elitism of European modernism, stating that art should function as a universal language accessible to all rather than reserved for the privileged.12 Postcommodity carries this vision forward by intervening in institutional spaces, disrupting colonial narratives, and centering Indigenous perspectives within contemporary museum settings. Much like Torres-García’s Escuela del Sur, a school and eventually a movement, which sought to redefine Latin American art in opposition to European dominance, Postcommodity aims to transform institutions into arenas of decolonial discourse, where power structures are interrogated and redefined.

Postcommodity’s work reveals the transformative power of collective artmaking as a decolonial force that reimagines both art and the institutions that frame it. Their practice centers Indigenous and Latinx knowledge systems as vital to reshaping how we understand labor, memory, and authorship. With Each Incentive honors the often-erased labor of Latinx workers, while From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home reverberates with ancestral presence and history of place through sound and material. Reflecting Latin American Constructivism and Concretism, their practice moves between continuity and rupture, offering art as a living, political act. In their hands, the institution becomes a site of disruption, resistance, and radical cultural affirmation.

- Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc., 2005), 84. ↩︎

- Pablo Helguera, Education for Socially Engaged Art (Jorge Pinto Books, 2011), 14-17. ↩︎

- Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 51-52, 88-90, 101. ↩︎

- Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 90-92, 183. ↩︎

- Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 51, 77, 85, 92, 163. ↩︎

- “From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home,” Postcommodity, accessed March 22, 2025, https://postcommodity.com/FromSmokeAndTangledWaters.html. ↩︎

- Julie Hannon, “Reconstructing History,” Carnegie Museums, accessed November 17, 2025, https://carnegiemuseums.org/carnegie-magazine/fall-2018/carnegie-magazine-reconstructiong-history/. ↩︎

- José Medina, The Epistemology of Resistance (Oxford University Press, 2013), 233-234, 257, 283-284. ↩︎

- Medina, The Epistemology, 222-229, 281, 289, 295. ↩︎

- Alexander Alberro, “To Find, To Create, To Reveal: Torres-García and the Models of Invention in Mid-1040s Río de la Plata,” in Joaquín Torres-García, The Arcadian Modern, ed. Luis Pérez-Oramas (The Museum of Modern Art, 2005), 109. ↩︎

- Alberro, “To Find,” 109-110. ↩︎

- Alberro, “To Find,” 107-108. ↩︎

Rooted in the ancestral knowledge of the Sierra Madre Occidental, Jeanette Degollado bridges contemporary art, the public sphere, and social enterprise to explore modalities of pedagogical frameworks, knowledge systems, meaning-making, and economic mobility. Degollado holds a BA in Communications and Studio Art from the University of Houston and earned her MFA from Otis College of Art and Design in 2016.

Cite this essay: Jeanette Degollado, “Postcommodity and the Latinx-Indigenous Continuum: Epistemic Resistance through Material, Form, and Sound,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, October 29, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/postcommodity-and-the-latinx-indigenous-continuum-epistemic-resistance-through-material-form-and-sound/