Our Mother Portable Mural: Yolanda M. López’s Nuestra Madre (1981-1988)

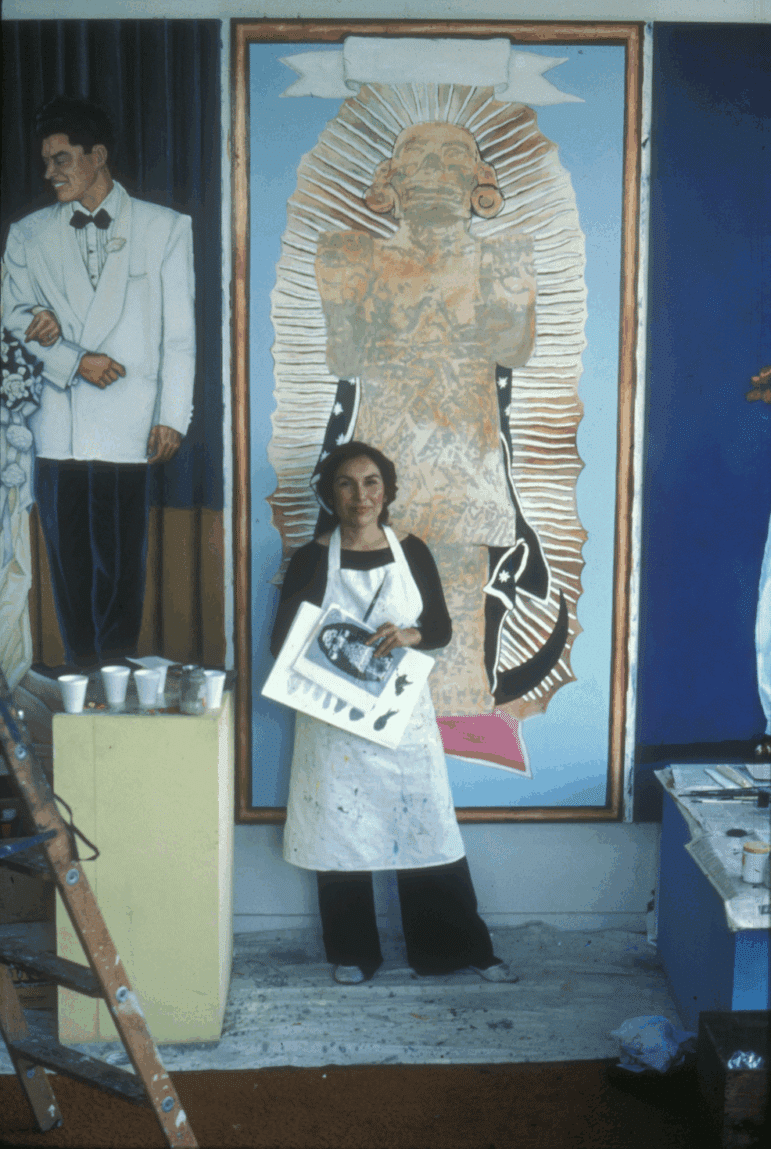

In a 1982 color photograph, Chicana artist Yolanda M. López stands confidently in front of a six-foot-tall Masonite panel for the exhibition In Process, In Progress curated by Rene Yañez.1 Her stance and slight smile conveyed a poised gesture proudly displaying her unfinished artwork. The photograph shows the artist’s primary coat of acrylic paint outlining the enlarged image of the Pre-Columbian Nahua goddess named Coatlicue as a sculptural figure with added elements that reference the Catholic Virgin Mary specifically La Virgen de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe). López’s portable mural shifted our understanding of the genre as a static medium confined to a wall by creating a transportable image that reflected a reimagining of Our Mother goddess as an emboldened figure. The movable panel, later titled Nuestra Madre, functioned as public art because it ignited emotional and intellectual conversations about spirituality, history, and culture in the Mexican American, Chicana/o, and Latina/o community.

The exhibition In Process, In Progress provided the public an opportunity to observe local artists paint large moveable Masonite panels inside the Galería de la Raza in San Francisco’s Mission District. Tim Drescher explained that the exhibition captured a unique “non-alienated artistic experience” in which the artists and the community were integral to the process of creating public art much like “U.S. community muralists.”2 René Yañez noted that the exhibition was a rare opportunity where artists were able to talk to each other “while they worked,” but also “watch each other’s techniques and ask about the properties of unfamiliar paints, new problems with perspective, general concepts of their work,” and “people dropped in on a daily basis” engaging in conversation with the artists.3 Ella Diaz explained Yañez was inspired by the Mexican muralists and the idea of bringing the “pueblo or populist principles of art making into the design of In Progress,” which was the practice of producing moveable murals “in front of an audience.”4

Yañez’s approach created a collaborative and generative environment in the gallery, however, he did not anticipate the challenges of withstanding the criticism from visitors prior to the exhibition opening. During the third week of In Process, In Progress, a member of a religious group expressed “strong opposition to the painting.” Drescher noted that López and an anonymous woman discussed the “problem at length” and once she “understood the image” thought it was beautiful but still requested “explanatory material” for some artworks. In response, artists agreed and statements about each panel were placed at the front door of the gallery opening. There was an emotional response from local audiences because of the reproduction of a religious image that viewers may have interpreted as impolite. López responded to this occurrence stating, “I am emotionally involved with it, too,” to demonstrate her respect for the religious icon.5 This encounter between the artist, the artwork, and the viewer signified a moment where the complexities of form and aesthetics resulted in conversation, not censorship.6

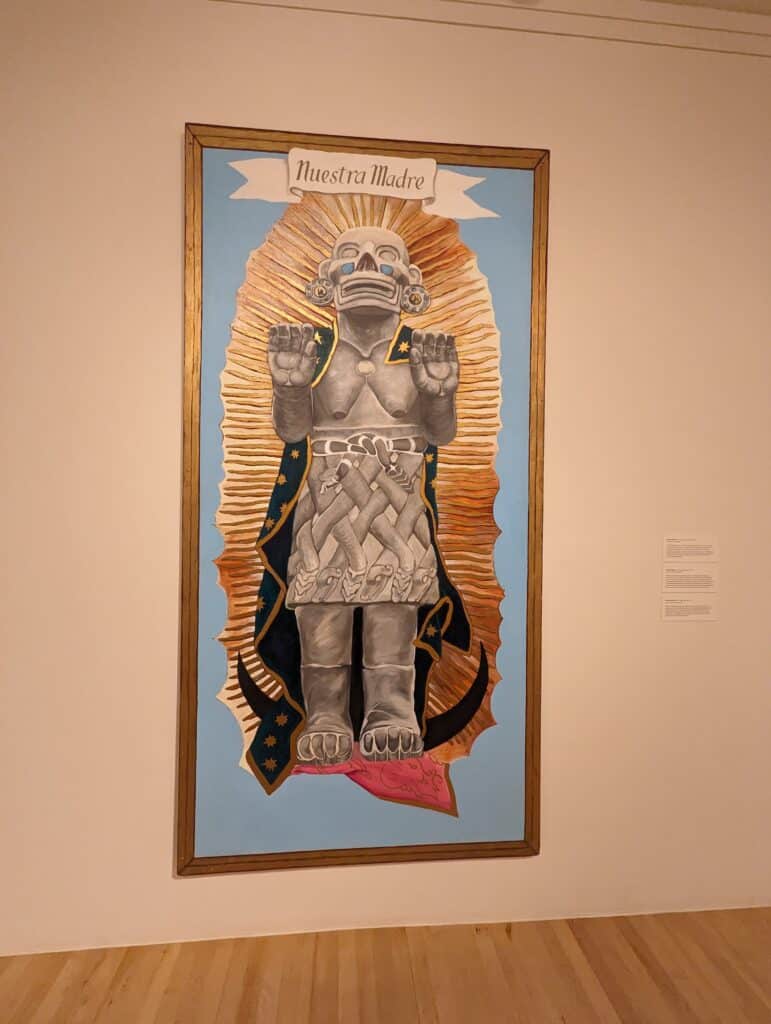

López’s representation of the Coatlicue of Coxcatlán, from the state of Puebla, México, draped in the cerulean-green cloak of La Virgen de Guadalupe visually fused the concept of the mother goddess as the subject of the mural. The Coatlicue or “Snakes-Her-Skirt” in Nahuátl is commonly recognized as the giant ten-foot-tall Aztec sculpture comprised of snakes as her head, upper, and lower body while wearing a serpent skirt. The goddess is known as the “mother of the Aztec’s patron deity Huitzilopochtli” portrayed as a dismembered or decapitated body with protruding snakes from her arms and head to signify the gushing of blood.7 The lesser known sculpture of Coatlicue of Coxcatlán, a three-foot-tall artifact from the Late Postclassic period (c. 1300-1521 C.E.), has distinct features including the goddess’s body as an anthropomorphic “bare breasted” female figure with outstretched hands. Elizabeth Hill Boone described the figure as a catlike character wearing “mittens and boots that are the paws of a feline” with circular shaped turquoise stones inserted into the palms, cheeks, and chest.8 Mexican muralist Diego Rivera resurfaced the image of the Coatlicue of Coxcatlán in the portable fresco Pan American Unity (1940), as a bio-mechanical figure with a raised forearm and turquoise stoned palm, serpent skirt, and a feline face placed in the center of the composition. Rivera and his assistants were displayed in the act of painting the portable fresco at the Golden Gate International Exposition but did not interact with the audience.9 Rivera’s portable fresco transformed the potency of the Indigenous Nahua goddess and renewed the image’s relevance to modern audiences.

López’s visual strategy differed from Rivera’s because her mural readdressed the significance of the Coatlicue of Coxcatlán as an ancestral mother goddess combined with elements of La Virgen de Guadalupe’s cloak, crescent moon, solar mandorla, and the pink dress placed underneath Coatlicue’s feet. Karen Mary Davalos explained this fusion as an “effective reconstruction of Chicana womanhood,” because it maintained a spiritual and cultural power in its “autonomous” presence — one that is not “defined” by men. Per Davalos, the image revived the historical icons but also inserted a Chicana feminist reimagining liberating them from a patriarchal dichotomy based on the virgin/whore binary while contributing to a “fuller understanding of what humanization means.”10 The design was conceptualized in 1978, titled Coatlicue and Guadalupe, where López envisioned a collage of historical images conveying the four apparitions of La Virgen de Guadalupe to the Indigenous Nahua and Marian devotee Juan Diego bordering the Coatlicue sculpture.11 This detail was removed, and the composition was modified to emphasize the sculptural grayscale quality of the object contrasting with the soft pastel blue background as well as the blue-green mantle and golden rays.

Nuestra Madre is a Chicana feminist re-vision of the mother goddess that pictured the survivance of Indigenous Mesoamerican culture.12 The presence of Coatlicue and La Virgen de Guadalupe conjured a powerful message that exalted Indigenous, Mexican, Chicana, and Latina women using her own research and admiration of the Catholic image. López’s portable mural served to harmonize the dual goddesses as icons representing empowerment and resilience but also generating contentious dialogue for generations to come.

- Tim Drescher, Progress in Process: Catalog of the Exhibition (La Raza Graphics Center, 1982). Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Tomás Ybarra-Frausto research material, 1965–2004, box 11, folder 27. The panel was untitled in 1982 but was later given the title Nuestra Madre. Each Masonite panel measured 6 × 4 feet, and López finished her panel with Liquitex acrylic and oil paint, 1981–88. The completion date was noted in the exhibition Yolanda López: Portrait of the Artist, courtesy of the Yolanda López Legacy Trust. ↩︎

- Drescher, Progress, 7. ↩︎

- René Yañez, “In Progress 1982,” announcement letter sent to Tomás Ybarra-Frausto prior to the exhibition opening, with a copy of the catalog, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Tomás Ybarra-Frausto research material, 1965–2004, box 11. ↩︎

- Ella Maria Diaz, “Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts: Recovering a Conceptual Mission Mural,” Proyecto Mission Murals, September 2022. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/greater-than-the-sum-of-its-parts-recovering-a-conceptual-mission-mural/. Diaz explains, “Rivera’s murals were certainly well known to Yañez, as well as members of MALA-F and the In Progress artists.” Rene Yañez was a founding member of a “vanguard Chicano art collective” called the Mexican American Liberation Art Front (MALA-F). ↩︎

- Drescher, Progress, 16. ↩︎

- This moment precedes the censorship of Alma López’s digital collage print titled Our Lady, finished in 1999, while on display in the 2001 exhibition Cyber Arte: Tradition Meets Technology at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico. See Our Lady of Controversy: Alma López’s Irreverent Apparition, eds. Alma López and Alicia Gaspar de Alba (University of Texas Press, 2011). ↩︎

- Cecelia F. Klein, “A New Interpretation of the Aztec Statue Called Coatlicue, ‘Snakes-Her-Skirt,’” Ethnohistory 55, no. 2 (Spring 2008), 229, https://doi.org/10.1215/00141801-2007-062. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Hill Boone, “The ‘Coatlicues’ at the Templo Mayor,” Ancient Mesoamerica 10, no. 2 (1999): 196-197, fig. 15, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536199102098. ↩︎

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) information on Rivera’s mural Pan American Unity (1940), https://www.sfmoma.org/exhibition/pan-american-unity/. ↩︎

- Karen Mary Davalos, “Guadalupe as Feminist Proposal,” in Yolanda M. López. A Ver: Revisioning Art History, Volume 2 (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2008), 96-97. ↩︎

- Yolanda M. López, interview with Cherríe Moraga and Celia Herrera-Rodríguez, Las Maestras Center, UC Santa Barbara, February 12, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wZ0SJn1OCFU; Yolanda M. López, Coatlicue and Guadalupe (1978), Xerox on found print, 6 ½ × 8 ½ inches. See Davalos’s Yolanda M. López, 98, figure 56. ↩︎

- See Gerald Vizenor, Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence (University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 1. The term is explained by Vizenor: “Native survivance is an active sense of presence over absence, deracination, and oblivion; survivance is the continuance of stories, not a mere reaction, however pertinent. Survivance is greater than the right of a survivable name.” ↩︎

Dr. Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez‘s research contributes to the social art history of Chicana/o/x and Latina/o/x art and murals in the U.S. and México. Her interdisciplinary approach includes methodological practices and theoretical frameworks in art history and Chicana/o/x and Central American studies.

Cite this essay: Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez, “Our Mother Portable Mural: Yolanda M. López’s Nuestra Madre (1981-1988),” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, October 29, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/our-mother-portable-mural-yolanda-m-lopezs-nuestra-madre-1981-1988/