The Construction of Paradise: Joiri Minaya’s Subversion of Colonial Encounters within Caribbean Tourism

Paradise, as a myth and a metaphor, has been associated with the Caribbean archipelago since Columbus described the region as a “terrestrial paradise” in 1498 during one of his voyages.1 Since then, the concept of paradise permeates tourism in the Caribbean—an industry situated within colonial racial capitalism, defined by Cedric Robisnon as the dominant form of capitalist development where race is not merely a factor but a fundamental component of the system.2 Multidisciplinary artist Joiri Minaya’s work examines Caribbean complexities around the region’s dark history of colonialism and slavery, and how these histories continue through different facets of tourism. In this essay, I discuss two artworks: #dominicanwomengooglesearch (2016), a sculptural collage exploration of body parts and tropical print suspended in movement within the gallery, and Containers #7 (2020), a photographic documentation of a constrained subject wearing a tropical print bodysuit in various poses. I argue Joiri Minaya’s work dismantles the tourist’s gaze by challenging colonial, racial, and sexual power dynamics that continue to be replicated in the tourism industry, along with its preoccupation in selling the concept of paradise.

The Colonial History of Paradise

The colonization and domination of the landscape, and its population, has always been at the center of the colonial project of the archipelago and I suggest, evoked in Minaya’s art. In her examination of the historical associations between Caribbean and paradise, sociologist Mimi Sheller identifies four historical eras in the development of the concept of paradise, which crafted these colonial associations within the region.3 In the first era (sixteenth and seventeenth centuries), the construction of paradise in the Caribbean was characterized by Western religion and colonial imaginaries forcefully converting Indigenous populations to Christianity which promised to bring paradise through “salvation.” The taxonomy and classification of tropical flora and fauna also became a priority during colonization in order to document and report their new tropical possessions back to Europe. The second era (eighteenth century) was then characterized by the enslavement and genocide of Black and Indigenous peoples through the plantation economy. Later, the third era (nineteenth century) was characterized by Romanticism and Imperial expansion in the Caribbean when imperialist ideas of natural explorations and the domination of nature began to gain more popularity in Europe and North America. For Sheller, the fourth era (twentieth and twenty-first centuries) is characterized by capitalism and its desire to sell paradise to the tourist or consumer. Despite the significant historical shifts throughout these centuries, contemporary tourism campaigns still deeply cling to the idea of paradise and its colonial roots within the regional context when selling the Caribbean, and are at the center of Minaya’s critiques.

Tropical flora and fauna are a consistent motif in Minaya’s visual practice and allude to the colonial history of paradise. In fact, curator Marina Reyes Franco, in the exhibition catalogue for Resisting Paradise, mentions how Minaya’s patterns reference scientific drawings used to classify and facilitate the study of colonial, tropical possessions.4 The use of tropical fabrics by the artist is an intentional historical thread back to this colonial practice illustration, however in her characteristic subversive methodology, Minaya often uses these patterns to evoke “opacity.” As defined by philosopher Édouard Glissant, opacity is the right to refusal, the agency over the subject’s right to be legible, or not, under the outsider’s gaze.5 Minaya’s work integrates tropical patterns as camouflage and uses opacity as a visual strategy of resistance, where the represented subject holds power over how and when their image is being represented.

#dominicanwomengooglesearch: Pixelation as a Form of Opacity

The work #dominicanwomengooglesearch (2016) is an installation of life-size, pixelated cutout images of different Black and Brown women’s body parts, with tropical patterns painted on their reverse side, kinetically suspended from the gallery ceiling. The work emerges from a series of collages and postcards Minaya began in 2015, for which she searched “Dominican women” on Google and integrated the representations of women she found into her collages. Following this Google research exercise, the artist noticed these images offered a very narrow representation of “Dominicanness” as they only generated thin people, attractive by Western beauty standards, and with a large focus on flesh and the body.

In her research, Minaya also found a pattern of “bodies in tropical spaces that are imagined as related to nature.” 6 Within colonial structures, equating local populations with nature is a form of violence and dehumanization as these structures are concerned with dominating both humans and landscapes. Moreover, the flesh holds significant importance in the tourism industry’s interest in consumption of the Caribbean based on colonial, racial and sexist systems of power. However, in #dominicanwomengooglesearch, the suspended body parts, moving by the force of gravity, are all highly pixelated, blurring their definitive features, in what Minaya characterizes as an exercise of visual opacity. The viewer is then denied complete access to the figure’s body, subverting expectations of who then holds the power in tourism’s embodied encounter, or what Shiller describes as a form of “consumer cannibalism” of “Caribbean difference.”7 While the tourism industry’s construct of paradise, as it relates to the Caribbean, promotes the idea of the docile local at the disposal of the visitor, Minaya uses opacity for these figures to subvert the colonial, racial, and sexual hierarchies imposed on the region through colonialism and enslavement.

Containers #7: Camouflage and Re-touring the Tourist’s Gaze

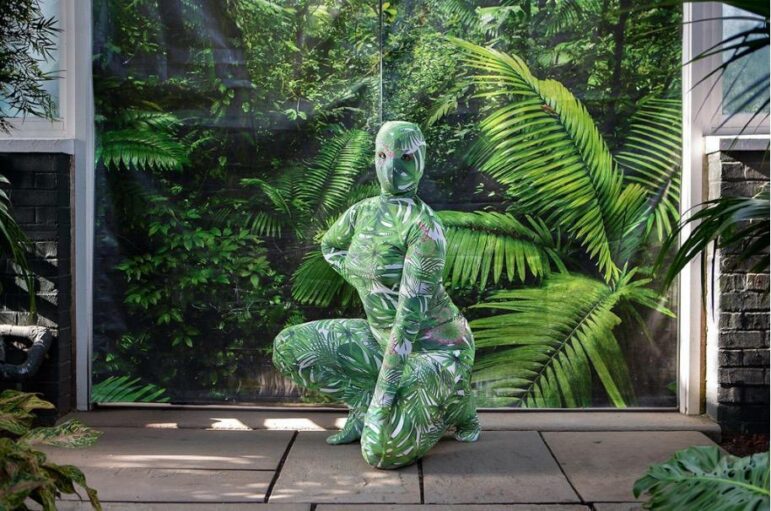

Similarly, in her multidisciplinary series, Containers (2015-2020), Minaya presents figures wearing a bodysuit made of tropical patterned fabric. Their bodies are fully covered except for their eyes, as they pose and contort themselves in spaces that are seemingly natural. The figure’s pose is determined by the construction of the bodysuit and forces the subject to position themselves in specific poses. In her google search of Dominicanness Minaya observed the represented women online were either in sexy poses’ or reclined as an odalisque.8

In Container #7, a figure poses in front of a digitally printed photograph of a tropical environment, while the figure is framed by cement and brick walls, windows, and piping inside a greenhouse. The figure wears a full bodysuit, created by the artist, using patterned fabric depicting green and white tropical flora.9 Minaya sees the use of camouflage as a form of visual opacity, where the figure wearing the tropical motif pattern as camouflage reserves the right to remain hidden or to show themselves.10 Moreover, the performance aspect alludes to how locals, especially those that work in the tourism industry, are expected to constantly recreate paradise for the viewer/tourist at their own expense, such as the psychological weight of servitude or the exhaustion of constantly performing for others. Oftentimes, as is the case here, Minaya is the subject performing within the Containers series, framing an added layer of opacity, as the artist ‘performs’ for the viewer.

In Container #7, the subject looks back at the viewer through the only opening in the bodysuit, gazing back and reclaiming their agency. From an art historical perspective, the returned gaze (the subject of an artwork looking back at the viewer) is deeply symbolic and has been used as a tool of subversion since the nineteenth th century. In the context of tourism, Mimi Sheller observes that “embodied encounters leave a space for contesting the gaze, deflecting the gaze, returning the gaze, appropriating the gaze, and destabilizing the power of the gaze.”11 Minaya creates such embodied encounters through her art that challenge the tourist’s gaze.

This series also challenges questions of labor in relation to the tourism industry. “I’m here to entertain you, but only during my shift” is the last phrase narrated in the video documentation of Minaya’s Containers Series, and a phrase the artist has repeated in previous works such as Siboney (2014), where Minaya paints a tropical pattern on oil paint, then, once its finished, spreads her body across the wall, still wet to the touch, and smearing the tropical motif painting.12 Labor is at the center of this statement, as it establishes the parameters of the embodied encounters between locals and tourists, one of a certain expectation of servitude, echoing back to histories of colonialism and enslavement, and places the worker at a disbalance. At the end of the video, Minaya removes the tropical-motif spandex, revealing her identity, and highlighting the role of performance, and choosing when to perform within the artwork. They do not owe the visitor their body, they are there to entertain them, but only “during their shift.”

Conclusion

Tourism, and its reliance on the trope of paradise as a descriptor for the tropics, has shaped how we view and “market” the Caribbean in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In her practice, Minaya exposes the tropes of paradise to understand how colonial racial capitalism developed and continues impacting social and power relations in the Caribbean region. Both #dominicanwomengooglesearch and Containers #7 challenge and confront these colonial power dynamics by contesting the sexualization and servitude of Black and Brown bodies, and by using opacity as a form of visual sovereignty in embodied encounters enacted through tourism.

Endnotes

- Christopher Columbus, “Friday, 21st of February,” in Journal of the First Voyage of Christopher Columbus (during his first voyage, 1492-93), and Documents Relating to the Voyages of John Cabot and Gaspar Corte Real, edited and translated by Clements R. Markham (London: Hakluyt Society, 1893), 184. ↩︎

- Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of The Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 1983). ↩︎

- Mimi Sheller, “Nature, landscape, and the tropical tourist gaze,” in Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies (Routledge, 2003), 36-38. ↩︎

- Marina Reyes Franco, Resisting Paradise, exhibition catalog (Fonderie Darling, 2019). ↩︎

- Édouard Glissant, “For Opacity,” in Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (University of Michigan Press, 1997), 189. ↩︎

- Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), “Joiri Minaya | PAFA – Visiting Artist Program,” YouTube, February 17, 2020, visiting artist lecture, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZgXoilWm0wQ. ↩︎

- Mimi Sheller, “Eating others: Of cannibals, vampires, and zombies,” in Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies (Routledge, 2003), 145. ↩︎

- The artist began “making the relationship between this containment and this pre-imagined identity, and how it’s performed through poses that are repeated.” Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), “Joiri Minaya | PAFA – Visiting Artist Program.” ↩︎

- Krista Thompson expands on the complex legacy of the Caribbean picturesque through what she terms ‘tropicalization.’ She defines it as “the complex visual systems through which the islands were imaged for tourist consumption and the social and political implications of these representations on actual physical space on the islands and their inhabitants.” The popularization of what is considered tropical fabric originates from European botanical illustration from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and was later adapted for aloha shirts in the twentieth century; these prints were used as a way to categorize and control nature for foreign consumption. See Krista Thompson, An Eye for the Tropics: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque (Duke University Press, 2006), 5. ↩︎

- Here, Minaya defines Opacity through Glissant’s theory of “the right to Opacity,” where those who chose to remain opaque are in control of how they are perceived, thus giving them visual sovereignty in embodied encounters enacted through tourism; Joiri Minaya, “Joiri Minaya | PAFA – Visiting Artist Program,” virtual lecture, February 17, 2020, by Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), YouTube, 1:15:12, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZgXoilWm0wQ. ↩︎

- Mimi Sheller, “The Tourist’s Gaze,” in Citizenship from Below: Erotic Agency and Caribbean Freedom (Duke University Press, 2012), 212. ↩︎

- Joiri Minaya, Containers (2015–2020). Photo, video, performance. Documentation video trailer, https://vimeo.com/289093085. ↩︎

Cite as: Bettina Pérez Martínez, “The Construction of Paradise: Joiri Minaya’s Subversion of Colonial Encounters within Caribbean Tourism,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, January 13, 2026, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/the-construction-of-paradisejoiri-minayas-subversion-of-colonial-encounters-within-caribbean-tourism/.

Bettina Pérez Martínez is a Puerto Rican curator, art historian, and researcher living and working in Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang (Montréal). Her research and publications focus on Caribbean identity, diaspora, decolonial studies, Puerto Rican history and its current politics, and the politics of ecology and climate change in the Caribbean region.