On the Maternal Archetype: Transformation and Transmutation in Delilah Montoya’s “La Malinche” and “La Guadalupana”

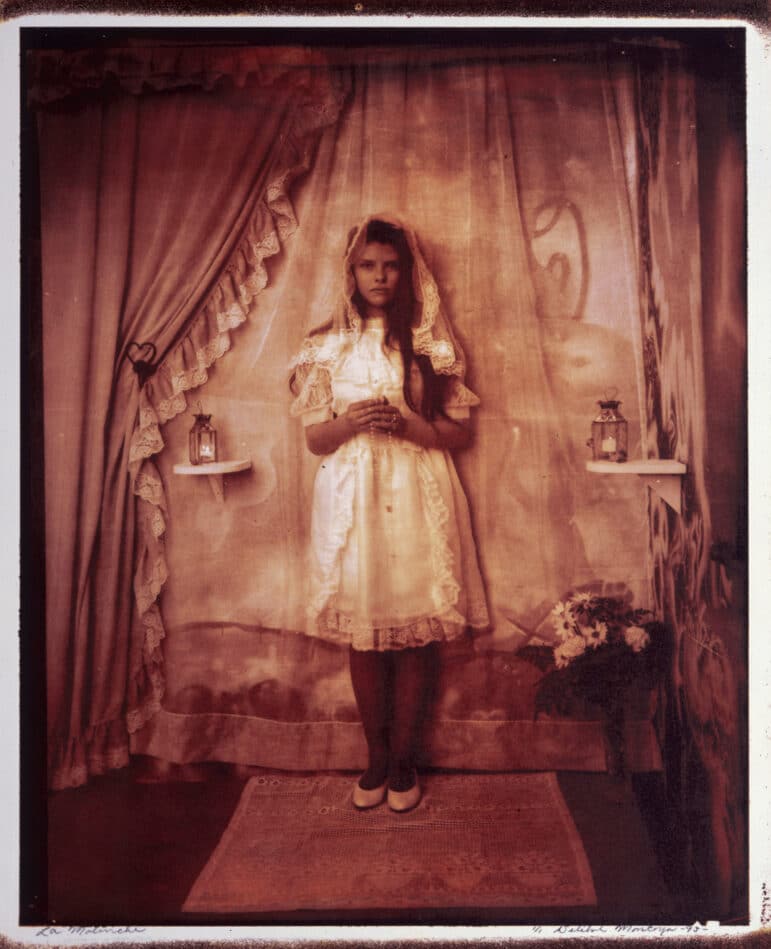

A young girl gazes outward from the portrait, eyes fixated on the unknown viewer. Her white dress—suitable for a first communion—reaches to her knees; a pair of white flats adorn her stocking-covered feet. The dress is trimmed with elegant lace, the neckline modestly high and the shoulders firmly covered with lace sleeves. Crowned with a lace-trimmed veil, holding a rosary in her bare hands, the young girl stands in an altar-like setting, ready to give herself to God or to Church, accordingly. And yet, our perception of the figure drastically changes when we regard her titular description: La Malinche.

Since the inception of the Chicano Movement in the 1960s and 70s, and in part as a means of feminist resistance against its patriarchal tendencies early in its history, Chicana feminist thinkers have been intellectualizing and writing about the archetypal las tres madres—the Virgin of Guadalupe, Malinche, and La Llorona—by way of theorizing the connections between their cultural, political, and religious implications. As literary scholar Christina Herrera explains: “The mother archetype in various forms pervades Mexican folklore, songs, and other oral traditions, making the maternal image very common and familiar to a majority of Mexicanos/as and Chicanos/as.”1 These figures have a wide reach that touches daily life in all aspects. Two of many works by Delilah Montoya that deal with las tres madres, La Malinche (1993) and La Guadalupana (1998), signify a long-standing commitment to engage with what the artist terms “Malcriada Aesthetics,” relating to the women who “just will not conform to the social norm.”2 In these works, Montoya challenges conventional narratives surrounding the figures of La Malinche and Our Lady of Guadalupe, representing their respective maternal archetypal figures and transforming or transmuting them simultaneously.

Malinche, one of the malcriadas Montoya refers to, has a story with a distinct historical precedence, though her image and sentiment have largely become relegated to the imaginary and the mythical. Known by many names—Malintzin, Malinalli, Doña Marina, among others—Malinche was a Nahua woman who acted as interpreter, intermediary, and eventually consort of the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. Seen as a traitor to her people and to the greater American hemisphere, Malinche is a rejected mother, a “bad” mother, understood to be inferior and rife with negative connotations. Also referred to as la chingada, or “the fucked one,” her status as the mythological mother of the mestizo delegates her to an important role in the Latinx imaginary.3

Montoya’s image of La Malinche, a small-scale photograph, offers a novel approach to a complicated figure. The photograph emphasizes the idea of Malinche as the first Indigenous Christian of the Americas while simultaneously reminding us of how young she was when she was sold into slavery and then taken by Hernán Cortés.4 Further, her facial expression suggests that she is not complacent in her role, a stern look about her that makes her appear powerful, even in the midst of being taken. The image garners a darker tone, however, when we consider the way it is staged after the brothel portraits of E. J. Bellocq (1873-1949).5 Bellocq was a U.S. photographer in the early twentieth century, famed for his portraits of sex workers in Storyville, the legal red-light district of New Orleans. As Montoya herself stated: “I began to understand how consequential she was, and how complicated she is … I wanted to point to her sensuality … I remember … some of the images of these women … just standing there, staring at him … I was thinking of Bellocq.”6 The images she refers to, published posthumously, portray the women of Storyville as models of beauty, elaborately staged wearing suggestive dress, amidst luxurious draped fabrics and bouquets of flowers. Montoya staged her composition in a similar manner. A girl, purposely chosen at that in-between stage of child and adult, stands alone in a centrally composed image, flowers set in a vase on the floor next to her and fabrics draped behind her. Like Bellocq’s black-and-white photographs, Montoya’s image is similarly monochromatic, having a sepia-toned, vintage quality to it. The image transforms into something more sinister as we consider the connection to Bellocq, connoting an innocence being stripped away through the conflation of young girl and sex work.7 This reframes our understanding of the figure, allowing us to see Malinche as a young woman forced into her role, rather than the willing traitor she is often painted to be.

Montoya has described that her own introduction to the figure of Malinche was through her mother, offering an anecdote about her unwillingness to be a traitorous “Malinche” to her fellow seamstress coworkers by translating for the overseer of the company. “We understood who Malinche was,” Montoya explained. 8 This archetypal figure is one that hardly requires an explanation, and yet Montoya’s vision reinscribes her humanity back onto her body, conjuring the question: do we truly understand? Meaning for these types of figures can shift depending on the context, and grand icons such as Malinche can operate as complicated, multilayered figures that move beyond their surface-level representations.

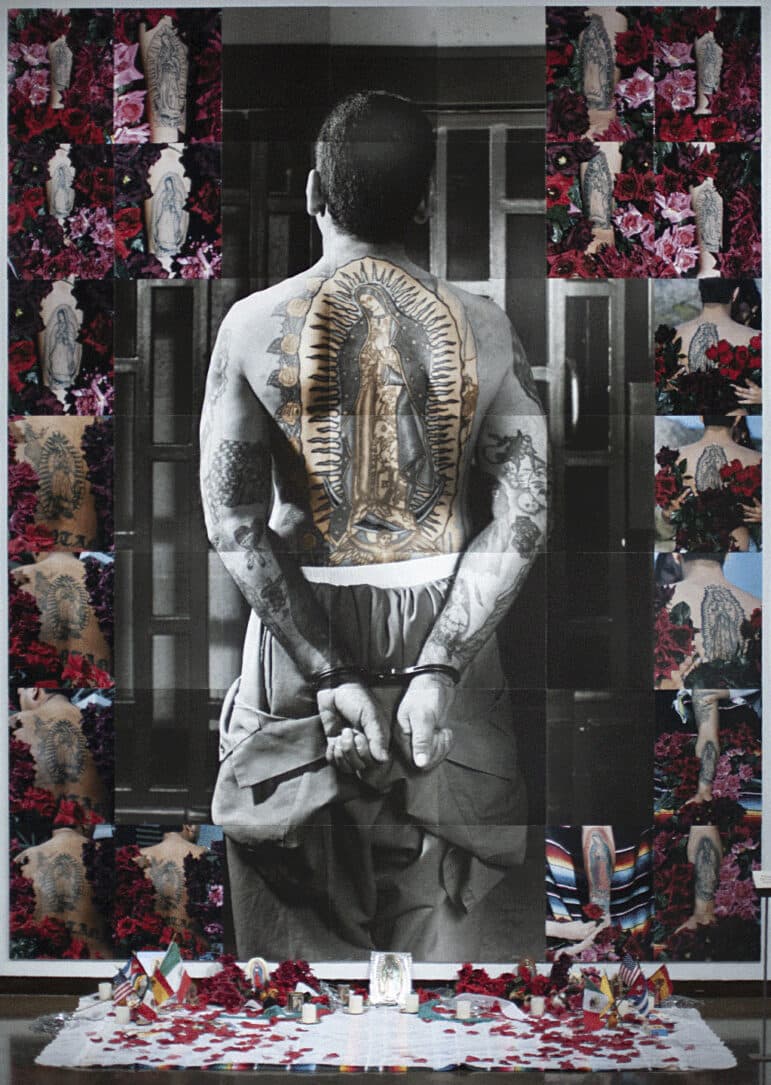

As a foil to Malinche’s traitorous background, Montoya’s 12 ½-foot mixed-media photo mural installation La Guadalupana highlights the “good mother” archetype, featuring an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe tattooed on the back of a Chicano veterano—Felix Martínez, who was being held in prison and awaiting trial for a drive-by shooting.9 Our Lady is the model of perfection that every woman is culturally expected to strive to attain. This “good mother” holds religious and cultural value within Catholicism and is often held as not only the ideal but the standard for mothers in their communities. Her image becomes the source of a martyr complex that urges women to focus on the “welfare of the family, the community, and the tribe [as] more important than the welfare of the individual.”10

The two main subjects that Montoya pictures here are striking in their conceptual difference. The first subject is Montoya’s model, a prisoner in the Albuquerque Detention Center, handcuffed with his arms behind his back, who stands facing away from the viewer toward iron bars. The second subject is the large prison tattoo of the sacred Our Lady of Guadalupe image covering Martínez’s back. The tattoo is one of two hand-colorized portions of the image, the second being the floral-esque border of the image, made up of Guadalupan tattoos on other men. Interested particularly in transmutation—the transformation from one state to another—Montoya plays with the idea of a lesser medium (prison tattoos) being transformed into one that is higher (a sacred image).11 Through the idea of transmutation, Montoya points out that there was, and will be, always the possibility for change, including for Martínez.12

Like the back-and-forth of La Malinche’s innocent/traitor dichotomy, this icon of the Virgin similarly modulates: if the icon is inherently good, what would happen if we were to venerate this image tattooed onto the back of someone who society deems “bad”? Perhaps, her presence on the back of a veterano makes this version of Our Lady of Guadalupe a malcriada, much like Malinche. This Guadalupan icon transforms from rote sacred imagery into something more complex, a figure of discomfort with whom, perhaps, we can better relate.

The original image of the Virgin, having appeared on a peasant’s tilma (cloak), was transformed into a sacred object. Montoya similarly performs an act of transformation, depicting the Virgin as she exists on a prisoner’s back. This image ultimately liberates Our Lady from the confines of the tilma on which her original image rests, elevating her to a new status that is fluid and peripatetic. She transforms into something more akin to the average person, just as La Malinche changes from traitor to innocent. As Stephanie Lewthwaite explains: “Montoya compels us to look again at popular . . . icons that suffer from misrepresentation, . . . whose struggles and sacrifices make them equally worthy of inclusion in her alternative Chicano/a pantheon.”13 In this way, Montoya’s figures supersede their archetypal origins, transforming into figures that offer a complexity that makes them appear more like human beings and less like mythological figures. With each new icon, Montoya reframes our understanding of these archetypes, rewriting them and elevating them as multifaceted figures beyond their individual roles in the popular imaginary. This, as she notes, is a central tenet of her practice in the late-nineties, casting her photographs as a conduit for transmutation.14

- Cristina Herrera, Contemporary Chicana Literature: (Re)Writing the Maternal Script (Cambria Press, 2014), 46.

↩︎ - Delilah Montoya, “Artist’s Statement: Malcriada Aesthetics/Bad Girl Realities,” Chicana/Latina Studies 15, no. 2 (Spring 2016): 10–16.

↩︎ - The term mestizo comes from the Latin word mixticius, meaning “mixed,” referring to the mixing of Indigenous and Spanish descent. It evolved as a term during the Spanish Empire and was used as both an ethnic category and as a legal designation. The mestizo was historically relegated to a lesser role than someone of full Spanish descent and became just one of a complex array of many assigned social castes based on ancestry called castas. See Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico (Yale University Press, 2004); and Magali Marie Carrera, Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings, (University of Texas Press, 2003). ↩︎

- Victoria I. Lyall, Terecita Romo, and Matthew H. Robb, “Introduction,” in Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche (Denver Art Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2022), 6. ↩︎

- Delilah Montoya, interview with the author, February 9, 2025. ↩︎

- Montoya, interview, February 9, 2025. ↩︎

- Montoya, interview, February 9, 2025. ↩︎

- Montoya, interview, February 9, 2025. ↩︎

- A veterano is an older long-time inmate and gang member who usually holds distinct influence on the younger members of Chicano gang life.

↩︎ - Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza: The Critical Edition (Aunt Lute Books, 2021), 40.

↩︎ - Montoya, interview, February 9, 2025. ↩︎

- Montoya, interview, February 9, 2025. ↩︎

- Stephanie Lewthwaite, “Revising the Archive: Documentary Portraiture in the Photography of Delilah Montoya,” in The Routledge Companion to Latina/o Popular Culture (Routledge, 2016), 227. ↩︎

- Montoya, interview, February 9, 2025. ↩︎

Emma Oslé holds a PhD in Art History from Rutgers University and is the 2024-2025 Terra Foundation for American Art Predoctoral Fellow and Big Ten Academic Alliance Smithsonian Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Her research provides an entryway to conceptualizing Latinx art through the central role of family.

Cite this essay: Emma Oslé, “On the Maternal Archetype: Transformation and Transmutation in Delilah Montoya’s La Malinche and La Guadalupana,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, October 29, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/on-the-maternal-archetype-transformation-and-transmutation-in-delilah-montoyas-la-malinche-and-la-guadalupana/