Memories of the Skin: The Work of Carlos Martiel

… I would say to this land whose loam is part of my flesh:

“I have wandered for a long time, and I am coming back

to the deserted hideousness of your sores.”1

Aimé Césaire

Thinking about the American continent means delving into social configurations where the land cannot be separated from everything that inhabits and happens upon it. The memory of our bodies and our practices—either native or those brought from Africa—functions as testimony, narrating across different times a plural history of millions of people uprooted from their gods, their land, their habits and their very lives, who have been taught to behave like flunkeys, as the Antillean thinker Aimé Césaire points out about the heavy weight of colonialism on the subjugated body.2 Colonialism’s inescapable web is also inscribed in the work and skin of artist Carlos Martiel.

For Martiel, exposing the repercussions of coloniality is essential. Through his own body, he responds to the dynamics that have shaped his life, one that, like the Caribbean itself, becomes a battleground for the vindication of Black existence, resisting the systematic erasure imposed on enslaved and oppressed peoples, an erasure that has been justified by dehumanization and violence, both in Latin America and the Global North. Martiel confronts this struggle through performance by making himself present, unavoidable, disrupting the static visual languages historically imposed on racialized bodies, embodying the figure of the enslaved who, with physical pain, faces the weight of the fist that oppresses him, inscribing onto his skin a reflection of this collective reality.

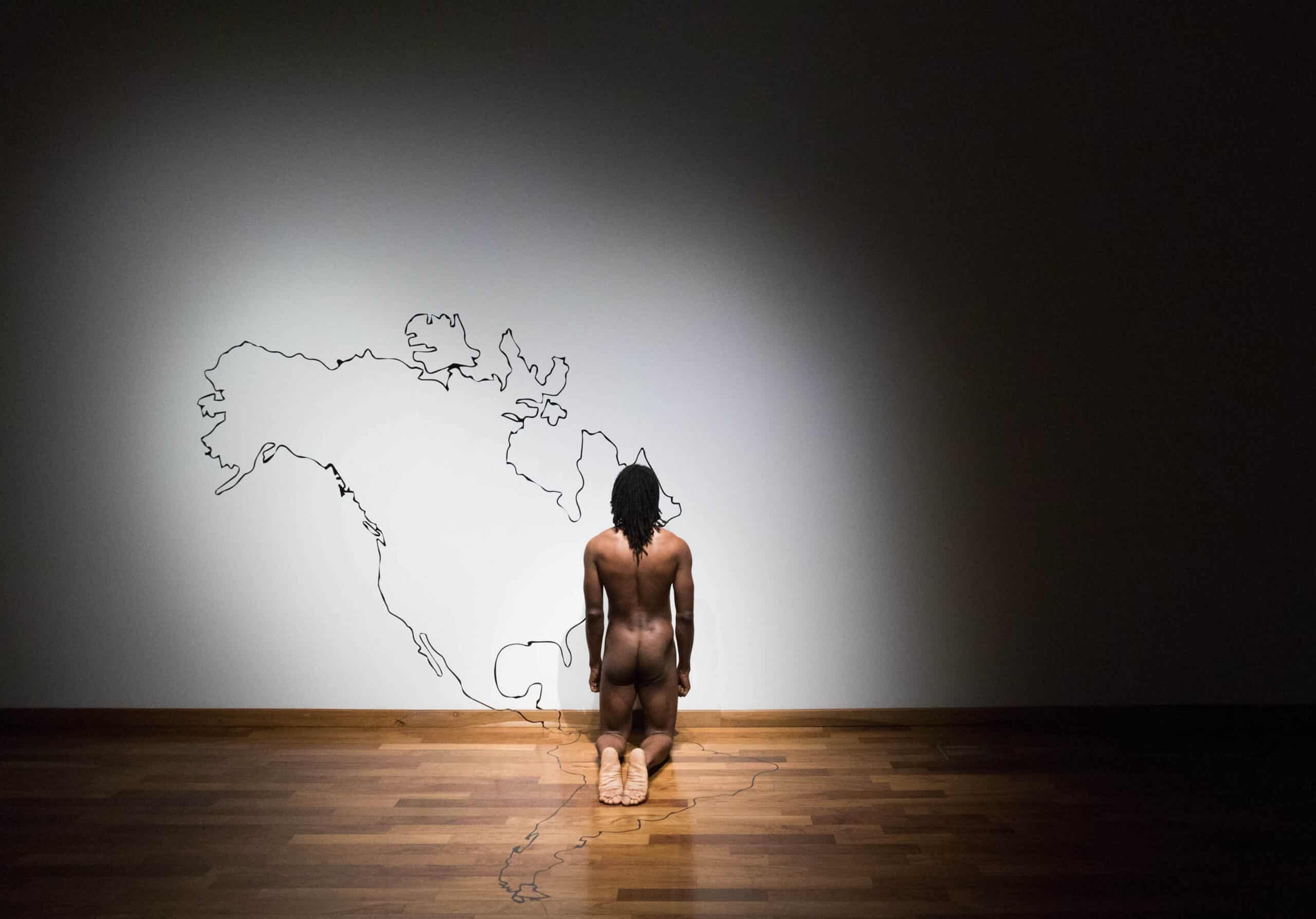

In the work Encomienda (2018), the silhouette of the American continent is traced onto the wall and floor, divided into two regions, north and south, resisting its reading as a unified whole. Before it, Martiel kneels naked over the southern region, witnessing with composure the division that both imprisons and makes him present, defying the notion of invisibility—that which lacks political agency and dwells in the margins of what does not exist. This struggle is explored by Frank B. Wilderson III in Afropessimism, where he reflects on Black being—and its diaspora—as a non-place, a space without redemption in contrast to a humanity that recognizes itself as such. 3 Here, however, Martiel’s physical presence turns his body into the central axis of this geography, making it tangible. Strategically, he positions himself as the being that has been denied and thus rendered unknown: “the geographic unknown, the corporeal indigenous/black unknown,” that Katherine McKittrick describes in relation to mapping the uninhabitable within a geography that the West must comprehend in order to dominate.4 In this work, the Black body directly becomes a visual record, bearing witness to our multiple histories. It becomes part of the South as a timeless possibility of existence—oscillating between what is acknowledged and what is meant to be erased, between what is known and what is ignored—only legible through the artist’s vulnerability. He presents himself as a scar, reminding us of the resilience of the flesh.

Maya Kaqchikel researcher Aura Cumes describes the fracture between North and South—between the subject and their territory—as a colonial and capitalist strategy that “has sought to destroy plurality, or to hierarchize it and establish a hegemony of the world of the One [a westernized singular subject] over the plural.”5 By constructing the Western world by isolating the Other, the West strips them of humanity, forcing them to disconnect from their community, nature, and environment, thus positioning itself as the center of everything and, ultimately, as part of nothing. Martiel’s work problematizes and destabilizes that center and that isolation, denouncing the reality of many Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples through his flesh, pointing to a social structure that not only imposed a racial and patriarchal hierarchy but also radically transformed the way life unfolds through epistemologies of domination.6 By centering itself, the West cornered—through violence and punishment—the Indigenous and Black subjects, subordinating their lives to the colonies that thrived on their sweat and blood.

Martiel asserts that Encomienda precisely refers to the idea of the body entrusted to forced labor, where he, as an Afro-descendant, embodies an existence shaped by the configuration of power on this continent.7 From this perspective, his artistic creation as a subjugated subject connects with the reality of other individuals who occupy a similar historical position. With this gesture, Martiel challenges the colonial world, the world of the One that Cumes points to, the power of the state over its oppressed subjects. Martiel claims a collective tenacity, emerging unbreakable—from the loam that is also his flesh—with a steadfast gaze toward the construction of a North that denies multiple existences. His mere contemplative presence becomes a reminder of the active struggles for freedom from this vast Global South that links us, illustrating our plural resistances, transforming his pain—and what crosses through him—into a collective sorrow.

Similarly, in the work Fundamento (Basis) (2020), Martiel portrays the evolution of the repressive policies of the modern state. Here, the artist reflects on the repercussions endured by Black and Indigenous communities under the consolidation of new imperial regimes. In this performance, Martiel lies on the ground, bound hand and foot, captive beneath the American flag. His posture is disturbingly familiar, evoking images of torture and lynching that persist both in historical documents and in recent cases of police brutality, urging us, the spectators, to question the temporality of a seemingly overcome past or, conversely, whether Fundamento serves as a call to a present that demands our articulation and disobedience.

Regarding this work, Martiel highlights its direct connection to South Body (2019), in which he lies on the ground with his shoulder pierced by a small pole holding the American flag. Both pieces function as an archive over which the violated body asserts its authority, sharing its vision of the historical and systematic violence inflicted upon Black individuals, violence that spans different temporalities of resistance: that of the enslaved African brought to the Americas and that of the hybrid Black subject, alienated by imperialism.

In this way, these works—along with others in which the artist employs imperialist symbols from nations that maintain colonial relationships—link what has been to what is through the memory of a body always in tension, a body that shows us that blackness is not passive, but rather becomes aware of its difference as memory, solidarity and revolt.8 Here, its corporeity turns as a living manifestation of a present in constant conflict with history, confronting narratives that have historically sought to erase us.

Therefore, a Black man, bound and looking toward the present, is not merely a denunciation of a violent past and its ongoing repercussions. Nor is it simply about finding him prostrated before our geography, redefined by the West. Rather, these gestures become a lesson about the world we inhabit today, one in which our convictions are reflected and can be felt moving through every muscle of the body. It is the uncomfortable friction of colonialism and imperialism, from which our bodies long to break free, understanding that we are all entwined in a plural history.

This is the power of Martiel’s performance: to embody the existence of Black humanity and make it visible; to stand in solidarity with the struggles of Indigenous peoples; and to express deep concern for forcibly displaced communities, for those facing genocide and war. His body, he asserts, is not only Black, not only migrant—validated or denied by one or multiple nations—but rather a convergence of realities seeking to expose, through the vulnerability of skin, crimes against humanity.9 A reciprocal feeling arises when witnessing Martiel’s work, where our collective memory lifts its gaze, glimpsing the possibility of a shared freedom.

I would come to this land of mine and I would say to it:

“Embrace me without fear . . .

And if all I can do is speak, it is for you I shall speak.”10

Aimé Césaire

Endnotes

- Aimé Césaire, Notebook of a Return to the Native Land (Wesleyan University Press, 2021), 17. ↩︎

- Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham (Monthly Review Press, 2000), 43. ↩︎

- See Frank B. Wilderson III, Afropessimism (Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2020). ↩︎

- Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Duke University Press, 2006), 128. ↩︎

- See Aura Cumes, “No somos sujetos culturales, somos sujetos políticos,” TUJAAL.ORG, Septemember 23, 2019, https://tujaal.org/aura-cumes-no-somos-sujetos-culturales-somos-sujetos-politicos/. ↩︎

- See Yasnaya Elena A. Gil, “Entrevista con Aura Cumes: la dualidad complementaria y el Popol vuj,” Revista de la Universidad de México, April 2021, https://www.revistadelauniversidad.mx/articles/8c6a441d-7b8a-4db5-a62f-98c71d32ae92/entrevista-con-aura-cumes-la-dualidad-complementaria-y-el-popol-vuj. ↩︎

- Carlos Martiel, conversation with the author, December 2024. ↩︎

- See Aimé Césaire, “Discurso sobre la negritud. Negritud, etnicidad y culturas afroamericanas,” trans. Beñat Baltza Álvarez, in Discurso sobre el colonialismo (Ediciones Akal, 2006), 87. ↩︎

- Martiel, conversation with the author, December 2024. ↩︎

- Césaire, Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, 17. ↩︎

B’alam Waykan García (b. 1991) is a multidisciplinary Kaqchikel artist focused on Indigenous identity practices. Through performance and oral tradition, his work seeks to expose structures of domination. He holds an MFA from the University of Illinois, Chicago, and was supported by the Fulbright Program.

Cite this essay: B’alam García, “Memories of the Skin: The Work of Carlos Martiel,” in X as Intersection: Writing on Latinx Art, August 4, 2025, accessed [DATE], https://uslaf.org/essay/memories-of-the-skin-the-work-of-carlos-martiel/